The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (26 page)

Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

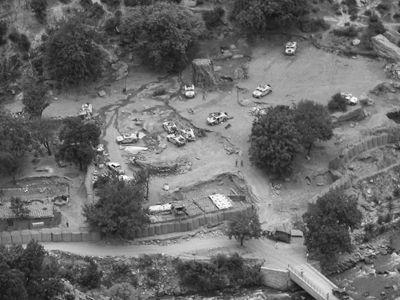

The construction and fortification of the base in Kamdesh had begun in earnest by the fall of 2006, but there was nothing troops could do about its position at the bottom of the Kamdesh Valley. In this photo, Staff Sergeant Lance Blind of 3rd Platoon, Able Troop, looks for enemy bodies after a firefight the night before.

(Photograph by Jeremiah Ridgeway)

Combat Outpost Kamdesh, fall 2006.

(Photo courtesy of Matthew Netzel)

Even before the weather turned dreadful, helicopter pilots were reluctant to make the journey to the Kamdesh PRT to bring supplies, spooked by the near miss involving Byers’s chopper. At Forward Operating Base Naray, therefore, Captain Pete Stambersky made other plans.

Stambersky commanded the forward support unit assigned to the area. Delta Company—attached to 3-71 Cav from the 710th Brigade’s Support Battalion—was comprised of about a hundred soldiers who worked as cooks, mechanics, welders, truck drivers, petroleum specialists, and logistics experts. To resupply the Kamdesh PRT, Stambersky and his Distribution Platoon leader, First Lieutenant David Heitner, packed five Afghan trucks and two Toyota pickups with needed items. The trucks, driven by locals and nicknamed jingle trucks for the sound made by the colorful decorative chains and pendants hanging from their bodies, were loaded with food, water, building materials, and generators. Because insurgent attacks along the road had been increasing—it seemed that virtually every convoy that passed was being assaulted—Howard told Stambersky to take along a reconnaissance platoon in trucks, which brought his total number of gun trucks from six to eleven. To Stambersky, the additional manpower and firepower were welcome, but they also felt ominous.

October 17, 2006, dawned on Nuristan with a clear sky and temperatures in the sixties. Stambersky instructed the drivers of the jingle trucks to take the rear: he didn’t trust them, and he knew that if they weren’t in back, it would be easy enough for any one of them to stop his jingle truck and block the Humvees from passing, thus setting the Americans up for an ambush. It was a decision that Michael Howard would later criticize, convinced as he was that their being in the rear made the already vulnerable jingle trucks even more so.

Slowly, steadily, the convoy moved north. Efforts to reconstruct the road notwithstanding, the terrain remained treacherous. And there was, as always, the enemy. The convoy passed through what was now being called Ambush Alley, where some MPs were already watching over the road. Just past the Gawardesh Bridge, Stambersky and his men stopped briefly to pay a local teacher for some work he had done on his school, then resumed their journey to the PRT, approaching the hamlet of Saret Koleh to their right.

Stambersky regularly carried a picture of Jesus in his front pocket; his father had been given the icon in 1948 for his First Communion. On his way to the Kamdesh

27

Valley, the captain patted his chest to assure himself that he had the picture.

It wasn’t there.

In the rear seat of Stambersky’s Humvee, his forward observer, excited about his impending R&R, couldn’t contain himself: “Just nine days till leave and I’ll be getting some ass!” he yelled. Stambersky and his driver both told the soldier to shut up—“You’re jinxing us,” Stambersky said.

As if on cue, RPGs just then began erupting on either side of the convoy, followed by small-arms fire. The vehicles kept pushing ahead. An RPG flew by Stambersky’s right window and struck a Humvee driven by some of the Barbarians, detonating the truck’s load of ammo. The Humvee burst into flames as the troops—finance guys, carrying a bag of petty cash for Able Troop—spilled out onto the ground and ran behind a rock.

Many vehicles were destroyed in the October 17, 2006, ambush on a convoy on its way to the new outpost.

(Photo courtesy of Pete Stambersky)

Stambersky looked at his gunner, whose .50-caliber machine gun was jamming. An RPG exploded to the left of them, rocking their Humvee and filling it with black plumes even as it continued driving. “Get on the SAW!” Stambersky ordered the gunner, referring to his M249 light machine gun. He then called to each surviving truck to check for casualties and damage. Everyone was okay, but since they couldn’t leave the burning truck behind, the convoy stopped, and the battle was joined. Stambersky’s forward observer informed the tactical operations center at Forward Operating Base Naray that the convoy was under attack, and the operations center then requested Apaches from Bagram, but the air support would surely take at least forty-five minutes to get there, and likely much longer. In the meantime, the jingle trucks—all in the back of the convoy, unprotected by and separate from the Americans—began exploding and catching on fire.

From the PRT, Gooding sent out a QRF—quick reaction force—to help Stambersky and his men as they returned fire. Meanwhile, Stambersky’s forward observer got on the radio and called for a B-1 bomber. B-1s were regularly dispatched from the U.S. base on the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean; they would fly around particular regions on shifts, waiting for calls such as this one.

When the QRF approached the ambush location from the Kamdesh PRT twenty minutes later, its members relayed the enemy’s coordinates to Stambersky, who shared the ten-digit grid with his forward observer, who gave it to the B-1 pilot.

“We need your initials,” the pilot said.

“P.S.,” Pete Stambersky said into the transmitter, “drop the bomb!”

A two-thousand-pounder fell.

Then another.

Now, at last, the Apaches got there; they provided cover while Stambersky and his men removed the shell of the burnt-out Humvee from the road so others could pass. In the process, the captain noticed the remains of a Soviet vehicle in the nearby river. For a split second, the metal skeleton reminded him of a couple of different American armored trucks: the V-100 Commando, the M1117 Guardian. Another war—or not.

Passing the QRF on its way, the convoy continued on to the Kamdesh PRT.

It was funny: everyone in Stambersky’s convoy had been dreading the trip to the now notoriously hard-to-get-to PRT, but that night it was home sweet home as the troops—many of whom had never had any previous contact with the enemy—shuffled around with expressions of relief and shock on their faces. No smiles, just a muted gratitude at being safe. Better to be here than out there. It was amazing that no one in the convoy had been killed that day.

Stambersky knew that such relief was momentary and illusory. The Kamdesh PRT was small and poorly situated. If you looked up, as he did now, all you could see was mountains until your neck was craned back and you could finally see sky. Tomorrow they would assess the damage. Not one of the jingle trucks had made it to Kamdesh; all had been destroyed and would have to be pushed into the river to clear the narrow road. The next day, when men from 3-71 Cav went to remove the remnants of the burning trucks—which had been bringing them what were to have become the first hot meals that many of them had had in months—they could smell charred steaks and chicken that had cooked in the conflagration from the attack.

When the base was being set up, any officer who referred to “Camp Kamdesh” or “Combat Outpost Kamdesh” would quickly find himself on the receiving end of Howard’s ire.

“Goddang it!” he would snap in the middle of meetings. “For the last time, it’s not an outpost! It’s a goddang PRT!”

But the September 11, 2006, attack on Keating’s convoy, and others like it, made it clear to the commanders that the threat to their convoys and to “PRT Kamdesh” was too great, and too frequent, to enable the base to become a true PRT. Feagin’s PRT staff and 3-71 Cav couldn’t exactly start building wells, schools, or water-pipe systems if troops and workers were going to keep being attacked with RPGs every time they left the wire. Security was just too frail.

In fact, those up the command chain who were in charge of PRTs would insist that Kamdesh had never been a definitive location. Yet the 3-71 Cav troops were convinced that it was precisely in order to establish a PRT that they had been working so hard to set up the outpost. In any case, the PRT staff members at the Kamdesh outpost were told in October that when their rotation ended in February, they wouldn’t be replaced. Moreover, Lieutenant Colonel Feagin would be leaving in November, and his replacement would locate at a PRT in Kala Gush, in Nuristan, which would be the only PRT for the province. Whatever plans may have existed for PRT Kamdesh simply were not to be realized. Gooding and others at the base, which the troops had now started calling Camp Kamdesh instead, would still work on development projects, still focus on counterinsurgency, but they would soon be doing so on their own, without the help of the official PRT staff.

CHAPTER 12

Matthias the Macedonian and the LMTV

M

any of Michael Howard’s officers resented him. They thought the lieutenant colonel was all about his own image and his own accomplishments, all about building the northernmost camp in Afghanistan because that demonstrated what a warrior he was. In October, he made a decision that turned that resentment into downright fury, though the men under him never risked charges of insubordination by expressing it directly.

Although more than a quarter million dollars’ worth of work had been poured into repairing the road from Naray to PRT Kamdesh, it remained dangerous—even without the threat of insurgents’ RPGs. A September 2006 analysis had revealed at least sixteen problems limiting, if not in fact precluding, the passage of any vehicle larger than an uparmored Humvee. A more detailed assessment by 3-71 Cav, undertaken little more than a month later, looked at just that part of the road which led from Kamdesh to Mirdesh, not even a tenth of the way to Naray. It identified twelve separate “high-risk” areas that would “greatly hinder trafficability to vehicles larger than a small jingle truck.”

And yet that same month, Howard informed his officers that he wanted to send a truck larger than that from Naray to Kamdesh. He wanted to make sure that 3-71 Cav was 100 percent self-sufficient by ground, he said.

“We’re going to drive an LMTV up there, and we’re going to get it done,” he told Captain Pete Stambersky, referring to a light medium tactical vehicle, a large truck that could carry cargo weighing more than two tons. Because enemy attacks on the road had been increasing, the lieutenant colonel suggested that they go at night. Stambersky laughed. He didn’t think his commander was serious.

“Fuck, Pete,” Howard said. “Are you with me? Are we going to get this done, or not?”

“Roger, sir,” Stambersky replied.

Jesus, Stambersky thought. He really wants to drive an LMTV up that road just to prove it can be done. It doesn’t make any sense.

Major Thomas Sutton, who had replaced Timmons as 3-71 Cav’s XO in June, shared Stambersky’s reservations, knowing that an LMTV weighed around nine tons all by itself, with just fuel and crew. And yet Sutton also understood Howard’s intentions. All of the Afghan contractors’ jingle trucks were getting shot up; the Army needed to put U.S. trucks, big military might, on the road for resupply. Indeed, it was to make such deliveries easier that Combat Outpost Kamdesh had been put near the road in the first place. Helicopters were getting fired upon, and pilots were increasingly reluctant to fly in the area. Now that repairs had been made to the road, Howard wanted to see if an LMTV could make it up there. Sutton assumed that another part of it was “power projection,” as the military called it—flexing muscle to impress the locals.