The Oxford History of World Cinema (55 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

International Exclusives, can fairly be described as primitive -- whether in terms of its

cheap and poorly designed backdrops, its wooden acting, or a mode of narrative

construction that makes minimal use of continuity editing. It is mainly the film's length

(seven reels), that distinguishes it from films produced a decade before.

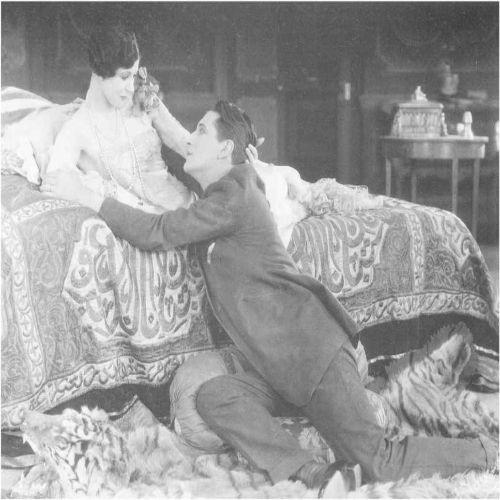

Ivor Novello and Mae Marsh in The Rat ( 1925), the story of a Parisian jewel thief,

directed by Graham Cutts and produced by Michael Balcon

THE 1920S: A NEW GENERATION

By the mid- 1920s most of the pre-war production companies had gone out of business,

and with them such 'pioneers' as Cecil Hepworth. A new generation of pro ducers or

producer-directors entered the industry during this period. Both Michael Balcon

(producer) and Herbert Wilcox (producer-director) adopted similar strategies to develop

the indigenous industry. One such strategy was the importation of Hollywood stars. This

was not a total novelty, but in the past it had met with only limited success. However,

Wilcox successfully utilized the talents of Dorothy Gish, and in doing so also established

a deal with Paramount. More important was the development of co-production

agreements by both Balcon and Wilcox, and other British producers. Co-productions,

particularly with Germany but also with other countries such as Holland, would become a

significant factor in the development of the British film industry in the mid- and late

1920s. It was as a result of this practice that the young Alfred Hitchcock acquired

experience of German production methods when he was sent to work at the Ufa studios in

Neubabelsberg early on in his career with Gainsborough.

For Herbert Wilcox, the agreements he signed with Ufa were important not only as a way

of opening up the market but also because the contracts gave him access to the tates.

However, this success was in large part attributable to spectacle (adequately financed) and

the sexual dynamic of the narrative; but Wilcox, unlike Hitchcock and some other young

directors, seems to have learnt little from the encounter with German cinema, and, from

the perspective of film form, Decameron Nights is a film still marked by the relatively

long scale of most of its shots and a general lack of scene dissection.

Michael Balcon was an important figure in the British film industry for a number of

reasons. Although he produced only a relatively small number of films in the 1920s, most

of them, including The Rat ( Gainsborough, 1925), were big commercial successes.

Further, Balcon's career was a clear signpost to that division of labour that came rather

late in the British film industry: that is, between producing and directing. Balcon was a

producer, rather than a producer-director, and it was only the separation of these roles that

allowed the development of skills specifically associated with each function.

Although in the context of British culture film-making was generally. held in low esteem,

a number of university graduates were to enter the film industry towards the end of this

period, including Anthony Asquith, the son of the Liberal Prime Minister. Asquith had not

only developed a considerable knowledge of European cinema during his university days,

but his privileged background enabled him to meet many Hollywood stars and directors

during his visits to the United States. The importance of these factors became evident

when he began his film career. On Shooting Stars (British Instructional Films, 1928)

Asquith was assistant director, but he had also written the screenplay, and was involved

with the editing of the film. Shooting Stars was self-reflexive, in so far as it was a film

about the film industry, film-making, and stars, although the reference was more to

Hollywood than England, with Brian Aherne featuring as a Western genre hero. The

lighting (by Karl Fischer), the use of a variety of camera angles, and the rapid editing of

some sequences linked the film more to a German mode of expression. These elements,

combined with the fact that the screenplay was not developed from a West End theatre

production, unlike so many British productions in the 1920s, produced a film that was

pure cinema.

By the end of the 1920s the British film industry was transformed. The shift to vertical

integration established a stronger industrial base, and, despite its negative aspects, the

protective legislation introduced in 1927 did also lead to an expansion of the industry. The

new generation who entered the industry in the mid-1920s had a greater knowledge and

understanding of developments taking place in both European cinema and Hollywood,

and this was also to play its part in the transformation of the British cinema, making it

better prepared to face the introduction of sound at the end of the decade.

Bibliography

Hepworth, Cecil ( 1951), Came the Dawn: Memories of a Film Pioneer.

Low, Rachael ( 1949), The History of the British Film, ii: 1906-1914.

--- ( 1950), The History of the British Film, iii: 1914-18.

--- ( 1971), The History of the British Film, iv: 1918-29.

--- and Manvell, Roger ( 1948), The History of the British Film, i: 18961906.

Pearson, George ( 1957), Flashback: The Autobiography of a British Filmmaker.

Sadoul, Georges ( 1951), Histoire générale du cinéma, vol. iii.

Salt, Barry ( 1992), Film Style and Technology.

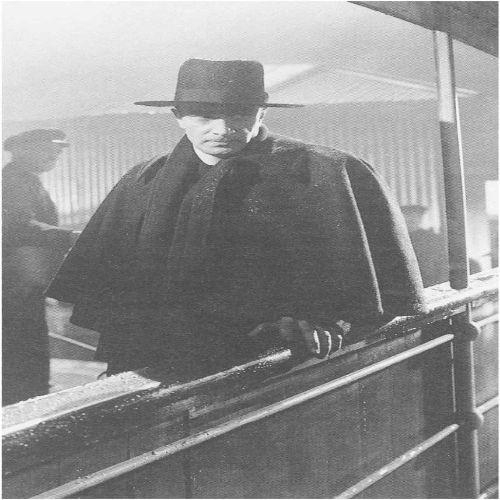

Conrad Veidt (1893-1943)

Conrad Veidt as the German Lieutenant Hart in Michael Powell 's The Spy in Black

( 1939)

Conrad Veidt started his career in 1913, at Max Reinhardt's acting school. After a short

period of employment in the First World War as a member of different front theatre

ensembles, he returned to the Deutsches Theater Berlin, and then, in 1916, began working

in the movies. In 1919, in the first homosexual role on screen in Anders als die Andern,

and above all as the somnambulist Cesare in Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, he created an

expressionist acting style that made him an international star. In the early 1920s he starred

in several of Richard Os wald 's Sittenfilme dealing with sexual enlightenment, and went

on to work with many of the best-known directors of the time. Veidt moved to the USA in

the second half of the decade, but returned to Germany on the introduction of sound,

starring in some of the early Ufa sound successes and their English versions. In 1932

Veidt started work in Britain, shooting a pro-Semitic version of Jew Suss ( 1934) and the

more equivocal Wandering Jew ( 1933), after which he became persona non grata in Nazi

Germany. With his Jewish wife Lily Preger he remained in London, gaining British

citizenship in 1939. He continued to work, incarnating Prussian officers for Victor Saville

and Michael Powell. In 1940 he moved to Hollywood, where he was cast mainly as a

Nazi - most famously, Major Strasser in Casablanca ( 1942).From figures reach beyond

the scope of the familiar scoundrel cliché. His characters are burdened with the

knowledge that they are doomed, and so have an introverted and stoic edge, accepting

their fate and never compromising in order to save their own lives. They always remain

true to their mission and often border on the fanatical in their sense of duty and singleness

of vision. However, Veidt's characters are also enveloped in an aura of melancholy which

is made distinguished by their good manners and cosmopolitan elegance. Veidt's face

reveals much of the inner life of his characters. The play of muscles beneath the taut skin,

the lips pressed together, a vein on his temple visibly protruding, nostrils flaring in

concentration and self-discipline. These physical aspects characterize the artists,

sovereigns, and strangers of the German silent films, as well as the Prussian officers of

the British and Hollywood periods.The intensity of Veidt's facial expressions is supported

by the modulation of his voice and his clear articulation. His tongue and his slightly

irregular teeth become visible when he speaks, details which allow his words to flow

carefully seasoned from his wide mouth - in contrast to the slang-like mutterings of

Humphrey Bogart who played opposite him in two US productions of the 1940s. Veidt's

German accent is a failing which he turns into a strength; it becomes the means of

structuring the flow of speech. The voice, which can take on every nuance from an

ingratiating whisper to a barking command, is surprising in its abrupt changes in tone.

Once heard, it is easy to imagine the voices of his silent film characters. Veidt's late film

roles reflect back on the early silent ones, enriching them retrospectively with a sound-

track.DANIELA SANNWALDSELECT FILMOGRAPHY (with directors) Der Weg des

Todes ( Robert Reinert, 1916-17); Anders als die Andern ( Richard Oswald, 1918-19);

Das Cabinet des Dr Cattgari ( 1919-20); Das indische Grabmal ( Joe May, 1921); Die

Brûder Schellenberg ( Karl Grune, 1925); Der Student von Prag ( Henrik Galeen , 1926);

The Man who Laughs (USA, Paul Leni, 1927); Die letzte Kompagnie ( Kurt Bernhardt,

1929); Der Kongress tanzt ( Erik Charell, 1931); Jew Süss ( Lothar Mendes, 1934); The

Spy in Black ( Michael Powell, 1939); Casablanca ( Michael Curtiz, 1942); Above

Suspicion ( Richard Thorpe, 1943)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Allen, Jerry C. ( 1987), From Caligari to Casablanca.

Jacobsen, Wolfgang (ed.) ( 1993), Conrad Veidt: Lebensbilder.

Sannwald, Daniela ( 1993), "Continental Stranger: Conrad Veidt und seine britischen

Filme".

Germany: The Weimar Years

THOMAS ELSAESSER

'German Cinema' recalls the 1920s, Expressionism, Weimar culture, and a time when

Berlin was the cultural centre of Europe. For film historians, this period is sandwiched

between the pioneering work of American directors like D. W. Griffith, Ralph Ince, Cecil

B. DeMille, and Maurice Tourneur in the 1910s, and the Soviet montage cinema of Sergei

Eisenstein, Dziga Vertov, Vsevolod Pudovkin in the late 1920s. The names of Ernst

Lubitsch, Robert Wiene, Paul Leni, Fritz Lang, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, and Georg

Wilhelm Pabst stand, in this view, for one of the 'golden ages' of world cinema, helping-

between 1918 and 1928-to make motion pictures an artistic and avantgarde medium.

Arguably, such a view of film history is no longer unchallenged, yet surprisingly many of

the German films from this period are part of the canon: The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Das

Cabinet des Dr. Caligari, Robert Wiene, 1919), The Golem (Der Golem, wie er in die Welt

karo, Paul Wegener, 1920), Destiny (Der müde Tod, Fritz Lang, 1921), Nosferatu ( F. W.

Murnau , 1921), Dr Mabuse ( Lang, 1922), Waxworks (Das Wachsfigurenkabinett, 1924),

The Last Laugh (Der letzte Mann, Murnau, 1924), Metropolis ( Lang, 1925), Pandora's

Box (Die Biichse der Pandora, G. W. Pabst, 1928). Even more surprisingly, they have also

entered popular movie mythology and now live on, parodied, pastiched, and recycled, in

very different guises, from pulp movies to post-modern videoclips. In their time, the films

were associated with German Expressionism, mainly because of their self-conscious

stylization of décor, gesture, and lighting. Others regarded the same pre-eminence of

stylization, fantasy, and nightmare visions as evidence of the inner torment and moral

dilemmas in those for whom the films were made. Equivocation was not confined to the

films: did the films reflect the political chaos of the Weimar Republic, or did the parade of