The Oxford History of the Biblical World (17 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

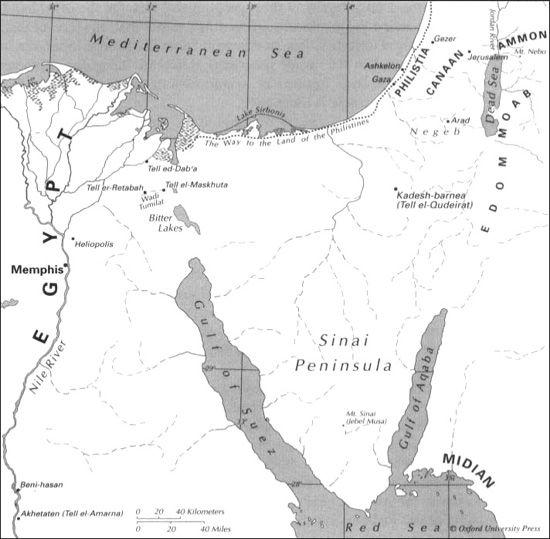

The sacred “mountain of God” also cannot be placed on a map. The biblical narrative refers to the mountain, when it is given a name, by two different appellations, Mount Horeb and Mount Sinai. Scholars do not agree whether the traditions refer to one or two mountains (although the weight of current opinion favors one mountain), let alone where one or the other mountain might be located. Suggestions for locating the mountain of God range from the southern Sinai Peninsula, to the Negeb, and even to the Arabian peninsula.

The crossing of the Red Sea has also touched off much discussion. Hebrew

yam suf

has been translated both as Red Sea and as Reed Sea; cogent grounds exist in support of both translations. There are biblical passages where

yam suf

is clearly unrelated to the Exodus and unquestionably refers to the Red Sea (such as 1 Kings 9.26). Moreover, both the Greek Septuagint and Latin Vulgate versions of the Bible render

yam suf

as “Red Sea,” reflecting traditions current at the time these two translations were made (third century

BCE

and fourth century

CE

, respectively). But there are also philological grounds for translating

yam suf

as “Reed Sea,” and in light of this interpretation scholars have sought to localize the destruction of Pharaoh’s army in reed beds located in the northeastern Nile Delta. Such reed beds have in fact existed at various points along the northeastern Egyptian border in locations ranging from the Bitter Lakes in the south to Sabkhat el-Bardawil (classical Lake Sirbonis) adjacent to the Mediterranean coast in the north. A plausible case, for which there is no real support other than its plausibility, can be made for Bardawil as the location of the crossing of the Red Sea. The lake is separated from the Mediterranean Sea by only a thin strip of land, and violent storms have been known to lash the sea and cause sudden and intense flooding of the region. There are even historical parallels where ancient troops were trapped and partially destroyed by just such a storm.

Traditionally, two routes have been proposed for the Exodus: a southern

route through southern Sinai and a northern one along the Mediterranean coast (although Exod. 13.17–18 expressly states that the latter, anachronistically called “the way of the land of the Philistines,” was not taken by the Israelites). Recent studies emphasizing both the modern and the past ecology and ethnography of the Sinai Peninsula suggest, however, that four major east-west routes ran through Sinai in antiquity. The northernmost hugs the Mediterranean coast; the other three follow desert wadis, the main channels for water and communication through the huge, barren peninsula. Apart from the north coastal strip, the remainder of the approximately 36,000 square kilometers (23,000 square miles) that make up the Sinai Peninsula has few economic resources and little water, and its population has always been minimal. The largest concentration of ancient settlements occurs in mountainous and geographically isolated south-central Sinai. Here are found both an adequate water supply and a comfortable climate. The difficult terrain, the physical isolation, and the relatively hospitable living conditions all combine to make this area a prime candidate for the location of the Israelite sojourn in the wilderness. Equally important, the region was apparently never of any interest to Egypt: none of the ancient settlements in the area appear to be Egyptian, and there are no indications of ancient Egyptian suzerainty. At the same time, however, none of the ancient settlements in the area date to a period that might relate to an Israelite Exodus from Egypt: they are too early (Early Bronze Age) or too late (Iron Age). The localization of the wilderness sojourn in south-central Sinai therefore is an attractive but unproven hypothesis.

The Sinai Peninsula

Research into the monastic settlements in south-central Sinai suggests that it was the establishment of the monastic population in this area during the Byzantine period (fourth to seventh centuries

CE

) that resulted in the identification of southern Sinai sites with various biblical locations. Most likely, the monks themselves generated the traditions of the southern Exodus route; the traditions arose along with the monasteries. At the same time as the monastic movement established itself in southern Sinai, Christian pilgrimages also were becoming popular. These pilgrimages further stimulated the development of monastic traditions both by encouraging the local placement of Exodus sites and, once made, by reinforcing those localizations. Pilgrimage practice thus helped preserve and perpetuate the very geographical identifications that it had helped create. As time passed the site correlations moved into popular lore and became sanctified tradition. Such a process is not unparalleled. Helena, mother of the Roman emperor Constantine, traveled throughout the Near East dreaming of the locations of various events in the life of Jesus. Over the years her identifications, some no doubt based on prior popular belief, became accepted as indigenous local traditions. This mechanism for creating and reinforcing popular tradition is not confined to antiquity: the renaming of Tell el-Qudeirat as Tel Kadeshbarnea is a modern example.

Thus, despite decades of research, we cannot reconstruct a reliable Exodus route based on information in the biblical account. Nor, despite intensive survey and exploration by archaeologists, are there remains on the Sinai Peninsula or in Egypt that can be linked specifically to the Israelite Exodus. Barring some future momentous discovery, we shall never be able to establish exactly the route of the Exodus.

The biblical narrative also informs us about the length of the Israelite sojourn in Egypt and the date of the Exodus. The data are not, however, consistent. Thus, 1 Kings 6.1 dates the Exodus to “the four hundred eightieth year after the Israelites came out of the land of Egypt, in the fourth year of Solomon’s reign over Israel.” Although we do not know the exact year of Solomon’s accession to the throne, we know its approximate date, the mid-tenth century

BCE

. This would date the Israelite departure from Egypt in the mid-fifteenth century. Exodus 12.40 tells us that the Israelites lived in Egypt for 430 years prior to the Exodus; this gives the early nineteenth century for the coming of Jacob and his sons into Egypt. In Genesis 15.13, however, the length of the sojourn in Egypt is given as four hundred years; and in Genesis 15.16, the time shrinks to three generations. Moreover, the figure of 480 years is suspiciously schematic: the Bible assigns twelve (a favorite and symbolic biblical number) generations between the Exodus and Solomon, and the standard biblical length of a generation is forty years.

The numbers given for the participants in the Exodus events are impressive, and improbable. Exodus 12.37–38 states: “The Israelites journeyed from Rameses to Succoth, about six hundred thousand men on foot, besides children. A mixed crowd also went up with them, and livestock in great number”; the report of the census in Numbers 1.46 reiterates this figure. By the time one adds women and children—and anyone else subsumed under the rubric of “mixed crowd”—it is a mass of people, at least 2.5 million, that is moving out of Egypt. Such a number, particularly when combined with “livestock in great number,” would have constituted a logistical nightmare and is impossible; if all 2.5 million people marched ten abreast, the resulting line of more than 150 miles would need eight or nine days to march past any single fixed point. Taken at face value, such a host could not have crossed any ordinary stretch of water by any ordinary road or path in one night; nor could these numbers, or anything remotely approaching them, have been sustained in the inhospitable Sinai desert. Modern census figures suggest a current total of approximately forty thousand bedouin for the entire Sinai Peninsula; in the late nineteenth century

CE

the figure was under five thousand. The entire population of Egypt in the mid-thirteenth century

BCE

has been estimated at 2.8 million.

One hint of a more feasible figure for participants in the flight from Egypt is the reference in Exodus 1.15 to two Hebrew midwives; unusually, the midwives are even named. Together, the two met the needs of the entire Hebrew community sojourning in Egypt: in this case certainly not the hundreds of thousands or even thousands of women implied in a census of over half a million men. Perhaps, then, the two mid-wives reflect a superseded and now lost tradition of a much smaller group dwelling within and presumably departing from Egypt.

Biblical dates and numbers are thus indifferent to concerns of strict historical accuracy. As with other details, the biblical reckonings are subservient to theological images and themes. The improbabilities of the data can be rationalized in different ways: but once rationalized, they lose their claim to ancient authority, historical or otherwise.

The biblical account makes an exceptionally poor primary historical source for the Exodus events. Possible historical data are mostly inconsistent, ambiguous, or vague. No Egyptian pharaoh associated with the Exodus events is named. When the king of Arad fights the Israelites in Numbers 21.1, he is merely called “the Canaanite, the king of Arad.” In those few places where the Exodus narrative is meticulous about detail, the particulars are either unhelpful—such as the stages in the trek out of Egypt, or the names of the three Transjordanian rulers (King Sihon of the Amorites in Num. 21.21; King Og of Bashan in Num. 21.33; Balak, son of Zippor, king of Moab, in Num. 22.4) who are completely unknown outside the Bible—or inappropriate. In the latter case, biblical precision generally stems from concerns other than historical: standardized generation formulas grounded in symbolic numbers are applied backward to calculate the year of the Exodus; or historically impossible numbers are given for participants in the departure from Egypt to stress the event’s significance.

The surviving biblical account of the Exodus has thus been shaped by later creative hands responding to overarching theological agendas and differing historical and

cultural circumstances. Many of the preserved details are anachronistic, reflecting conditions during the first millennium

BCE

when the narrative was written down and repeatedly revised. As a consequence the final Exodus account should not be accepted at face value, nor can it function as an independent historical variable against which other sources of historical information are judged. Rather, it is a dependent variable whose historical value is judged by and against other, more reliable sources of historical information.

Over the past two centuries, scholars have learned an enormous amount about the ancient world. Vast quantities of raw data, both textual and archaeological, have been collected and processed; innumerable synthetic works have been produced; and anthologies of primary and secondary sources have proliferated. Granted, our knowledge is not perfect; a number of variously sized holes in our understanding remain to be filled, and individual historical sources can be problematic. Collectively, however, the weight of accumulated historical knowledge is both impressive and indisputable—and almost without exception decisive for larger issues of historical understanding.

Synchronisms among the ancient Mediterranean, Egyptian, and Near Eastern cultures have been worked out slowly and carefully by scholars in a variety of related fields. There is some quibbling in the decorative details of this structure, particularly for more poorly known eras, but the framework as a whole is solid. Absolute dates are disputed within a limited chronological range, but this does not mean that separate parts of the whole can be treated individually without regard to the broader implications for the entire structure. All parts are interrelated, and shifting one or more segments of the framework requires a concomitant movement of all other associated elements. Any substantive modification must be warranted on cogent historical grounds. The biblical narrative in particular, with its inherent inconsistencies, contradictions, and clearly problematic historical base, is not an appropriate venue for arbitrarily challenging fastidiously constructed and well-established chronologies and cross-cultural synchronisms.

Any search for a historical core to the Exodus saga must thus work within the network of established and interdependent chronologies for Egypt and the ancient Near East. The first step is to seek mention of Exodus events in nonbiblical ancient sources. Unfortunately, there are none: no texts from Egypt or anywhere else in the ancient Near East provide such an independent witness. Years of the most intensive scrutiny have failed to produce a single unequivocal, or even generally accepted, nonbiblical historical reference to any event or person involved in the Exodus saga. The first reasonably secure date in all of biblical history is Solomon’s death around 928

BCE

; and with one exception, no extrabiblical reference to Israel or Israelites by name occurs in historical sources earlier than the ninth century.