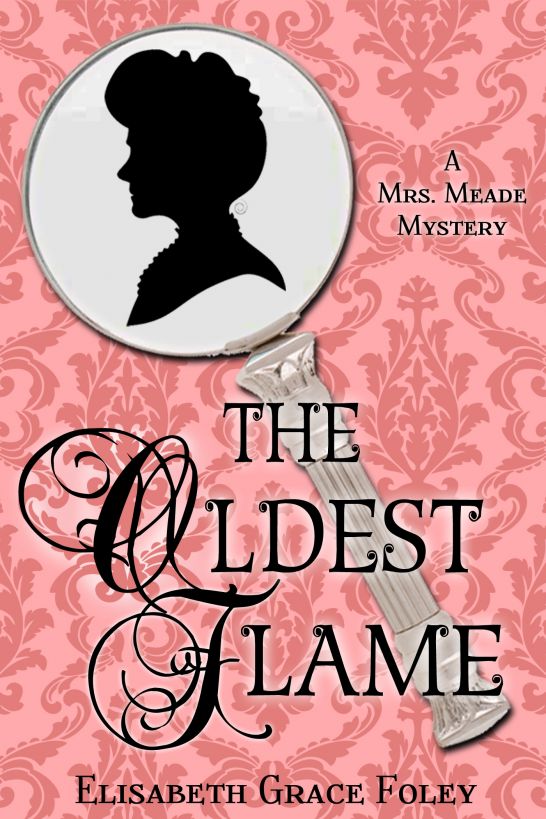

The Oldest Flame

Authors: Elisabeth Grace Foley

Tags: #mystery, #woman sleuth, #colorado, #cozy mystery, #edwardian, #novelette, #historical mystery, #short mystery, #lady detective

The Oldest Flame: A Mrs. Meade Mystery

By Elisabeth Grace Foley

Cover design by Historical Editorial

Silhouette artwork by Casey Koester

Photo credits

Victorian wallpaper © milalala| Vectorstock.com

Magnifying glass © mvp | Fotolia.com

Smashwords Edition

This e-book is licensed for your personal enjoyment

only. This e-book may not be re-sold or given away to other people.

If you would like to share this book with another person, please

purchase an additional copy for each person. If you’re reading this

book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use

only, then please return to Smashwords.com and purchase your own

copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Copyright © 2014 Elisabeth Grace Foley

Table of Contents

A man would incur any danger for a woman…would

even die for her! But if this were done simply

with the object of winning her, where was that real

love of

which sacrifice of self on behalf of another is the

truest proof?

~ Anthony Trollope

Mrs. Meade gazed with much pleasure and

contentment over the view from the garden bench where she sat.

Below the well-kept gardens of the other houses strung out down the

slope of the hill, a silvery glimpse of the river in the valley

twinkled bright in the afternoon sun, with a lovely vista of wooded

hills rising beyond it. Here in the garden, the air of the summer

afternoon was soft and peaceful, with bees humming among the

flowers and now and then the sweet piercing song of a bird from the

trees high overhead.

Mrs. Meade looked around the garden again,

her admiration mixed with something like marveling. The latter

expression was accompanied by a touch of motherly fondness as she

turned to look at her companion, who was leaning against the tree

which cast its shade over the bench.

“How you have grown, Mark!” she said. “The

last time I saw you, you were just a rambunctious schoolboy. And

now look at the fine young college man you’ve grown into.”

Mark Lansbury grinned with just a touch of

self-consciousness. He was a dark, good-looking boy of nineteen,

tall and athletic, with a pair of arresting, expressive brown eyes.

With Mrs. Meade, whom he had always regarded in the light of a

favorite aunt, he was always at his ease, and did not find it

necessary to observe the dignity that had become rather more

important to him since attaining the aforementioned collegiate

status.

“Everything seems to have moved very quickly

for your family these past few years,” said Mrs. Meade. “Your

father’s promotion—this beautiful new house—and then you off to

college. I’ve missed seeing all of you, these years you’ve been so

busy. I was so very happy when I received your mother’s invitation

last month, to find she had remembered me.”

“She could never forget you!” said Mark

warmly. “None of us could. Mother was always thinking about you,

even when things were busiest. I’ve heard her speak of you a

hundred times.”

“Well, as things have turned out, I’m glad

she chose this summer to invite me, since the Greys are here. It’s

been so good to see them again too.”

Mark did not answer this. He picked at the

smooth bark of the tree, looking down at the grass at Mrs. Meade’s

feet, the animation of a moment before gone from his face. Mrs.

Meade observed him quietly for a moment, and then, in a voice and

manner so light and natural it could never have aroused any

suspicion of ulterior motives, entered on an entirely new

subject.

“How do you like college?” she said. “Your

father told me you were doing very well, but you’ve hardly said a

word about it since I’ve been here. Was your first year a good

one?”

“Oh, yes, it was fine,” said Mark, shying a

broken bit of bark at the ground. “But to tell you the truth, I

haven’t been thinking much about college lately.”

“There’s something else on your mind, then?”

said Mrs. Meade, who had already divined as much.

“Some

one

else, anyway,” Mark mumbled,

looking down again with a little color in his face.

“My dear boy, don’t tell me you’ve tumbled

into a love-affair already!”

“Oh, I didn’t tumble,” said Mark, looking

over at her with an uneasy smile, as if he already half regretted

sharing his secret. “It’s been coming on steadily enough.” He

paused. “It’s Rose, of course. Could you even think it was anyone

else?”

There was something different in his voice as

he spoke these last words, a subtle ring of feeling that made Mrs.

Meade look up at him with closer attention. His restless eyes met

hers for an instant. Yes, he had grown up a good deal, she thought.

Sensitive, earnest, impatient, ardent—all those qualities of youth

were there in abundance, but somewhere along the way a door had

opened to the capacity for a deeper feeling, one likely to throw

all those very qualities into turmoil.

“Rose,” she said thoughtfully. Mark nodded,

watching her as if hoping to gain some sort of encouragement from

her response.

“I knew you were always good friends when you

were children, but I didn’t know you felt that way about her.”

“Well, I do now,” said Mark. “I’m in love

with her—miserably in love with her, Mrs. Meade, but she doesn’t

care whether I’m alive or dead.”

Mrs. Meade forbid herself to smile. She had

long since learned to balance her sense of humor with her

expression of sympathy, and Mark Lansbury was intensely in

earnest.

“That seems rather unlikely,” she said. “Does

Rose know yet how you feel?”

“She knows I’m in love with her. I’ve told

her so. But she doesn’t take me seriously. She thinks it’s just an

infatuation and I’ll get over it.” He swung round so his back was

against the trunk of the tree. “I used to think, at first, that

maybe…”

A wistful look came over his face for a few

seconds, but then it vanished and his mouth set bitterly. He thrust

his hands deep in his pockets. “But she’s never been the same since

she met that Steven Emery. She’d believe anything he told her,

whether it was the truth or not.”

Mrs. Meade had been introduced to Steven

Emery for the first time the evening before, and she understood the

complication to Mark’s problem.

“Who is Mr. Emery exactly? I thought at first

that he was a friend of your father’s.”

“No. The Greys met him somehow in Denver last

winter, and he’s been hanging around them ever since. Mr. Grey

introduced him to Dad when Dad was in the city on business. That’s

why he got included in the invitation when Mother asked the Greys

down here, I think. Dad’s trying to get him to invest in the new

railroad project he wants to put through, because Emery’s supposed

to have money. But I don’t think he’s biting. He’s too busy

entertaining Rose.”

“Is that why he came down here, do you

think?” said Mrs. Meade.

Mark gave a disheartened shrug. “I don’t know

whether he has any serious intentions, or if he’s just amusing

himself. He’s a lot older than her, you know. But I

am

serious. How can I make Rose see that?”

“Have you tried poetry?” suggested the

practical Mrs. Meade.

“I wrote a lot,” said Mark, “and then tore it

up. Rose would only laugh at it. But if it was Steven Emery or

someone else like him writing her sonnets, she’d think it grand.

It’s all a matter of perception—the way she sees me,” he added, as

if he felt it necessary to explain for Mrs. Meade’s benefit.

Mrs. Meade did not entirely succeed in hiding

her smile this time, since she had spent a good portion of this

conversation trying to adjust her own perception of the parties in

question. The image that still came most vividly to her mind was

one she had seen from her window some years before, of an

eight-year-old Rose and eleven-year-old Mark constructing a river

and dam in the mud of a ditch below the railway embankment. But

that was before prosperity, in the form of railroads, had descended

upon both families—and girlhood upon Rose.

“Nothing I can say will make any difference

to Rose,” Mark was saying. “My trouble is that there’s nothing I

can

do

. I’ve got no way of showing her what I’m made

of.”

“No, there are few dragons to slay in our

everyday life,” said Mrs. Meade thoughtfully. “But do you know,

I’ve always thought the girls who would take a man on his

dragon-slaying merits rather short-sighted. There are plenty of men

who can rise to the occasion when something extraordinary happens,

but what about the little things—the common things? Those are what

will matter most in the rest of their life together.”

“I don’t know,” said Mark. “I’ve always

thought the crisis shows the essence of a man’s character—the trial

by fire, so to speak. How he answers to that gives you the clue to

everything else about him.”

“How do you think you would be in a crisis?”

inquired Mrs. Meade, gravely, but with a genial twinkle in her

eye.

Mark reddened a little, but he answered, “I’d

like

to think I’d come out well…but I don’t see how I’ll

ever have the opportunity.”

“Don’t give up, Mark,” said Mrs. Meade,

putting her hand out to him with a warm, affectionate manner that

acted upon him so far as to bring a somewhat forlorn smile to his

face. “Rose is young yet—she may not know just what it is she

wants. But don’t waste all your time waiting for your grand chance.

Just be ‘faithful in that which is least’—and perhaps one day

you’ll find your chance is come.”

“Do you really think I could make my own

chance…that way?” said Mark, sounding a little doubtful, but with a

somewhat vacant look in his eyes, as if he was turning over an idea

in his mind.

“Perhaps you could. Who knows?” said Mrs.

Meade, smiling again.

“Yes,” said Mark, “who knows.”

* * *

When Mrs. Meade came through the open French

window into the sunny lower hall, a woman was just coming down the

staircase opposite. She was dressed for the evening, in white with

a pale peach-colored sash, a very simply cut dress that suited her

tall, spare style of beauty in such a way that Mrs. Meade

inadvertently paused to admire the effect. She had been introduced

to Eloisa Parrish on the preceding evening and had been similarly

struck by her appearance, but had had little or no success in

forming an acquaintance with her. Miss Parrish was a handsome young

woman of twenty-seven or twenty-eight, with a certain austerity

about her finely molded features and an almost haughty lift to her

narrow chin. She had remained silent and aloof through most of the

evening in the drawing-room, seemingly unmoved by any kind of

pleasantry or any topic of conversation.

She paused for half an instant on the lowest

stair as her eyes fell on Mrs. Meade, as if she had not expected to

encounter anyone here or did not particularly want to. Mrs. Meade,

however, did not see this movement, or perhaps chose not to see

it.

“Oh, good afternoon, Miss Parrish,” she said

pleasantly. “I was just on my way up to dress for dinner. It has

been so fine out that I’ve spent most of the day outdoors. Have you

seen much of the garden?”

“No,” said Miss Parrish with the barest of

polite smiles, a slight curve of the lips that did not mean much.

“No, I have hardly been out of my room today.”

“I hope you are not feeling ill?” said Mrs.

Meade. Her direct, yet considerate eyes took stock of the younger

woman’s face. “You look a little pale, if I may say so.”

A door opened somewhere in the direction of

the drawing-room and voices drifted out, and over them rose the

sound of a young girl’s happy laugh. Neither woman’s eyes wavered,

but an almost contemptuous expression passed across Miss Parrish’s

face.

She lifted her chin slightly, though not,

Mrs. Meade thought, so much with defiance as with the air of one

who would conceal some emotion. “I must have had a headache, I

suppose,” said Miss Parrish in a cool, ironical voice. “At least

that is what I must say if I’m asked. That is what we all say,

isn’t it, to hide a more embarrassing ailment—the desire for

solitude.”

Without another word she moved past Mrs.

Meade and went out through the French window onto the terrace. Mrs.

Meade looked after her with a slightly perplexed expression, but at

nearly the same moment she heard footsteps behind her and turned

back as Mrs. Lansbury came into the hall.

Mrs. Lansbury had entered in time to see Miss

Parrish disappear through the window, and to observe the expression

on Mrs. Meade’s face, and there was understanding in the smile

which she exchanged with her friend.