the Other Wes Moore (2010) (24 page)

Read the Other Wes Moore (2010) Online

Authors: Wes Moore

Standing under the NASDAQ screen in the heart of Times Square. I rang the closing bell at the New York Stock Exchange with members of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America.

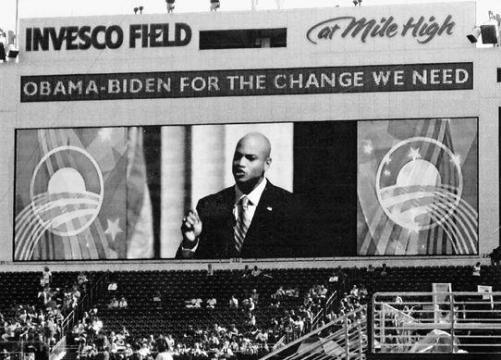

Speaking in front of tens of thousands at INVESCO Field in Denver. I spoke just hours before Barack Obama accepted the Democratic nomination for president and forty-five years to the day after Dr. Martin Luther King's "I have a dream" speech.

Even after getting shot twice in the chest and once in the head, Sergeant Prothero stumbled off and ran about ten feet, finally falling in the green bushes that surrounded the jewelry store. For the next minutes, he fought a losing battle for his life. The two getaway cars had long since screeched out of the parking lot.

Crime in Baltimore and its suburbs had spiraled out of control, particularly in the city proper. Baltimore City was now averaging over three hundred murders a year, making it one of the per capita deadliest cities in America. Police officers were consistently trying to solve gun crimes, drug-related crimes, domestic abuse crimes, and robberies. But this case was different, more personal to the cops assigned to it. Not only did it take place outside Baltimore City, in the county, an area where vicious murders were less common, but this shooting involved one of their own. All hands would be on deck to make sure that the perpetrators were brought to justice.

The first major lead in the case came a day after the shooting. One of the suspects called a notorious drug dealer to offer him a chance to buy some stolen watches. The drug dealer had an authorized wiretap on his phone and, as a result, the police got a search warrant and went to the house where the call originated. When they found one of the stolen watches under a seat cushion, they suspected they had their man. He later confessed to being in on the robbery but denied that he had pulled the trigger. Through his interviews, the police identified the other three men, where they lived, and more details about the crime.

A day later, another member of the crew was captured. He also confessed to being at the scene but said that he was not the one who pulled the trigger. In fact, he was later quoted as saying, "I was actually unarmed. I was just told I could make fifty thousand dollars to break some glass." This wasn't the first trip through the criminal justice system for either of them. Both men, in their early twenties, had long criminal records that included drug charges, handgun violations, and assault charges. One of them had been charged a year before with two counts of first-degree murder for separate shootings in West Baltimore.

Mary was riveted as she listened to the reporter's dry voice. It was an audacious crime, a troubling sign of the violence that felt like it was closing in on her no matter how far she moved away from the center of the city. Her phone started to ring. Again she ignored it. Then the reporter described the final two suspects. The reporter warned those watching that they should be assumed to be "armed and very dangerous." Mary's large-screen television was now filled with photos of these suspects. Her heart broke when she saw Tony's and Wes's faces staring back at her.

Midnight passed, and one day turned to the next. Mary could not sleep. She felt terrible about the death of the police officer. She prayed her sons were not responsible. As she lay in bed, she realized that, no matter what the outcome, all of their lives had changed forever. Mary knew it was just a matter of time before she would become the target of questioning. She had not spoken to Wes or Tony for days, but after hearing the news, she wanted to speak to them just as much as she was sure the police did.

At 4:00 A.M., Mary heard a loud banging on her metal front door. "Police! Open this door!"

She threw on a blue robe, yelling that she was on her way. She could tell from the increasingly frantic banging that the police were seconds away from coming in--with or without an invitation. She cracked open the door, her right eye peering out to see who was waiting. She looked past the stocky man in plain clothes and saw ten--maybe more--cops lined up behind him. A few wore uniforms. More were wearing plain clothes. All were tense. Some had their weapons raised, some had them holstered, their hands ready to snap the guns loose at a moment's notice. Only a thin, hollow metal door stood between her and them.

The plainclothesman in front of her flashed a badge, showed a search warrant, and brusquely asked Mary for permission to enter. She took a step back and, as soon as she did, the door swung open and the officers flooded into her home.

With weapons drawn, teams split up and searched for Wes, Tony, or any evidence that they'd been there recently. One of the officers escorted Mary out of the house and sat her on the stairs outside. She hugged herself as the cold February air blew through her cotton bathrobe.

Before long an officer appeared before her and unleashed a barrage of sternly delivered questions. But Mary could only keep repeating the truth: she had no idea where the boys were and had not seen them in weeks.

"Did you know that both of your sons are on probation?"

"Yes, I did."

"Tony is supposed to be on home detention for a drug conviction, and Wesley is still on probation for drug charges from a few years ago--"

"I know what they were on probation for, Officer."

"If you knew where they were, would you tell us?"

Mary finally snapped at them. "Look, I just found out that my sons are wanted for killing a police officer. If I find anything out, I will tell you, and I will cooperate however I can, but right now I don't need to be questioned like I did something wrong."

The questions and searching of the house continued for the next hour. The jarring percussion of drawers being opened and closed, dressers being shifted around, and beds being flipped over rattled through the quiet night and shook Mary's nerves. Black, spit-shined police shoes with hard rubber soles cracked down on every inch of hardwood floor. Mary sat on the outdoor concrete steps with the officer standing over her, the two mirroring each other's despair and frustration.

The first rays of morning lit up the still deserted streets of Dundalk, Maryland, where Mary's new home was located, as the cops mounted up to leave her ransacked space. Every crevice had been inspected, every room had been searched, every secret presumably uncovered. The police departed with a threat: they would be back and would not leave her alone until they found Tony and Wes. To nobody's surprise, they were true to their word.

The search for the Moores had just begun.

Two days after that first early morning visit, Mary's niece, Nicey's daughter, was moments from walking down the aisle for her wedding. As a recording of "Here Comes the Bride" played over the loudspeaker in the Northeast Baltimore church, the rear doors opened and the veiled bride began her slow procession toward the altar. She walked alone down the aisle as the well-wishers in the pews stood and smiled. Tony was supposed to walk arm in arm with his cousin and give her away--her father had never been involved in her life. Her unescorted stroll down the aisle was a subtle reminder that the manhunt for two of Maryland's most wanted was still on, now in day five.

The family had been bombarded with interview requests, police questioning, and neighborhood stares. Both city and county police had been crisscrossing their jurisdictions, looking for any sign of Wes and Tony. The police conducted a raid of the Circle Terrace apartments in Lansdowne, where Tony lived. Acting on a tip, they combed the North Point neighborhood in Baltimore. A team of officers went by Wes's current address, on the 2700 block of Calvert Street in the city--on the outskirts of Johns Hopkins University, close enough that Wes could see and hear the construction slowly creeping in around him. The police plastered the neighborhood with wanted posters, advertising a sizable reward. In the evenings, a police chopper with searchlights flew over the Essex community, where Wes had lived a few years earlier.

The wedding was a reprieve for the family. This celebration was the first time in days that they could simply enjoy one another's company without the events of February seventh dominating the conversation. Today was supposed to be about joy and love.

Following the ceremony, the doors to the church opened to a clear and cool winter day. A hundred or so people slowly filed into the street. The snow that had fallen a few days earlier was now a dark slush shoveled against the sides of the road. All of the attendees loaded into their vehicles, and set off for the reception hall, ten minutes away. Each driver put on hazard lights as the slow convoy snaked its way to Southeast Baltimore.

Two of the vehicles, the ones carrying the eight members of the wedding party, decided to break from the pack and take a quick detour to a 7-Eleven on the Alameda, a main artery in Baltimore City. They wanted to grab a few sodas and some bags of chips before the reception, just in case it took a while for the food to show up after they arrived. A block away from the store, an unmarked police car pulled up behind the vehicles, red and blue lights flashing. The same car had been sitting outside the church, its occupants observing the celebratory congregants as they walked out. The wedding party pulled over.

Doors slammed, and three policemen leaped out of the car and walked up to the wedding party's vehicles. They forced all eight of the passengers from the vehicles and ordered them to sit on the curb of the traffic island that split Alameda. The men, wearing their white tuxedos, and the women, wearing silky silver, spaghetti-strapped dresses, complained about having to sit on the slushy curb in their wedding outfits. They were told that they would have to sit down or be arrested. And then one of the officers addressed the group.

"Y'all know there is a reward for Tony and Wes if you just tell us where they are. It's a lot of money. You sure you don't need that money? This would be much easier on you if you would just say where those two are."

The eight sat silently, shivering in their now soaked clothes, while the police continued to grill them. It had been more than thirty minutes since they were pulled over. No information had been collected, not a single idea about the whereabouts of Wes and Tony had been divulged. The wedding party simply sat on the ground, late for the reception and, by now, tremendously agitated. The police, circling the party, felt much the same way.

Finally, the officers ordered them back into their cars, but not before placing handcuffs on one of the drivers because he didn't have the proper registration for the rental car they were driving. The rest of the wedding party yelled at the officers as they placed their friend in the back of the cruiser. The arresting officer simply looked back at the group and said, "Enjoy the reception. I hope y'all remember where Tony Moore and Wes Moore are. Quickly."

Wes was walking down a street, a Philly cheesesteak in one hand and a new pair of blue jeans in the other. His brother was by his side. Thirty feet away--at the corner--he noticed a police cruiser. As he got closer, he noticed that the engine was running, and that the two cops inside were murmuring into their walkie-talkies. This was the same squad car Wes had noticed twice earlier in the day, in different parts of the city but always within fifty feet of where he and Tony stood. But no one had made a move for them, so Wes had chalked it up as simple coincidence. He and Tony continued to move through the crowded Germantown streets toward his uncle's house in North Philadelphia. The crime-ridden neighborhood was where Tony and Wes had escaped just days after the murder.

North Philadelphia reminded Wes of the Baltimore neighborhood he had just left. The check-cashing stores instead of banks, the rows of beauty salons, liquor stores, laundromats, funeral homes, and their graffiti-laced walls were the universal streetscape of poverty. The hood was the hood, no matter what city you were in. But just blocks away from their uncle's house, scattered evidence of gentrification--driven by the looming presence of Temple University--had started to manifest. Their uncle's block, where half of the homes sat abandoned and burnt out, represented what the neighborhood had become. Blocks away, where newly built mixed-income homes sat next to picturesque buildings like the gothic Church of the Advocate, built in 1887, was the direction the neighborhood wanted to go. But even that dynamic wasn't unique; the same thing was happening in Wes's neighborhood, where Hopkins was the driving force of change, aimed at improving the quality of life for students and faculty. Wes wondered where people like him were supposed to go once they'd been priced out of the old neighborhoods, once the land changed hands right under their feet.

When they got back to the house, Wes went upstairs to the room that housed the bunk bed he and Tony shared. Tupac's "Keep Ya Head Up" was on the radio, and Wes turned it up. It was one of his favorites, Pac's voice defiant over the melancholy chorus sampled from the Five Stairsteps--"Ooh, child, things are gonna get easier." Wes sat down on his bed and opened the plastic bag that held his cheesesteak. The grease leaked from the packaging, and the aroma of the Cheeze Whiz and grilled onions rose from a puncture in the aluminum foil.