The Oxford History of World Cinema (18 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

industry, writing brief scenarios and acting for both the Edison and Biograph companies.

In the spring of 1908 the Biograph front office, facing a shortage of directors, offered

Griffith the position and launched him, at the age of 33, on the career which most suited

him.

Between 1908 and 1913 Griffith personally directed over 400 Biograph films, the first,

The Adventures of Dollie, released in 1908 and the last, the four-reel biblical epic Judith

of Bethulia, released in 1914, severl months after Griffith and Biograph had parted

company. The contrast between the earliest and latest Biograph films is truly astonishing,

particularly with regard to the aspects of cinema upon which Griffith seems to have

concentrated most attention, editing and performance. In terms of editing, Griffith is

perhaps most closely associated with the elaborate deployment of cross-cutting in his

famous last-minute rescue scenes, but his films also exerted a major influence upon the

codification of other editing devices such as cutting closer to the actors at moments of

psychological intensity. With regard to acting, the Biograph films were recognized even at

the time as most closely approaching a new, more intimate, more 'cinematic' performance

style. Several decades after they were made, the Biograph film continue to fascinate not

only because of their increasing formal sophistication, but also because of their

explorations of the most pressing social issues of their time: changing gender roles;

increasing urbanization; racism; and so forth.

Increasing chafing under the conservative policies of Biograph's front office, particularly

the resistance to the feature film, Griffith left Biograph in late 1913 to form his own

production company. First experimenting with several multi-reelers, in July 1914 Griffith

began shooting the film that would have assured him his place in film history had he

directed nothing else. Released in January 1915, the twelve-reel The Birth of a Nation, the

longest American feature film to date, hastened the American film industry's transition to

the feature film, as well as showing cinema's potential for great social impact. The Birth

also had a profound impact upon its director, for in many ways Griffith spent the rest of

his career trying to surpass, defend, or atone for this film.

His next feature, Intolerance, released in 1916, was a direct response to the criticism and

censorship of The Birth of a Nation, as well as an attempt to exceed the film's spectacular

dimensions. Intolerance rather unsuccessfully weaves together four different stories all

purporting to deal with intolerance across the ages. The two most prominent sections are

'The Mother and the Law', in which Mae Marsh plays a young woman attempting to deal

with the vicissitudes of modern urban existence, and 'The Fall of Babylon', dealing with

the Persian invasion of Mesopotamia in the sixth century and featuring massive, elaborate

sets and battle scenes with hundreds of extras. In an editing

tour de force,

the film's

famous ending weaves together last-minute rescue sequences in all four stories. The third

of the important Griffith features, Broken Blossoms, is by contrast a relatively smallscale

effort focused on three protagonists, an abused teenager, played by Lillian Gish in one of

her most impressive performances, her brutal stepfather, Donald Grisp, and the gentle and

symathetic Chinese who befriends her, this role, as enacted by Richard Barthelmess,

clearly intended to prove that Mr Griffith was no racist after all.

After the release of Broken Blossoms in 1919, Griffith's career began a downward

trajectory, both artistically and financially, which he never managed to reverse.

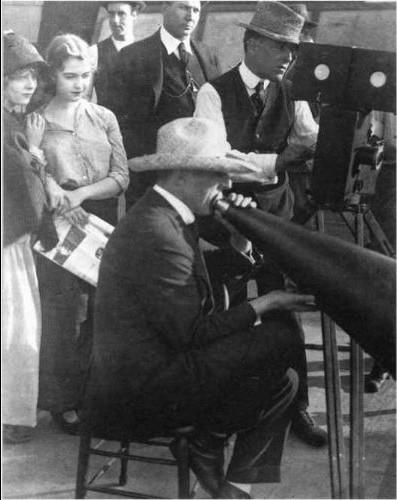

D. W. Griffith on set, with cameraman Billy Bitzer and E. Dorothy Gish

Plagued to the end of his life by the financial difficulties attendant upon an unsuccessful

attempt to establish himself as an independent producer-director outside Hollywood,

perhaps more importantly Griffith never seemed able to adjust to the changing

sensibilities of post-war America, his Victorian sentimentalities rendering him out of sync

with the increasingly sophisticated audiences of the Jazz Age. Indeed, the two most

important Griffith features of the 1920s, Way Down East ( 1920) and Orphans of the

Storm ( 1921), were cinematic adaptations of hoary old theatrical melodramas. While

these films have their moments, particularly in the performances of their star Lillian Gish,

they none the less look determinedly back to cinema's origins in the nineteenth century

rather than demonstrate its potential as the major medium of the twentieth century.

Making a serise of increasingly less impressive features throughout the rest of the decade,

Griffith did survive in the industry long enough to direct two sound films, Abraham

Lincoln ( 1930) and The Struggle ( 1931). The latter, a critical and financial failure,

doomed Griffith to a marginal existence in a Hollywood where you are only as good as

your last picture. He died in 1948, serving occasionally as script-doctor or consultant, but

never directing another film.

ROBERTA PEARSON

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Shorts The Song of the Shirt

( 1908); A Corner in Wheat ( 1909); A Drunkard's Reformation ( 1909); The Lonely Villa

( 1909); In Old Kentucky ( 1910); The Lonedale Operator ( 1911); Musketeers of Pig

Alley ( 1912); The Painted Lady ( 1912); The New York Hat ( 1912); The Mothering

Heart ( 1913); The Battle of Elderbush Gulch ( 1914)Features Judith of Bethulia ( 1914);

The Birth of a Nation ( 1915); Intolerance ( 1916); Broken Blossoms ( 1919); Way Down

East ( 1920); Orphans of the Storm ( 1921); Abraham Lincoln ( 1930)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Gunning Tom ( 1991),

D. W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film

.

Pearson, Roberta E. ( 1992),

Eloquent Gestures: The Transformation of Performance

Style in the Griffith Biograph Films

.

Schickel, Richard ( 1984),

D. W. Griffith: An American Life

.

Cecil B. DeMille (1881-1959)

Cecil B. DeMille was born in Ashfield, Massachusetts, the son of a playwright and a

former actress. He tried his hand at both his parents' professions, without much success,

until two tyro producers, Jesse L. Lasky and Sam Goldfish (later Goldwyn), invited him

to direct a film. This was The Squaw Man ( 1914), the first American feature-length

movie and one of the first films to be made in the small rural township of Hollywood. A

thunderously old-fashioned melodrama, it was a huge hit. By the end of 1914 DeMille,

with five more pictures under his belt and hailed as one of the foremost young directors,

was supervising four separate units shooting one the Lasky lot, later to become

Paramount Studios.

DeMille's prodigious energy was matched, at this state, of his career, by an enthusiasm for

innovation. Though relying for his plots mainly on well-worn stage dramas by the likes of

Belasco or Booth Tarkington, he actively experimented with lighting, cutting, and framing

to extend narrative technique. The Cheat ( 1915), much admired in France (notably by

Marcel L'Herbier and Abel Gance), featured probably the first use of psychological

editing: cutting not between two simultaneous events but to show the drift of a character's

thoughts. 'So sensitive was DeMille's handling', observes Kevin Brownlow, 'that a

potentially foolish melodrama became a serious, bizarre and disturbing fable.'

The Whispering Chorus ( 1918) was even more avantgarde, its sombre, obsessive story

and shadowy lighting anticipating elements of film noir. But it was poorly received, as

was DeMille's first attempt at a grand historical spectacular, the Joan of Arc epic Joan the

Woman ( 1917). Aiming to recapture box-office popularity, DeMille changed course - for

the worse, some would say. 'As he lowered his sights to meet the lowest common

denominator,' Brownlow maintains, 'so the standard of his films plummeted.' With Old

Wives for New ( 1918) he embarked on a series of 'modern' sex comedies in which

alluring scenes of glamour and fast living - including, wherever possible, a coyly

titillating bath episode - were offset by a last-reel reaffirmation of traditional morality.

Box-office receipts soared, but DeMille's critical reputation took a dive from which it

never recovered.

This increasingly didactic post - preaching virtue, while giving audiences a good long

look at the wickedness of vice - found its logical outcome in DeMille's first biblical epic,

the $1m The Ten Commandments ( 1923). Despite misgivings at Paramount, now run by

the unsympathetic Adolph Zukor, the film was a huge success. Two years later DeMille

quit Paramount and set up his own company, Cinema Corporation of America, to make an

equally ambitious life of Christ, King of Kings ( 1927). This was an even bigger hit, but

CCA's other films flopped and the company folded. After a brief, unhappy stay at MGM

DeMille swallowed his dislike of Zukor and rejoined Paramount, at a fraction of his

former salary.

Cecil B. DeMille on set, c. 1928

To consolidate his position, DeMille shrewdly merged his two most successful formulas

to date, the religious epic and the sex comedy, in The Sign of the Cross ( 1932): opulent

debauchery on a lavish scale (with Claudette Colbert's Poppaea in the lushes bath

sceneyet) and a devout message to tie it all up. Critics sneered, but the public flocked.

When they stayed away from his next two films, both smaller-scale, modern dramas,

DeMille drew the moral: grandiose and historical was what paid off. From

Then on, in Charles Higham's view ( 1973), he abandoned the artistic aspirations which

had driven him as a young man. He would simply set out to be a supremely successful

film-maker.'

Cleopatra ( 1934) dispensed with religion, but made up for it with plenty of sex and some

powerfully staged battle scenes. With The Plainsman ( 1937) DeMille inaugurated a cycle

of early Americana, Leavening his evangelical message with the theme of Manifest

Destiny. The brassbound morality and galumphing narrative drive of films like Union

Pacific ( 1942) or Unconquered ( 1947) were calculated, Sumiko Higashi suggests, 'to

reaffirm audience belief in the nation's future, especially its destiny as a great commercial

power'.

The one-time innovator had now become defiantly oldfashioned. His last biblical epics,

Samson and Delilah ( 1949) and the remake of The Ten Commandments ( 1956) are lit

and staged as a series of pictorial tableaux with the director himself, where needed,

providing the voice of God. DeMille had always been known as an autocratic director; in

his later films the hierarchical principle informs the whole film-making process, casting

the audience in a subservient, childlike role. Yet audiences did not stay away. For all his

limitations, DeMille retained to the end the simple, compulsive appeal of the born

storyteller.

PHILIP KEMP

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

The Squaw Man ( 1914); The Virginian ( 1914); Joan the Woman ( 1917); The

Whisperting Chorus ( 1918); Old Wives for New ( 1918); The Affairs of Anatol ( 1921);

The Ten Commandments ( 1923); King of Kings ( 1927); The Sign of the Cross ( 1932);

Cleopatra ( 1934); The Plainsman ( 1937); Union Pacific ( 1939); Unconquered ( 1947);

Samson and Delilah ( 1949); The Greatest Show on Earth ( 1952); The Ten