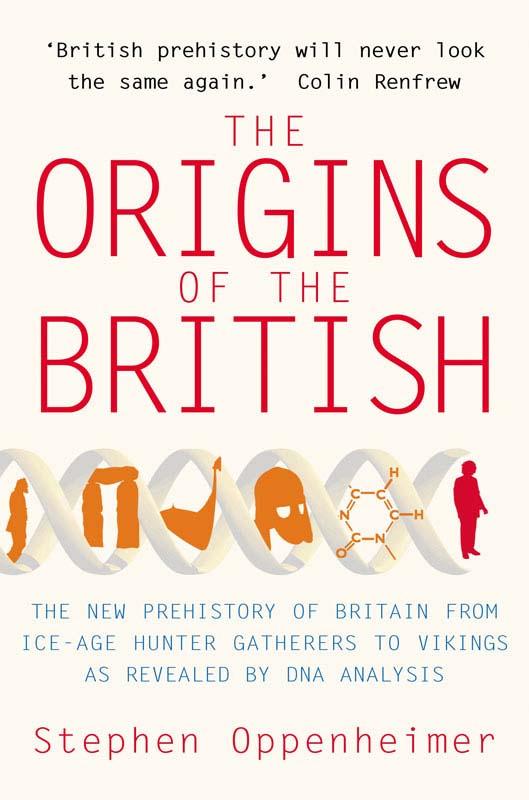

The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain

Read The Origins of the British: The New Prehistory of Britain Online

Authors: Oppenheimer

‘Stephen Oppenheimer is the supreme genetic detective fishing for evidence in the gene-pools of history.’ Professor Clive Gamble, University of London

‘He upends some of the most deeply rooted notions of where the British people come from, and does so in a clear, painstaking and detailed way. The result is both fascinating and unexpected.’

Geographical

‘The historians’ account is wrong in almost every detail. In Dr Oppenheimer’s reconstruction of events, the principal ancestors of today’s British and Irish populations arrived from Spain about 16,000 years ago.’

New York Times

‘

Particularly illuminating … The author carefully lays out the genetic data that show how three-quarters of Britishness dates to the repopulation after the northern ice sheets last retreated, and takes us through a fascinating investigation of what this means for some cherished notions of Britishness.’

Nature

‘Comes to clear and provocative conclusions, offering an intellectual feast to anyone interested in British identity.’

Financial Times

‘Oppenheimer’s fascinating thesis helps to answer one of the most vexing questions of dark-age British history: why is there so little trace of Celtic culture in England and in the English language?’

Prospect

‘The most heavyweight of recent books devoted to British origins. A fascinating, if at times controversial, read.’

Current Archaeology

By the same author

By the same authorThe Drowned Continent of Southeast Asia

The Peopling of the World

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

First published in the UK by Constable,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2006

Copyright © Stephen Oppenheimer, 2006, 2007

The right of Stephen Oppenheimer to be identified as the

author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition

that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold,

hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover

other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition

including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

is available from the British Library

ISBN 978–1–84529–482–3

eISBN 978-1-78033-767-8

Printed and bound in the EU

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

of

David Oppenheimer

classicist, composer, clinician

and

father

C

ONTENTS

Part 1 The Celtic myth: wrong myth, real people

1 ‘Celt’: what it means today, and who were the classical historians referring to?

Part 2 Colonization of the British Isles before the Roman invasion

Introduction: Can language dating tell us when the Celts arrived?

4 Ultimate hunters and gatherers: the Mesolithic

5 Invasion of the farmers: the Neolithic and the Metal Age

6 Who spread Indo-European languages?

Part 3 Men from the north: Angles, Saxons, Vikings and Normans

7 What languages were spoken in England before the ‘Anglo-Saxon invasions’?

8 Was the first English nearer Norse or Low Saxon?

9 Were there Saxons in England before the Romans left?

10 Old English perceptions of ethnicity: Scandinavian or Low Saxon?

11 English continuity or replacement?

Appendix B: Our maternal ancestors: an overview

of the European gene tree

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I started thinking about the peopling of the British Isles in terms of sources, numbers and timing of founders over five years ago, when I heard Barry Cunliffe talk about the ancient unity of cultures along the Atlantic coast. I was attending an excellent series of talks put on by Linacre College, Oxford. These talks were later published under the title

The Peopling of Britain: The Shaping of a Human Landscape

(edited by Paul Slack and Ryk Ward), but I picked up ideas from other fascinating lectures in the series by archaeologists Heinrich Härke, Paul Mellars and Clive Gamble and the demographer Richard Smith.

Much of

Origins

results from new analysis that I have carried out on existing genetic data; parts of the story are retold from other people’s published work and synthesized from the relevant disciplines, with a focus on genetic heritage. The bibliography measures my attempt to cover different points of view

and the perspectives of the different disciplines – the study of human history, archaeology, genetics, language, climate and sea level. For instance, as with my last book, I have found Jonathan Adams’ palaeo-environmental website invaluable for maps. There are several geneticists whose laboratory work, with colleagues, over the past few years has added enormously to the genetic database for the British Isles and neighbouring countries, and should be singled out. They include Cristian Capelli, Jim Wilson, Michael Weale, Mark Thomas, Martin Richards, Zoë Rosser, Siiri Rootsi, Kristiina Tambets, Luísa Pereira, María Brion, Antonio Torroni, Peter Forster and Chris Tyler-Smith, among many others. As a rule (and there are few exceptions), geneticists generously make their raw data available in the public domain on publication of their analyses. This has allowed me (and others) to pool similar genetic data, reanalyse and make inter-regional comparisons.

But I have not done this in isolation. I have had much assistance and advice from many of the people mentioned above. Orcadian geneticist Jim Wilson has been enormously helpful in pointing me towards appropriate Y-chromosome datasets, making his own data available, giving critical advice, warning of pitfalls and suggesting alternative methods of analysis, even how to get the best out of Excel, not to mention e-mailing me relevant publications.

Colleagues Martin Richards, Peter Forster and Vincent Macaulay have given me much of their time on the phone and insights into their own work in progress. Martin’s publications, with colleagues, on the impact of the Neolithic on Europe from the perspective of mitochondrial DNA form a benchmark in the use of the phylogeographic method in European prehistory.

Peter Forster and I share several perspectives on English genetic ancestry, and we even came up with the same linguistic questions by different routes. I have also benefited from discussion and comparing methods of analysis with Bill Amos. Other geneticists who have given me their time in discussion include Cristian Capelli, Siiri Rootsi, Kristiina Tambets, Mark Thomas, Michael Weale and Antonio Torroni.

I have also received constructive criticism and advice from archaeologists, including Barry Cunliffe, who kindly read and commented on the entire book, Nick Barton, who concentrated on the Late Glacial and Early Holocene sections, and Helena Hamerow, who read the Anglo-Saxon parts. Others who generously gave me their time and help include Jill Cook, who provided the photo-micrograph of the Creswell horse engraving, Simon James, Beatrice Clayre and Graeme Barker.

I am very grateful for time and constructive criticism given me by linguists, in particular Patrick Sims-Williams, who was a great source of advice and references, including many he had written himself. He also read through and commented on the language sections. Other linguists – April McMahon, John Penney, Katherine Forsyth and Wendy Davies – gave their time and advice, as did members of the English Place-name List on the Internet. I also received very useful material and insight from non-linguists working on language trees and networks, including Peter Forster, Quentin Atkinson and Geoff Nicholls.