Read The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor Online

Authors: Jake Tapper

Tags: #Terrorism, #Political Science, #Azizex666

The Outpost: An Untold Story of American Valor (74 page)

Mullah Sadiq in Kamdesh in the fall of 2009, a photograph given to the members 3-61 Cav as a “confidence-building measure” to show that he was back from Pakistan.

(Photo courtesy of Lieutenant Colonel Brad Brown)

Sadiq, Colonel Rahman insisted, was not a bad guy. Born into a poor family, he had nevertheless gone to school and was relatively well educated; more important, he was extremely well respected in Kamdesh. After doing some research, Brown learned that Sadiq had actually shared information with U.S. Special Forces when they first arrived in Naray, until they got caught up in a historical grudge dating back to the 1986 murder of mujahideen leader Mohammed Anvar Amin—a feud layered atop an age-old land dispute.

77

Amin’s son, a well-connected contractor, blamed his father’s death on Sadiq, and he was the informant who told a U.S. Special Forces team that the HIG leader was working with the Taliban and Al Qaeda, thereby causing him to be placed on the “kill/capture” list.

After checking with his chain of command, on September 6, Brown sent a letter to Sadiq. “In previous years, the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan and International Security Forces have worked in close partnership with the shuras and elders throughout Kamdesh District,” he wrote. “We would like to rebuild this friendship and return peace to Nuristan, and ask your assistance and wisdom in this effort.”

He felt he needed to put the last few years in context, and to apologize for anything that Sadiq might object to, particularly as it related to Afghan casualties. He continued:

Many civilians have been injured and killed during the fighting, and I offer apologies to the Nuristani people for the bombings that hurt the innocent. We would like to provide support to the people who have suffered in the fighting, and resume development projects to improve the lives of people throughout Kamdesh. But this can only begin when leaders from all the villages work together to provide security.

The Taliban, funded and resourced by criminals in Pakistan, has been able to influence and recruit the young men of Kamdesh to fight the Afghan National Army, Police, and Coalition Forces. We need assistance from leaders like you that are able to reach out and encourage the people of Kamdesh to cease the violence and oust the Taliban. We ask for your guidance in developing a plan that will improve security and development in Kamdesh. The sooner the people of Kamdesh are able to secure themselves from outside influences, the sooner Coalition Forces will be able to return to their homes and families.

In order to better resolve the security problem in Kamdesh, we invite you, or a trusted associate, to attend a shura to discuss security and cooperation. I offer you my personal protection during this meeting. We are willing to meet at the coalition base in Naray or Urmul, at the Afghan Border Police Headquarters in Barikot, the Naray District Center, or any place that is convenient for you.

He ended the letter by saying that he looked forward to working with Sadiq “to help bring peace and development to the people of Kamdesh.”

Brown gave copies of the letter to Colonel Rahman and the Afghan Border Patrol commander Brigadier General Zaman, who had been a member of HIG when the mujahideen were fighting the Soviets. They said they would get it to Sadiq.

Brown hoped he hadn’t just made a big mistake.

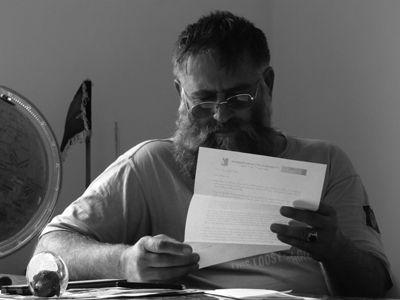

Colonel Shamsur Rahman reading Lieutenant Colonel Brad Brown’s letter to Sadiq.

(Photo courtesy of Lieutenant Colonel Brad Brown)

CHAPTER 28

C

aptain Stoney Portis could have been a character straight out of one of the books written by his dad’s cousin Charles Portis, author of

True Grit

. Lean and handsome, polite and determined, Stoney Portis was the quintessential soldier. He’d grown up in Niederwald, Texas—“Population: twenty-three,” he would later quip. He had to go to the next town, Lockhart, for high school—not that Lockhart was exactly a booming metropolis.

Portis had thought he was going to take command of Black Knight Troop, and relieve Porter at the outpost, immediately after arriving in Afghanistan. But instead he was sent to Jalalabad; Colonel George felt he was needed more immediately in charge of planning missions for the 4th Special Troops Battalion, which contained an intelligence company, a signal communications company, a reconnaissance troop, and two military police companies. That was Portis’s charge until August, when George drove from Forward Operating Base Fenty in Jalalabad to Forward Operating Base Finley-Shields,

78

just down the road. It was only then that he told Portis it was time for him to replace Melvin Porter.

Portis’s father worked for Texas Parks and Wildlife and was a farmer, cattle rancher, and welder. His mother, an elementary school teacher, had died of leukemia when he was sixteen. She had taught Portis and his siblings about the importance of serving, whether through the military, teaching, or the church. Portis’s brother and sister both taught high school; his brother was also a youth minister, and his sister for a time had been a missionary in Mexico. Portis’s father, an Army veteran, pushed him to go to West Point first if he was going to join the Army; his experience was that officers by and large got to make the decisions, and if his son ever got put in a bad position as a soldier, he wanted him to be the one calling the shots.

Stoney graduated from West Point in 2004. Inside his West Point ring, which he wore on his ring finger next to his wedding band, was an inscription from the book of Isaiah, chapter 6, verse 8:

Then I heard the voice of the Lord saying, “Who will go for us, whom shall I send?” And I said, “Here I am. Send me!”

On August 27, 2009, Portis flew in to Forward Operating Base Bostick, where he met with various officers who briefed him on Camp Keating; Lieutenant Colonel Brown was not among them, since he was actually

at

Keating at the time. Air travel in and around Kamdesh was difficult, as Portis would soon learn. On the night of September 2, 2009, he flew to Observation Post Fritsche, where he met with Lieutenant Jordan Bellamy and White Platoon. The place felt to him like an old Western outpost on the edge of Indian country, like Fort Apache—a solitary compound in the middle of nowhere. Two days later, accompanied by a patrol from White Platoon, Portis walked down from the observation post, heading for Camp Keating.

In his more than ten years in the Army, this was the first time Portis ever got blisters. His whole walk down the Switchbacks, he kept thinking, If I were Taliban, I’d shoot at ’em from here and hide behind this tree and escape that way. Over and over, so many places from which to fire. It was only when they were coming down that last stretch of mountain that he first appreciated where Combat Outpost Keating was. Shocked, he could say only, “Holy shit.”

Portis didn’t know about Rob Yllescas, or Tom Bostick, or Ben Keating. He’d heard their names, but he didn’t know their stories. Soon he met Porter, who told him—inaccurately—that Captain Pecha, his predecessor, had stopped patrolling and never left the operations center because he believed he was going to die at Camp Keating. Awesome, Portis thought. I’m the enemy’s new number-one high-value target, and I didn’t even know it. Add to that the good news that the U.S. Army had placed the outpost in what he considered to be the most tactically disadvantageous terrain possible, and there weren’t many reasons for Portis to be happy about his new assignment.

He was, however, relatively impressed with the soldiers and his new subordinate leaders. When they needed to relieve themselves, the men of 3-61 Cav would put on full body armor just to head to the piss-tubes, even in 100-degree heat. It was a tremendous nuisance, but they did it anyway. That said something good about their willingness to follow orders, no matter the discomfort and inconvenience. That was a good sign, Portis thought, because Black Knight Troop was living under the most austere and harsh conditions he’d ever seen.

Portis walked around the camp and got his lay of the land. When he entered the shower trailer, Kirk and Rasmussen happened to be in there, on the cusp of disrobing. With his captain’s bars, in this remote locale, Porter could have been no one other than the new commander. Kirk turned to Rasmussen and said, “All right, let’s get naked.” He dropped his shorts and, as God made him, walked over to Portis and stuck out his hand to greet him. “You must be the new commander,” he said. “I’m Sergeant Kirk.”

Classic Kirk.

Melvin Porter briefed Stoney Portis for three days, and it became clear to the new commander that the men at Camp Keating desperately needed to figure out how to build up its defenses. He’d heard the whispers, of course, that the camp could be shut down at any moment, but until that happened, he would proceed as if he and his newly assigned troops were going to be there until July 2010, when they would hand the outpost over to the next company. From eye level, the camp looked generally fortified. The HESCOs were in place, and there was double- and triple-strand concertina wire enveloping the camp. There certainly were some defensive positions that Portis wanted to improve—first off, he thought, there was too much dead space near the camp’s entry control point of the camp. He understood, however, that there were limits to how much could be done to make the men safe. “COP Keating is practically worthless,” he wrote in his journal. “It’s in a bowl with high mountains all around us.” There were roughly fifty troops here just trying to exist; their only mission was survival.

Almost immediately, it was evident that Portis was going to be different from Porter. For example, he had a different reaction to the incoming AK-47 and RPG fire from the Putting Green. Hearing it come in, he stepped outside the operations center and looked up with his binoculars at the northwestern mountain.

“Sir, you might want to get behind some cover,” suggested “Doc” Courville.

“Yeah,” Portis replied absentmindedly. He went back inside the operations center to get his radio. Lieutenant Carson Shrode was in there, on the radio with John Breeding in the mortar pit. “Hey,” Portis told Shrode, “you need to put five rounds of ‘Willie Pete’ ”—white phosphorous—“up there now.”

Portis walked down the hall, and Shrode ran after him. “Did you just say you want Willie Pete at this grid?” Shrode asked.

“Yeah,” Portis said. “And I want it fucking now.”

“You sure?” Shrode asked. Portis was. There were no civilians at the location from which the enemy was firing, so there was no reason to hesitate.

Shrode got back on his radio and told a still-skeptical Breeding, “No, he’s serious.” Portis glared at Shrode, pissed that his instructions been questioned, let alone debated, in front of other soldiers. “If Willie Pete works,” he said bluntly, “use it.”

There was a new sheriff in town.

Portis’s aunt and uncle had heard the troops lacked even basic equipment, so they sent him a care package that included some Leatherman Multi-Tools, a device containing a knife, pliers, wire cutters, a saw, a hammer, and on and on. Portis told his three platoon leaders each to select a soldier to receive one of the Multi-Tools—someone deserving of special, if informal, recognition.