Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (5 page)

Fenty was relentlessly focused, even compulsive. As part of his continuing education after college, he had studied exercise physiology and kinesiology, the science of human movement, at Troy State University, where he’d learned that wearing a different pair of shoes every day could help guard against lower-leg injuries. When he was in Bosnia, he had a dozen pairs of size 9½ ASICS running shoes, all lined up and rotated daily. This habit amused his roommate, Chris Cavoli, who routinely shuffled Fenty’s shoes out of order to mess with the mind of his anal-retentive friend.

He never stopped running, whether back at the home of the 10th Mountain Division, at Fort Drum, New York, where he and Command Sergeant Major Del Byers had run five to ten miles together daily, or on this deployment in Afghanistan, where the two men took advantage of any opportunity to do the same on U.S. bases.

Fenty always tried to work his brain as much as he did his muscles. He made a great effort to educate himself, reading three newspapers a day when he was at home, taking graduate courses, ordering professional journals, attending lecture series, reading books on military history and critical thinking. He was the kind of self-made man and commander whom a general could trust to assemble a new unit from scratch, as he’d done with 3-71 Cav.

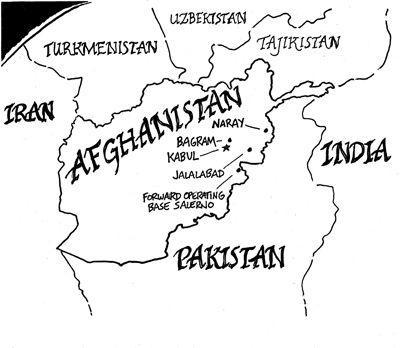

As the convoy slowly traveled the hundreds of miles from Forward Operating Base Salerno, Fenty sat in the front truck commander’s seat of his Humvee, with Berkoff behind him.

Lieutenant Colonel Joe Fenty in his Humvee, March 2006.

(Photo courtesy of Ross Berkoff)

Fenty made it his job to know about his troops and their lives. As they rolled closer to their final destination, he asked Berkoff about his new girlfriend, Rebekah. How had they met?

Actually, Berkoff replied somewhat sheepishly, they’d met online. She was at Syracuse, and he’d been an hour away at Fort Drum, but they both wanted to marry someone Jewish, so they were introduced through J-Date, a website for Jewish singles.

Fenty smiled. He’d met his wife, Kristen, during a spring break in college, he told Berkoff, at a campfire on the beach in St. Petersburg. Fenty and his friends had lost their car keys in the sand, so Kristen and her friend gave them a ride back to where they were staying. She sat on his lap during the drive. Both were students at Belmont Abbey College, and they officially became an item shortly thereafter, on Saint Patrick’s Day. Within two weeks, they knew they would be husband and wife. That’d been twenty years ago.

Fenty talked to his troops to get their minds off the forbidding landscape they were entering. Berkoff described the scene in an email home: “Imagine if you can, driving the road distance equal to driving from Richmond to NYC, but instead of 95 North, you are switch-backing over landscape similar in size to our own Rocky Mountains the entire way, oh yeah, not to mention there are no barriers on the roads keeping your truck from tipping over the cliff.”

Fenty’s chatter also served another purpose: it got his own mind off what he was seeing. This was his second deployment here; in 2002, he had been stationed in northern Balkh Province, where, among other challenging tasks, he’d helped put down a Taliban riot in a detention facility. He knew that some of his soldiers wouldn’t make it home; he accepted that, too. He was all business, yes, but in this place, nobody could be all business all the time.

The Special Forces troops who’d been operating in these provinces since 2002 hadn’t found any of the senior leaders of Al Qaeda, though they had killed or rounded up some lower-level facilitators. The enemy fighters here belonged primarily to three different groups: the Haqqani network from Pakistan, Mullah Omar’s Taliban, and an entity called HIG.

8

Five years earlier, when the Pentagon was planning to attack the Taliban and Al Qaeda in Afghanistan after 9/11, HIG wasn’t on anyone’s radar. Even just one year before this deployment, when Fenty heard the term being bandied about, he didn’t really know what it signified: “HIG”? he thought. Huh? During a May 2005 meeting with 3-71 staff, Fenty—probing his team for information relating to operations and intelligence—bluntly asked his intelligence officer, “Can you tell me exactly what HIG is?” The man—whom Berkoff would soon replace—stared back at his commander. It wasn’t an unreasonable question, especially to ask of an intel officer. But the fact that no one in that room knew what HIG was, almost four years into the war, indicated how poor a job the U.S. Army was doing of preparing its officers for the enemy they would soon have to face.

Berkoff was from Fair Lawn, New Jersey, and had gone through ROTC at Tulane; he was the expert in the room. Indeed, he had learned everything he could about HIG. After all, the Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin led insurgent operations in the region 3-71 Cav was headed for—Kunar and Nuristan Provinces—and Berkoff figured he and his fellow officers, at least, should know who was going to try to kill them.

For Berkoff, working in intelligence provided not only an intellectual challenge but also something of a rush. Deciding where to bring the fight to the enemy, setting his brain to the problem—it could feel like a more muscular exercise than doing a bench press or a curl. Yes, sometimes he felt as though he might as well be throwing darts at a map or shaking a Magic 8 Ball. But if the intel was good, it would mean that shortly thereafter, far fewer insurgents would be hunting him and his friends.

Berkoff explained to Fenty that HIG was an extremist group formed more than a decade before Al Qaeda, during the chaotic years of internal struggle for control of Afghanistan, beginning in the 1970s. After the Afghan government started arresting and executing Islamists in 1974, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a young extremist who had been part of the Muslim Youth organization at Kabul University, fled to Pakistan and founded an Islamist group called Hezb-e-Islami, while also establishing ties with the Pakistani intelligence service ISI. By 1979, Hezb-e-Islami had split into several factions, including Hezb-e-Islami Gulbuddin, or HIG.

9

HIG was among the many groups of mujahideen, or Islamist holy warriors, that had received aid from the U.S. government for their fight against the USSR. Hekmatyar’s faction had in fact evolved into one of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency’s favorite Soviet-killing proxies, receiving more money from the U.S. government than any other single group during that period. The funds were not spent on lollipops; the Soviets considered Hekmatyar to be “the bogeyman behind the most unspeakable torture of their captured soldiers,” as George Crile would later write in

Charlie Wilson’s War

. “Invariably his name was invoked with new arrivals to keep them from wandering off base unaccompanied, lest they fall into the hands of this depraved fanatic whose specialty, they claimed, was skinning infidels alive.”

If the mujahideen groups shared a common Soviet enemy, they often fought one another just as fiercely. After the Taliban seized control of Kabul in 1996, the country became unsafe for Hekmatyar, and he fled to Iran. Although he wasn’t invited to join the interim Afghan government after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, the Iranians kicked him out, so he returned to Afghanistan anyway. Hamid Karzai and Hekmatyar were longstanding enemies, but Hekmatyar initially extended an olive branch to the new Afghan leader. Within weeks, however, Afghan officials claimed to have uncovered a plot by HIG to overthrow Karzai’s government, and more than three hundred fighters loyal to Hekmatyar were arrested. That was the end of the rapprochement. Soon Hekmatyar was targeted—unsuccessfully—by one of the first CIA Predator drone attacks, in May 2002. He subsequently issued a statement: “Hezb-e-Islami will fight our jihad until foreign troops are gone from Afghanistan and Afghans have set up an Islamic government.” In December 2003, tipped off that Hekmatyar and one of his top aides were in a small hamlet in the Waygal Valley in Nuristan, U.S. warplanes pounded the area. Six civilians were killed, including three children. Hekmatyar had left the village hours before.

Berkoff’s briefing was for the benefit of only a select few officers, not the entire squadron; the great majority of the troops had no clue as to what HIG was or how deep ran its fanaticism. They also had no idea that soon enough, members of this group they’d never heard of would be trying to kill them.

As Fenty’s team pushed north, the terrain became lusher and more scenic, with raging rivers and tall mountains. Along the way, the convoy traversed the infamous Khost–Gardez Pass, where Soviet troops had been regularly ambushed two decades before, a tradition now extended to include Americans. Upon reaching Forward Operating Base Gardez, Fenty and his men stopped for the night.

On day two, Fenty’s convoy traveled from Gardez to the outskirts of Kabul and then headed toward Jalalabad Airfield, about a hundred miles away. It was not an easy trip. Berkoff was told that a section of the main road was out between Kabul and Jalalabad, near the Surobi Dam. Not damaged, not under repair, just…

out.

No further explanation was forthcoming or even needed. This was Afghanistan; this was how it was. So the next day, the convoy set off on a long alternate route, switchbacking over mountains, back and forth, back and forth. It took eighteen hours, but everyone made it to Jalalabad alive.

Afghanistan was not a nation known for its robust infrastructure. Summer rainstorms could wash roads out, and even under optimal conditions, a road might be so narrow that a convoy would have to take detours via riverbeds just to get through. If staying dry was a priority, the only other option was to brave the steep cliffs, but that involved no small risk. On the same day that Fenty’s convoy left Khost, a Marine was killed in one of the provinces they would be stopping in—Nangarhar—when his Humvee accidentally rolled over the edge.

10

In Nangarhar, at Jalalabad Airfield, Fenty and his men linked up with a battalion from the 10th Mountain that was headquartered there, the 1-32 Infantry, led by Lieutenant Colonel Chris Cavoli—he of the scrambled running shoes. Loud and gregarious, Cavoli was yin to the reserved Fenty’s yang. Fenty could go for hours without speaking; Cavoli was as restless as a hyperactive child at Mass. During their assignment in war-torn Yugoslavia, Fenty had considerately played country music at low volume, whereas Cavoli had blasted the Clash and Springsteen. And now both men were in Afghanistan. Cavoli and his best friend were excited to see each other, but Cavoli was most interested in the wellbeing of Fenty’s wife, Kristen.

For years, Kristen Fenty had been unable to conceive a child. That had been okay with her husband: the two of them moved around a lot, and their life style wasn’t conducive to parenthood. They were pretty satisfied with things the way they were. All of that changed in the summer of 2005, however, when Kristen Fenty—at the age of forty—got pregnant. Their little girl was due in April.

From: Joe Fenty

Sent: Friday, March 17, 2006

To: Kristen Fenty

Dear, hope all is well. I’m traveling but sure would like to get a note from you. Please let me know how you’re feeling. The timing is awful. I’m going to be at the most remote place on the due date….

Miss you and love you,

Joseph

From: Kristen Fenty