The Oxford History of World Cinema (43 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

exhaustive, in part because of the avantgarde's own insistence that film is a specific if

compound medium, whether basically 'photogenic' (as Epstein and others believed) or

'durational' (film was first defined as 'time-based' by Walter Ruttmann in 1919). The

modernist credo that art is a language brought the early avant-gardes close to Kuleshov

('the shot as a sign'), to Eisensteinian montage, and to Vertov's 'theory of intervals' in

which the gaps between shots -- like silences in post-serial music -- are equal in value to

the shots themselves.

Even the supposedly unified constructivist movement (itself made up of both rationalist

and spiritualist traits) included 'cinematology' (Malevich), the Dada-flavoured films of

Stefan and Franciszka Themerson (whose Adventures of a Good Citizen, made in Poland

in 1937, inspired Polanski's 1957 surreal skit Two Men and a Wardrobe), the abstract film

Black-Grey-White ( 1930) by László Moholy- Nagy as well as his later documentary

shorts (several, like a portrait of Lubetkin's London Zoo, made in England), the semiotic

film projects of the young Polish artist and political activist Mieczyslaw Szczuka and the

light-play experiments of the Bauhaus. For these and other artists filmmaking was an

additional activity to their work in other media.

FROM EUROPE TO THE USA

The inter-war period closes emblematically with Richter's exile from Nazi-occupied

Europe to the USA in 1940. Shortly before, he had completed his book

The Struggle for

the Film

, in which he had praised both the classic avantgarde as well as primitive cinema

and documentary film as opponents of mass cinema, seen as manipulative of its audience

if also shot through (despite itself) with new visual ideas. In the USA, Richter became

archivist and historian of the experimental cinema in which he had played a large role,

issuing (and re-editing, by most accounts) his own early films and Eggeling's. The famous

1946 San Francisco screenings, Art in Cinema, which he co-organized, brought together

the avant-garde classics with new films by Maya Deren, Sidney Peterson, Curtis

Harrington, and Kenneth Anger; an avant-garde renaissance at a time when the movement

was largely seen as obsolete.

Richter's influence on the new wave was limited but substantial. His own later films --

such as Dreams that Money can Buy ( 1944-7) -- were long undervalued as baroque

indulgences (with episodes directed by other exiles such as Man Ray, Duchamp, Léger,

and Max Ernst) by contrast to the 'pure' -- and to a later generation more 'materialist'

-abstract films of the 1920s. Regarded at the time as 'archaic',

Dreams

now seems

uncannily prescient of a contemporary post-modernist sensibility. David Lynch selected

extracts from it, along with films by Vertov and Cocteau, for his 1986 BBC

Arena

film

survey. Stylish key episodes include Duchamp's reworking of his spiral films and early

paintings, themselves derived from cubism and chronophotography, with sound by John

Cage. Man Ray contributes a playful skit on the act of viewing, in which a semi-

hypnotized audience obeys increasingly absurd commands issued by the film they

supposedly watch. Ernst's episode eroticizes the face and body in extreme close-up and

rich colour, looking ahead to today's 'cinema of the body' in experimental film and video.

Richter's own classes in film-making were attended by, among others, another recent

immigrant Jonas Mekas, soon to be the energetic magus of the 'New American Cinema'.

Two decades earlier, the avant-garde had time-shifted cubism and Dada into film history

(both movements were essentially over by the time artists were able to make their own

films). By the 1940s, a new avant-garde again performed a complex, overlapping loop,

reasserting internationalism and experimentation, at a time as vital for transatlantic art as

early modernism had been for Richter's generation. Perhaps the key difference, as P.

Adams Sitney argues, is that the first avant-garde had added film to the potential and

traditional media at an artist's disposal, while new American (and soon European)

filmmakers after the Second World War began to see filmmaking more exclusively as an

art form that could exist in its own right, so that the artist-film-maker could produce a

body of work in that medium alone. Ironically, this generation also reinvented the silent

film, defying the rise of naturalistic sound which had in part doomed its avantgarde

ancestors in the 'poetic cinema' a decade before.

Bibliography

Curtis, David ( 1971),

Experimental Cinema

.

Drummond, Phillip, Dusinberre, Deke, and Rees, A. L. (eds.) ( 1979),

Film as Film

.

Hammond, Paul ( 1991),

The Shadow and its Shadow

.

Kuenzli, Rudolf E. (ed.) ( 1987),

Dada and Surrealist Film.

Lawdor, Standish ( 1975),

The Cubist Cinema

.

Richter, Hans ( 1986),

The Struggle for the Film

.

Sitney, P. Adams ( 1974),

Visionary Film

.

Carl Theodor Dryer (1889-1968)

The illegitimate son of a maid and a factory-owner from Sweden, Dreyer was born and

brought up in Copenhagen, where his adoptive family subjected him to a miserable and

loveless childhood. To earn a living as soon as possible, he found work as theatre critic

and air correspondent for a Danish newspaper. He also began to write film scripts, the

first of which was made into a film in 1912. The following year he began an

apprenticeship at Nordisk, for whom he worked in various capacities and wrote some

twenty scripts. In 1919 he directed his first film, The President

(Præsidenten),

a

melodrama with a rather clotted Griffithian narrative structure which nevertheless showed

a strong visual sense. This was followed by the striking Leaves from Satan's Book

(Blade

of Satans bog),

an episode film partly modelled on Intolerance, shot in 1919 but not

released until 1921. The young Dreyer proved to be something of a perfectionist in

matters of

mise en scène

and in the choice and direction of actors. This provoked a break

with Nordisk and the director embarked on a independent career which led him to make

his remaining silent films in five different countries. The Parson's Widow (

Prästänkan

,

1920) was shot in Norway for Svensk Filmindustri. While owing a stylistic debt to

Sjöström and Stiller, it shows a marked preference for character analysis at the expense of

narrative development. This impression is confirmed by Mikael, made in Germany in

1924, the story of an emotional triangle linking a painter, his male model, and a Russian

noblewoman who seduces the boy away from the master, depriving him of his inspiration.

Although heavy with symbolist overtones (derived in large part from the original novel by

Hermann Bang), Mikael represents Dreyer's first real attempt to analyse the inner life of

characters in relation to their environment.

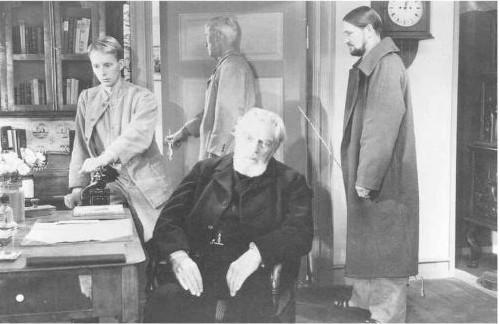

Ordet

( 1955)

Dreyer fell out with Erich Pommer, the producer of Mikael, and returned to Denmark

where he made Master of the House (

Du skal ære din hustru,

1925), a drama about a

father whose egotistical and authoritarian behaviour wreaks terror on his wife and

children. Here the closeups on faces take on a crucial role. 'The human face', Dreyer

wrote, 'is a land one can never tire of exploring There is no greater experience in a studio

than to witness the expression of a sensitive face under the mysterious power of

inspiration.' This idea is the key to The Passion of Joan of Arc (

La Passion de Jeanne

d'Arc

, 1928), in which the close-up reaches its apotheosis in the long sustained sequence

of Joan's interrogation against a menacing architectural backdrop-all the more oppressive

for seeming to lack precise spatial location.

Dyeyer's last silent film, Joan of Arc was shot in France with massive technical and

financial resources and in conditions of great creative freedom. It was instantly acclaimed

by the critics as a masterpiece. But it was a commercial disaster, and for the next forty

years Dreyer was only able to direct five more feature films. Vampyr ( 1932) fared even

worse at the box office. Using only non-professional actors, Vampyr is one of the most

disturbing horror films ever made, with a hallucinatory and dreamlike visionary quality

intensified by a misty and elusive photographic style. But it was badly received, and

Dreyer found himself at the height of his powers with the reputation of being a tiresome

perfectionist despot whose every project was a failure.

Over the next ten years Dreyer worked on abortive projects in France, Britain, and

Somalia, before returning to his former career as a journalist in Denmark. Finally, in

1943, he was able to direct Day of Wrath

(Vredens dag)

, a powerful statement on faith,

superstition and religious intolerance. Day of Wrath is stark and restrained, its style

pushing towards abstraction, enhanced by high-contrast photography. Danish critics saw

in the film a reference to Nazi persecution of the Jews, and the director was persuaded to

escape to Sweden. When the war was over, he returned to Copenhagen, scraping together

enough money from running a cinema to be able to finance The Word

(Ordet

, 1955) the

story of a feud between two families belonging to different religious sects, interlaced with

a love story between members of the opposing families.

Ordet

takes even further the

tendency towards simple and severe decors and mise en scène, intensified by the use of

long, slow takes. Even more extreme is Gertrud ( 1964), a portrait of a woman who

aspires to an ideal notion of love which she cannot find with her husband or either of her

two lovers, leading her to renounce sexual love in favour of asceticism and celibacy.

While the restrained classicism of

Ordet

won it a Golden Lion at the Venice Festival in

1955, the intransigence of Gertrud, with its static takes in which neither the camera not

the actors seem to move at all for long periods, was found excessive by the majority of

critics. A storm of abuse greeted what deserved to be seen as Dreyer's artistic testament, a

work of distilled and solemn contemplation. Dreyer continues to be admired for his visual

style, which, despite surface dissimilarities, is recognized as having a basic internal unity

and consistency, but the thematic coherence of his work-around issues of the unequal

struggle of women and the innocent against repression and social intolerance, the

inescapability of fate and death, the power of evil in earthly life-is less widely

appreciated. His last project was for a Life of Christ, in which he hoped to achieve a

synthesis of all stylistic and thematic concerns. He died shortly after he had succeeded in

raising the finance from the Danish government and Italian state television for this

project, on which he had been working for twenty years.

PAOLO CHERCHI USAI

SELECT FILMOGRAPHY

Præsidenten (The President)

( 1919); Prästänkan (The Parson's Widow) ( 1920); Blade af Satans bog (Leaves from

Satan's Book) ( 1921); Die Gezeichneten (Love One Another) ( 1922); Der var engang

(Once upon a Time) ( 1922); Mikael (Michael / Chained / Heart's Desire / The Invert)

( 1924); Du skal ære din hustru (The Master of the House) ( 1925); Glomdalsbruden (The

Bride of Glomdale) ( 1926); La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (The Passion of Joan of Arc)

( 1928); Vampyr der Traum des Allan Gray (Vampyr / Vampire) ( 1932); Vredens dag

(Day of Wrath) ( 1943); Tvä Människor (Two People) ( 1945); Ordet (The Word) ( 1955);

Gertrud ( 1964)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bordwell, David ( 1981),

The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer

.

Drouzy, Maurice ( 1982),

Carl Th. Dreyer né Nilsson.

Monty, lb ( 1965),

Portrait of Carl Theodor Dreyer.

Sarris, Andrew (ed.) ( 1967),

Interviews with Film Directors.

.

Schrader, Paul ( 1972),

Transcendental Style in Film.

Serials

BEN SINGER