The Other Anzacs (33 page)

Eighty kilometres north of the Somme River, Harry Moffitt and his comrades settled into camp in peaceful farming country near Fromelles. The village was in German hands and close to the front. Notable for a slight rise to the west known as Aubers Ridge, the area was unusual, as the water table and destroyed irrigation had forced both sides to build up their trenches rather than dig down. The thick sandbag walls had the appearance of medieval battlements facing off on either side of no man’s land. A feature of the line was a bulge known as the Sugarloaf salient. In mid-1916 the Sugarloaf was a strategically important German stronghold, an elevated concrete fortress bristling with machine guns.

Today, the Sugarloaf seems barely a blip on the horizon as you trudge towards it along the edges of freshly ploughed fields. But this bucolic scene is deceptive. Nearby is the cemetery of VC Corner. There are no individual headstones here, just one mass grave containing the unidentifiable remains of 410 Diggers. At the back of the cemetery, on a perimeter wall, are the names of a further 1298 men of the 5th Division who died in the area and have no known grave. And not far away, in a field known as Pheasant Wood, it is now suspected that around 170 more Diggers were buried by the Germans in a mass grave.

Harry Moffitt’s 53rd Battalion was part of the 14th Brigade. Along with battalions making up the 8th and 15th Brigades, it formed the AIF 5th Division, established only a few months earlier from a nucleus of Gallipoli troops. The 5th Division was the last AIF division to sail from Egypt in June 1916. The Australians thought they were going to a ‘nursery’ area on the Flanders front, where the fighting was light. They would have time to adjust and acclimatise to vastly different conditions. Instead, they found themselves preparing for immediate action on the Western Front.

The British Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig, feared that the Germans might move troops from Flanders to reinforce their Somme forces. He wanted to keep the Germans in place. All he needed was to show his forces and keep the Germans guessing about his intention. They would not move men south if they feared an attack. For days the Allied generals bickered about the best plan. Some were in favour of trying to fool the Germans with a feint attack; others wanted a pure artillery barrage; infantry operations were proposed, planned, cancelled and reinstated. The object was to take the Sugarloaf, and about a kilometre of German reserve line that was presumed to run parallel to the front.

The 15th Brigade leader, Brigadier General H.E. ‘Pompey’ Elliott, was profoundly concerned. As his biographer Ross McMullin has noted, Elliott thought the operation inadvisable for a host of reasons: preparations would be rushed, the artillery was inexperienced, and parts of no man’s land were too wide—up to 400 yards in places. The distance was crucial: for troops carrying a full twenty-five-kilogram pack, the maximum for an infantry charge to be effective was half that distance. Elliott’s men would also have to advance opposite the formidable German strongpoint at the Sugarloaf.

With Elliott’s misgivings growing, he met Major H.C.L. Howard, a visiting staff officer from Haig’s headquarters. As McMullin describes it, Elliott took Howard forward not just to the front line but beyond, to a post in no man’s land that afforded a good view of the Sugarloaf. Elliott showed Howard his plans and draft orders and asked for his frank assessment. ‘Visibly moved, Howard predicted the attack would prove “a bloody holocaust”. Elliott urged him to go back to Sir Douglas Haig and say so. Howard promised he would. Whatever Howard may have said to Haig, the attack was delayed but not cancelled. The attack was fixed for 19 July.’

1

Despite the clear shortcomings in planning and preparation, an AIF artillery bombardment in preparation for the attack went ahead on the morning of the 19th. Because of inadequate equipment, training and insufficient time for the artillery to become familiar with the battlefield, the bombardment failed to cut the barbed wire or destroy the machine-gun emplacements at the Sugarloaf. The 5th Division, under the command of Irish-born Australian Major-General James Whiteside McCay, was given the task of taking the German trenches. The division was to link up with a depleted British territorial division, the 61st, which, although short of manpower and training, was responsible for the Sugarloaf. This was some task, as there was no cover across no man’s land and the bulge was protected by a host of German machine-gun nests capable of enfilading, or firing, on the British and Australian troops from the side.

At 5:45 p.m. on 19 July, in the first AIF action in France, the infantry climbed over the sandbagged parapets and attacked across the shell-holed and featureless meadow, notable only for a muddy, metre-deep stream, the Laies, that ran through no man’s land and impeded progress. The broad daylight of midsummer meant the Germans could see the troops coming. Having observed the build-up from balloons and from the higher ground at Aubers Ridge, they were well prepared for the assault. There have also been suggestions that there were spies and collaborators at work: the clock in the town tower moved faster during relief changeovers, white horses were moved into certain paddocks, different-coloured washing was hung out. According to one story, the Germans held up a sign saying, ‘Aussies come on, you were meant to be here yesterday.’

As the infantry attacked across a narrow section of no man’s land, the Germans unleashed a deadly machine-gun barrage. The AIF 15th Brigade and the British 184th Brigade were decimated. The 15th had the widest section to cover, about 400 yards. Compounding the difficulty was the uncut barbed wire. The German machine guns were aimed between the men’s waists and knees to ensure their upper bodies were hit as they fell. As the German guns rattled away, the men fell in their hundreds, the atmosphere alive with the lethal sound of bullets

zip, zip zipping

into their bodies. As one survivor later described the scene, ‘the air was thick with bullets, swishing in a flat, crisscrossed lattice of death. Hundreds were mown down in the flicker of an eyelid, like great rows of teeth knocked from a comb . . . Men were cut in two by streams of bullets [that] swept like whirling knives . . . It was the charge of the Light Brigade once more, but more terrible, more hopeless.’

2

The 15th Brigade lost eighty per cent of its men and the battlefield was awash with blood.

The goal of Harry Moffitt’s 14th Brigade was to reach the German line, about 250 yards away. Despite the Sugarloaf machine guns, somehow men from the brigade managed to storm the German front line within thirty minutes, and to hold the gains overnight. But the gains came at a dreadful cost in officers as well as men, which meant they soon needed not just more troops but someone to give orders. After eleven hours these remnants of the brigade were all that was left of the disastrous plan. They were still in the German trenches when a counterattack began, leaving them in a desperate position. Orders were given to retreat. The commander of the 14th, Colonel Harold Pope, boasted later that his was the only brigade that had to be ordered back.

By 8 a.m. on 20 July 1916, the battle—also known as the Battle of Fleurbaix—was over. A 59th Battalion corporal, Hugh Knyvett, wrote, ‘If you had gathered the stock of a thousand butcher-shops, cut it into small pieces and strewn it about, it would give you a faint conception of the shambles those trenches were.’

3

According to the official Australian war historian, Charles Bean, the sight of the Australian trenches that morning, ‘packed with wounded and dying, was unexampled in the history of the AIF’.

The four trenches which had been dug into no man’s land in the sectors of the several brigades were full of helpless men. Especially in front of the 15th Brigade, around the Laies, the wounded could be seen everywhere raising their limbs in pain or turning hopelessly, hour after hour, from one side to the other.

4

The wounded lay in no man’s land, ‘tortured and helpless’ among the dead, ‘within a stone’s throw of safety but apparently without hope of it’.

In his book

Don’t Forget Me, Cobber

, Robin Corfield wrote:

At this time on no-man’s land there were probably in the vicinity of 1000 men so disabled by their wounds that they had no alternative but shelter in shell-holes or ditches, or in some cases, in the water of the river Laies. They would call out for help or in pain. Their hand would be seen above the edges of the hole in which they sheltered, waving to gain attention. Others silently bled to death in the grass or the river. Those alive were of course in great need of water as well as bandages.

5

By midnight on the night of the 19th, it was clear that a major medical tragedy was unfolding. There were so many wounded to clear from the battlefield that the stretcher bearers became exhausted by the grim task of carrying them to the regimental aid posts and then to the advanced dressing stations. From there, the wounded were taken to the two main dressing stations, where they were evacuated at a rate of two a minute. Ambulances took them to No. 2 Australian Casualty Clearing Station at Trois Arbres. At 10 o’clock on the evening of the assault, the first ambulance convoys began to arrive. They kept on coming until the next morning, when the station was ordered to close until it could be cleared of the wounded. A nearby British casualty clearing station at Bailleul opened its wards to cope with the overflow.

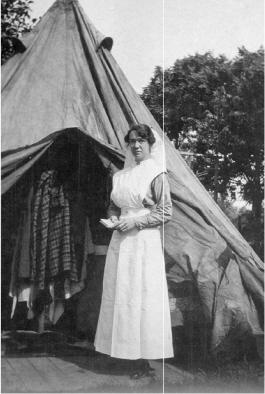

No. 2 clearing station had more than 800 patients, some in the theatre but most in the care of the sisters, who were all flat out doing dressings and giving anti-tetanus inoculations. At 5 a.m. on the 20th, the duty nurses were given four hours off. They slept, then went back on duty to clear patients out to the base hospitals on two ambulance trains. The men were gone by nine that night. Next day came another ambulance convoy. The operating theatre just kept going.

The scene was worse at the British casualty clearing station. Nurses there described the situation as ‘a butcher’s shop’ as they dealt with joints and limbs mutilated by shellfire. Many men had not been evacuated quickly enough. Sometimes, nurses found the wounds crawling with maggots where flies had settled on an undressed wound in the field. Helpfully, the maggots ate up the putrefying tissue and helped keep the wound clean. There were no miracle drugs to combat infection in 1916, just disinfectant to keep the wound clean and, with luck, keep sepsis at bay so the wound could heal. Sometimes, if a wound was stitched up too early, there would be a ‘flare’ of infection later. Gangrene could set in and kill a patient within twenty-four hours.

The wards were like battlefields, with wrecks of men in every bed and stretcher. Those with abdominal wounds were the worst. Fewer than two in 100 survived. A huge number had bullet wounds, and if the projectile had gone straight through them without hitting bone, they were mostly all right. The soldiers with head wounds were almost all hopeless cases. There was little the nurses could do for them but keep them comfortable and help them die decently. Mercifully, there was plenty of morphine.

The 5th Australian Division suffered 5533 casualties, including 1917 killed in action. It was the most costly and tragic twenty-four-hour period in Australian history. The casualty list represented an extraordinary fifty per cent of all troops engaged. Normally in the AIF the ratio of ‘wounded’ and ‘died of wounds’ to ‘killed in action’ was approximately four to one. In the 15th Brigade at Fromelles, it was less than three to two. The increase was a consequence of men being shot to death as they lay wounded in no man’s land, or dying there for want of assistance. The casualties decimated the 5th Division for months to come.

Historians have ascribed the main responsibility for the defeat to the British Corps commander, Lieutenant General Sir Richard Haking, who argued for the feint attack. Someone who knew him was Lieutenant Colonel Phillip Game, who served in a division under Haking and was later to become famous as the New South Wales Governor who sacked Premier Jack Lang. To Game, Haking was a ‘vindictive bully’ and a ‘bad man’ who could not be trusted ‘halfway across the road’.

6