The Oxford History of the Biblical World (62 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

At this juncture Judah submitted to Babylonia, but not without bitter internal controversy. The voices of those who urged surrender to Nebuchadrezzar, most prominent among them the prophet Jeremiah, were antagonistically received. The high drama of those days can be grasped by a chapter from the biography of Jeremiah (Jer. 36). No newcomer to Jerusalem, the prophet had been expounding the word of his God since the days of Josiah. His warning that continued disregard of the covenant demands for justice and righteousness in public life would lead to God’s punishing his people was more than once met with scorn and outright hostility. The antagonism between the king and Jeremiah must have been particularly great following the prophet’s censure of his sanguineous extravagances. Not surprisingly, therefore, on this particular occasion, Jeremiah chose to send Baruch, his secretary and friend, to read his words to those assembled at the Temple; he himself was barred from appearing there because of an earlier altercation with the authorities. Jeremiah predicted dire consequences if they resisted Babylonia. It was a chimera to believe that the Temple would offer them refuge, for it, too, was forfeit, just as the old premonarchic sanctuary in Shiloh had been handed over for destruction to the Philistines. His words were immediately brought to the king’s attention, and though some ministers supported the prophet’s stand, Jehoiakim derisively consigned Jeremiah’s scroll to the fire section by section as the scroll was read, and ordered both the prophet and his secretary arrested. In the end, Jehoiakim did submit to Nebuchadrezzar, although he soon found reason to switch loyalties.

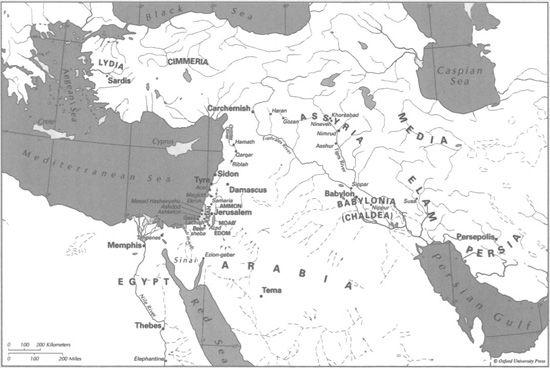

The Near East during the Neo-Babylonian Empire

Nebuchadrezzar suffered a major setback in his attempt to invade Egypt in 601 and was forced to return to Babylonia to refit his army. This information is recorded in the Babylonian Chronicle as the main event in Nebuchadrezzar’s fourth year, and it is a striking example of the evenhandedness of that ancient source. In the wake of his victory, Neco moved against Gaza, thus moving Egypt’s border to the northern Sinai once again; Jehoiakim returned to his pro-Egyptian stance. Babylonian garrison troops stationed in the west took the lead in trying to bring Judah back into line, until Nebuchadrezzar himself appeared on the scene. Despite Egypt’s proximity, Neco lent no support to his erstwhile client in Jerusalem. The outcome is reported in the Babylonian Chronicle in summary fashion:

Year 7 [of Nebuchadrezzar]. In the month of Kislev [December 598], the king of Babylonia mobilized his troops and marched to the west. He encamped against the city of Judah [Jerusalem], and on the second of Adar [16 March 597], he captured the city and he seized [its] king. A king of his choice he appointed there; he to[ok] its heavy tribute and carried it off to Babylon.

Sometime during the Babylonian siege of Jerusalem, Jehoiakim died under unknown circumstances—there is even suspicion of assassination. His son Jehoiachin assumed the throne, but within three months he submitted and threw himself upon the mercy of Nebuchadrezzar. The young Jehoiachin was indeed spared, living out his life in exile. Deported together with the king were members of the royal household and the court, as well the city’s elite—officers of the army and its premier fighting units and skilled craftsmen and smiths all found themselves on the road to Babylon, where they would be employed in state service. Their total number reached some ten thousand persons, more than enough for the start of what was to become a flourishing community in exile. Foremost among the spoils were the state and Temple treasuries, including golden vessels dedicated by King Solomon. Thus, when Zedekiah, Jehoiachin’s uncle and the last son of Josiah to attain the throne, was installed as a Babylonian vassal king, he took over a land much impoverished, depleted of both human and material resources.

Zedekiah’s eleven-year reign, as tumultuous as any in Judah’s recent history, would be the kingdom’s final decade as a sovereign state. Rather than maintaining loyalty to his liege and overlord, as might have been expected, Zedekiah seized every opportunity

to break free from Babylonia. To suggest youth and inexperience as the causes of this policy would be to engage in modern psychohistory. On the other hand, it is understandable that observers in the west might have thought that Babylonia was going into decline. After his victory at Jerusalem, Nebuchadrezzar faced several serious threats to his rule. During the next three years, he met Elam on the eastern front and put down a rebellion among army officers at home. In each case, Nebuchadrezzar overcame his enemies, but to some, these events suggested that the time was ripe to regain independence. Thus, in the late summer of 594

BCE

, a regional conclave convened in Jerusalem to plan joint action against Nebuchadrezzar. Among the participants were delegates from Edom, Moab, Ammon, Tyre, and Sidon. Egypt stood conspicuously aloof, Neco having died the previous winter and his successor, Psammetichus II (595–589), finding himself engaged in strengthening his southern border.

Talk of rebellion was everywhere, and the leadership in Judah was clearly divided over the issue. Once again, Jeremiah found himself confronting the anti-Babylonian faction in heated debate. He demonstrated his disapproval of their actions by appearing before those assembled at the Temple wearing a yoke of straps and bars on his neck, symbolic of the yoke of the king of Babylon that God had placed on the nations, not to be removed. The prophet also warned against the false hopes spawned by other prophets that the exiles would soon return. Through his contacts with that community, he knew that the unrest had reached them, and that several of their leaders had been executed by Nebuchadrezzar. Among those present at the Temple when Jeremiah spoke was Hananiah, son of Azur from Gibeon, who to the dismay of the crowd and the prophet himself removed the yoke from Jeremiah’s neck. Breaking the yoke, Hananiah prophesied that just so would God “break the yoke of King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylon from the neck of all the nations within two years” (Jer. 28.11).

In the end, the rebellion did not come off. Apparently a decision could not reached by the delegates, but Zedekiah was summoned that winter to appear personally before Nebuchadrezzar while the Babylonian king was on campaign in northern Syria, in all likelihood to explain his conspiratorial activities and to pledge renewed loyalty.

In 592, Egypt reappeared on the stage. Fresh from his victory in Nubia, Psammetichus II planned and executed a triumphal visit of his court and army to Philistia, Judah, and the Phoenician cities of Tyre and Sidon: “Let the priests come with the bouquets of the gods of Egypt to take them to the land of Kharu [Syria] with Pharaoh” (Papyrus Rylands IX, 14.16–19). Babylonia’s failure to react to this irruption into its holdings most likely stoked the smoldering embers of rebellion among its Syrian vassals, although the lengthy illness and death of Psammetichus delayed open uprising. But in early 589 the new pharaoh Apries (589–570

BCE

; called Hophra in the Bible) showed his intention to continue the vigorous policy of his predecessor, launching a foray into the mountains of Lebanon. With the promise of Egyptian support in materiel and an auxiliary fighting force, Zedekiah finally broke with Nebuchadrezzar.

Only the final stages of the Babylonian retaliation against Judah can be discussed, and this merely in outline. Biblical sources focus on the siege of Jerusalem, and the parts of the Babylonian Chronicle covering these years no longer exist. Archaeological

investigation, however, adds perspective: excavations at many major sites in Judah have uncovered destruction levels of burnt debris and ruins properly ascribed to the Babylonian army, either in its campaign of 598 or in that of 587. On the other hand, a number of Judean sites, particularly north of Jerusalem, show evidence of continuity, with undisturbed occupation levels into the sixth century

BCE

. In the key fortress of Lachish in the Judean lowlands, a collection of over twenty Hebrew ostraca was found in the rubble by the gateway; they are part of the correspondence received by Yoash, apparently commander of this strategic post, during the period of the Babylonian operations in Judah, and they hint tantalizingly at matters known to the addressee but hidden from the modern reader. One letter informs Yoash that “we are watching for the signal fires of Lachish according to signs which my lord set, for we cannot see Azekah.” Yoash was also apprised that “the army officer Coniah son of Elnathan came down in order to go to Egypt and he sent to take from here Hodaviah son of Ahijah and his men. And your servant is sending you the letter of Tobiah, the king’s servant, which came to Shallum son of Jaddua through the prophet, saying ’Beware!’ “

Jerusalem came under siege in January 587, holding out for eighteen months until the summer of 586. The arrival of Egyptian forces did provide a short respite as the Babylonian army withdrew to meet them, but not for long. After the defeat of the Egyptians, who had once again shown themselves to be an unreliable “broken reed of a staff’ (2 Kings 18.21), the siege resumed. In the end, severe hunger brought the city to its knees. The walls of Jerusalem were breached, probably on the north, where the topography lends itself to the setting up of siege machinery, and where a great quantity of Babylonian-style arrowheads have been recovered. Zedekiah tried to escape to the Jordan Valley and from there abroad, but he was captured and hauled before Nebuchadrezzar, who was encamped at Riblah in central Syria. After watching his sons’ execution, the king was blinded—a common punishment of rebellious slaves—and sent off to exile. Meanwhile, the order was given to complete the deportation and to destroy the city. The ringleaders of the rebellion were rounded up, shipped off to Riblah, and summarily put to death, and the final destruction took place:

In the fifth month, on the seventh day of the month—which was the nineteenth year of King Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon [16 August 586]—Nebuzaradan, the captain of the bodyguard, a servant of the king of Babylon, came to Jerusalem. He burned the house of the L

ORD

, the king’s house, and all the houses of Jerusalem; every great house he burned down. All the army of the Chaldeans who were with the captain of the guard broke down the walls around Jerusalem. Nebuzaradan the captain of the guard carried into exile the rest of the people who were left in the city and the deserters who had defected to the king of Babylon—all the rest of the population. (2 Kings 25.8–11)

How lonely sits the city

that was once full of people!

How like a widow she has become,

she that was great among the nations!

She that was a princess among the provinces

has become a vassal.

(Lam. 1.1)

In this verse, the opening line from the book of Lamentations, one feels the great sense of personal and national loss that the destruction of Jerusalem engendered. Laments over destroyed cities and sanctuaries form a distinct literary genre in ancient Mesopotamia, with roots reaching as far back as the early second millennium

BCE

. The poems collected in the biblical book of Lamentations probably belong to this genre, and they may have been recited at the site of the ruined Temple as part of a ritual of commemoration on designated fast days. The book is traditionally ascribed to Jeremiah, but this cannot be established; similar style and language are common to several of the prophet’s contemporaries, and the viewpoint expressed in Lamentations is most unlike his pronouncements. Rather, the impression is that the poet (or poets) was a member of Zedekiah’s court, a veteran Jerusalemite, overcome with remorse by the grievous suffering of the city and its population. The poet acknowledges Israel’s guilt, for which God had brought on her deserved punishment, but beyond this he mentions no specific sin. One wonders whether this indefiniteness results from the lament style or from the poet’s inability to comprehend the enormity of the tragedy. Like the author of the book of Kings, the poet points to the nation’s leaders as the culprits:

Your prophets have seen for you

false and deceptive visions;

they have not exposed your iniquity

to restore your fortunes,

but have seen oracles for you

that are false and misleading.

(Lam. 2.14; see also 4.13)

In the end, however, God’s justice holds out hope for forgiveness and renewal. And with such confidence as their support, many exiles endured the hardships of life in distant Babylonia.

One might expect, or at least regard it as understandable, that Judah’s conquerors would have been the prime focus of vengeful fulminations on the part of the survivors as they vented their grief and anger over the destruction. Yet surprisingly it is not the Babylonians but the Edomites who are most reviled for their behavior at the time:

Your iniquity, O daughter Edom, [the Lord] will punish,

he will uncover your sins.