The Oxford History of World Cinema (24 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

and experience that would make a technician attractive to Hollywood. Once the

acquisition had been made not only was the American industry inherently strengthened

but its most immediate competitors were proportionately weakened. The industry's

explanation for this policy was that it allowed producing companies to make products best

fitted for international consumption. For example, Hays talked about 'drawing into the

American art industry the talent of other nations in order to make it more truly universal',

and this explanation is not wholly fatuous. Whether or not it was the original intention

behind Hollywood's voracious programme of acquisition, the fact that the studios

contained many émigrés (predominantly European) probably allowed a more international

sensibility to inform the production process. Whatever the reasons, Hollywood's

particular achievement was to design a product that travelled well. Even considering the

studios' corporate might, without this factor American movies could not have become the

most powerful and pervasive cultural force in the world in the 1920s.

In addition to the explosion of film commerce that characterized the first three decades of

the century, the silent period was also marked by the widespread circulation of cinematic

ideas. No national cinematic style developed in isolation. Just as the Lumières'

apprentices carried the fundamentals of the art around the globe within a year, new

approaches to filmic expression continued to find their way abroad, whether or not they

were destined for widespread commercial release. The German and French industries may

not have been able to compete with the Americans abroad, but their products nevertheless

circulated in Europe, Japan, China, and many other markets. The Soviets professed their

admiration for Griffith even as they developed their theories of montage, while Mary

Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks were held spellbound by Eisenstein's Battleship

Potemkin ( 1925). By the time sound arrived, cinema all around the world was already

capable of speaking many languages.

Bibliography

Jarvie, Ian ( 1992), Hollywood's Overseas Campaign.

Thompson, Kristin ( 1985), Exporting Entertainment.

Vasey, Ruth ( 1995), Diplomatic Representations: The World According to Hollywood,

1919-1939.

Rudolph Valentio (1895-1926)

On 18 July 1926, the

Chicago Tribune

published an unsigned editorial that railed against

a pink powder machine supposedly placed in a men's washroom on Chicago's North Side.

Blame for 'this degeneration into effeminacy' was laid at the feet of a movie star then

appearing in the city to promote his latest film: Rudolph Velentino. The muscular star

challenged the anonymous author of the 'Pink Powder Puff' attack to a boxing match, but

the editor failed to show. Nevertheless, the matter would be settled, in a way, the

following month. On 23 August the 31-year-old star died at New York City's Polyclinic of

complications from an ulcer operation.

Following Valentino's unexpected death, the vitriolic response of American men to

Valentino was temporarily put aside as women, long regarded as the mainstay of the star's

fans, offered public proof of their devotion to the actor. The

New York Times

reported a

crowd of some 30,000, 'in large part women and girls,' who stood in the for hours to

glimpse the actor's body lying in state at Campbell's Funeral Church. These mourners

caused, noted the

Times

, 'rioting . . . without precedent in New York'. The funerary

hysteria, including reports of suicides, led the Vatican to issue a statement condemning

the 'Collective madness, incarnating the tragic comedy of a new fetishism'.

The tango from Rex Ingram's Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

Valentino was not the first star constructed to appeal to women; but in the years that

followed his death his impact on women would be inscribed as Hollywood legned. The

name of Rudolph Valentino remains one of the few from the Hollywood silent era that

still reverberates in the public imagination; a cult figure with an aura of exotic sexual

ambiguity. Valentino's masculinity had been held suspect in the 1920s because of his

former employment as a paid dancing companion, because of his sartorial excess, and

because of his apparent capitulation to a strong-willed life, the controversial dancer and

production designer Natasha Rambova. To many, Valentino seemed to epitomize the

dreaded possibilities of a 'woman-made' masculinity, much discussed and denounced in

anti-feminist tracts, general interest magazines, and popular novels of the time.

Valentino came to the United States from Italy in 1913 as a teenager. After becoming a

professional dancer in the cafés of New York City, he ventured out to California in 1917,

where he entered the movies in bit parts and graduated to playing the stereotype of the

villainous foreign seducer. Legend has it that June Mathis, an influential scriptwriter for

Metro, saw his film

Eyes of Youth

( 1919), and suggested him for the role of the doomed

playboy hero in Rex Ingram's production of The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse

( 1921). The film became a huge hit; by some reports it was Hollywood's biggest box-

office draw of the entire decade.

Through the films that followed Valentino came to represent, in the words of Adela

Rogers St Johns, 'the lure of the flesh', he male equivalent of the vamp. Valentino's exotic

ethnicity was deliberately exploited by Hollywood as the source of controversy, as was

the 'Vogue of Valentino' among women, discussed in the press as a direct threat to

American men. The hit movie The Sheik ( 1921) made Valentino a top star and sealed his

seductive image, but he was not satisfied with playing 'the sheikh' forever, and began to

demand different roles. After a sensitive performance in Blood and Sand ( 1922) and his

appearance in other, less memorable films (like Beyond the Rocks and Moran of the Lady

Letty, both 1922), Valentino was put on suspension by Famous Players-Lasky because of

his demand for control over his productions. During his absence from the screen,

Valentino adroitly proved his continuing popularity with a successful dance tour for

Mineralava facial clay. He returned to the screen in a meticulously produced costume

drama,

Monsieur Beaucaire

( 1924), in which he gives a wonderfully nuanced

performance as a duke who masquerades as a fake duke who masquerades as a barber.

Valentino's best performances, as in

Monsieur Beaucaire

and The Eagle ( 1925), stress his

comic talents and his ability to move expressively. These performances stand in contrast

to the clips that circulate of Valentino's work (especially from The Sheik) that suggest he

was an overactor whose brief career was sustained only by his beauty and the sexual

idolatry of female fans. However, the limited success of

Monsieur Beaucaire

outside

urban areas would prove (at least to the studio) that Madam Valentino's control over her

'henpecked' husband was a danger to box-office receipts. After a couple of disappointing

films and separation from his wife, a Valentino 'come-back' was offered with the expertly

designed and directed The Eagle, cleverly scripted by frequent Lubitsch collaborator Hans

Kräly. Ironically, Valentino's posthumously released last film, The Son of the Sheik,

would be a light-hearted parody of the vehicle that had first brought 'The Great Lover's to

fame only five years before.

GAYLYN STUDLAR

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

The Four Horsemen of the

Apocalypse ( 1921); The Sheik ( 1921); Blood and Sand ( 1922);

Monsieur Beaucaire

( 1924); The Eagle ( 1925); The Son of the Sheik ( 1926)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Hansen, Miriam ( 1991), Babel and Banylon.

Morris, Michael ( 1991), Madam Valentino.

Studlar, Gaylyn ( 1993), 'Valentino, "Optic Introxication" and Dance Madness'.

Walker, Alexander ( 1976), Valentino.

Joseph M. Schenck (1877-1961)

Among the figures who rose to power as Hollywood moguls during the studio period,

Joseph M. Schenck and his younger brother Nicholas had perhaps the most remarkable (if

chequered) careers. In their heyday the two brothers between them ran two major studios;

while Joe Schenck operated from behind the scenes as first the head of United Artists and

later that of Twentieth Century-Fox, Nick ran Loew's Inc. and its world famous

subsidiary, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Like most movie moguls, the Schencks were immigrants - in their case from Russia. They

came to the USA in 1892 and grew up in New York City, where they built up a successful

amusement park business. They prospered and in time merged with vaudeville act

supplier Loew's.

Nick Schenck rose to the presidency of Loew's, a position he held for a quarter of a

century. Joe, on the other hand, was more independent and struck out on his own. By the

early 1920s he had relocated to Hollywood and was managing the careers of Roscoe

(Fatty) Arbuckle, Buster Keaton, and the three Talmadge sisters.

Joe married Norma Talmadge in 1917 while Keaton married Natalie, and through the

1920s the Schenck-Keaton - Talmadge 'extended family' ranked at the top of the

Hollywood pantheon of celebrity and power. After his divorce in 1929 Schenck played

the role of the bachelor of Hollywood's golden era, acting as mentor to, and having

rumoured affairs with, stars from Merle Oberon to Marilyn Monroe.

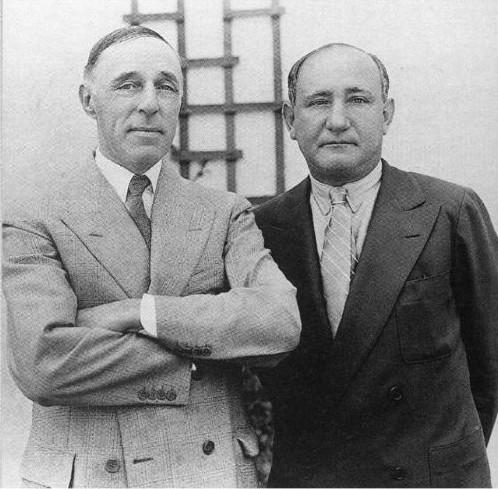

Joe Schenck (right) posing with D. W. Griffith before the making of Abraham Lincoln ( 1930)

Through the 1920s Joe Schenck formed a close association with United Artists, through

which many of the stars he managed distributed their films. He joined in November 1924

as president. Even as company head, however, he continued to work with the artists he

had sponsored, producing a number of their films, including Buster Keaton's The General

( 1927) and Steamboat Bill Jr. ( 1928)

In 1933 he created his own production company Twentieth Century Pictures, partnered

with Darryl F. Zanuck and backed financially by brother Nick at Loew's Inc. When

Twentieth Century merged with Fox two years later, Joe retained control, thanks again to

his brother's financial support. Thereafter, as Zanuck cranked out the pictures, Joe

Schenck worked behind the scenes, co-ordinating world-wide distribution and running

Twentieth Century-Fox's international chain of theatres.

Through the late 1930s Schenk and other studio heads (including brother Nick) paid

bribes to Willie Bioff of the projectionists' union to keep their theatres open. In time

government investigators unearthed this racketeering, and convicted Bioff. One movie

mogul had to go to gaol, to take the fall for the others. Convicted of perjury, Schenk spent

four months and five days in a federal prison in Danbury, Connecticut; in 1945 he was

pardoned and cleared on all charges by President Harry Truman.

The Schenk brothers hung on, through the bitter economic climate of the 1950s; through a

period where the methods that they had employed for nearly thirty years were mocked as

obsolete. With new audiences and new competition from television, the Schencks

ungracefully lost their positions of power. Ever the deal-maker, during the 1950s Schenck

and longtime friend Mike Todd signed up a widescreen process called Todd-AO, and