The Pacific (32 page)

Authors: Hugh Ambrose

Tags: #United States, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Pacific Area, #Pacific Area, #Military Personal Narratives, #World War; 1939-1945, #Military - World War II, #History - Military, #General, #Campaigns, #Marine Corps, #Marines - United States, #World War II, #World War II - East Asia, #United States., #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Military - United States, #Marines, #War, #Biography, #History

The next morning the team set off in better spirits with the prospect of exiting the swamp. The water receded somewhat by noon and they waded ashore at about two p.m. In an hour, they found the railway line that was the trail to Longa-og. The infantry training of the marines took control. A scouting party was sent up the trail to the village, an OP was maintained at the spot they had met the track; the rest of the party pulled back five hundred yards and waited. The scouts returned at dark after a hike of three kilometers. They had found some deserted shacks and evidence of a large unit of enemy troops having visited very recently. Were the Japanese farther up the track, the escapees wondered, or had they returned to Davao? As that was discussed, the team inventoried their food supply. Although each man had consumed only his daily allotment--one twelve- ounce can of sardines or corned beef--they had not planned on getting lost. Food was short.

In some ways, the decision of what to do next was made for them. They could not stay there because they had only a few rations left. They could not wade back into the jungle in any direction. Taking the road to the right led them to Davao. Tired and scared men, though, come to agreements slowly. The marines suggested moving out in a tactical formation: the two groups of five men would leapfrog each other. One would be safe in the bush while the other hiked down the track. With a plan for the morning, they began preparing a place to sleep above the silent predators on the forest floor.

The next morning they skipped breakfast and set off in patrol formation, one group leapfrogging the other, up the railroad track. Four kilometers up the track they came to the scene of a firefight. Empty cartridge cases, dried blood, cigarette butts, and hardtack littered the railroad tracks. About five hundred yards farther, they came to a hamlet. Chickens, dogs, and other domesticated animals ran amok, but the inhabitants had fled. Some of the huts, with a roof made of nipa and walls of bamboo, had been set afire in the last day or two. After posting guards, the team went into one of the huts to cook some food in the sandbox. One of the lookouts returned within moments, reporting that he had heard a metallic click. He had whirled around to catch sight of two armed Filipinos in the bushes near the railroad. The Filipinos, upon being seen, had fled in the direction of Longa- og.

Those men may have been guerrillas, but they might also have been guides for the enemy. The team agreed they must move quickly for Longa-og. They had to make contact with the guerrilla forces. The railroad was the only path. Packing up the uncooked food, they set off. They hiked ten kilometers, reaching the village about three p.m. The villagers conducted them to a specific spot and stepped away. They heard a voice shouting in a foreign language and they all dropped to the ground. More yelling caused some of the team to yell back, until one voice rang out clearly: "You're surrounded! Surrender!"

Aside from a few bolo knives, they had no weapons. They held up their arms in surrender. A whistle sounded and fifty armed men stepped out of the bushes. The Filipino guerrillas searched them for weapons. "We told them we were Americans." The hostility did not abate. Ben and Victor, however, slipped into their native tongue and the situation changed quickly. The guerrillas began to believe that Shifty and the others were not spies of some kind. While told how the team had come to the village, however, the guerrilla leader expressed surprise that they had survived the swamp. No locals ever went through it. It teemed with crocodiles.

The Americans told the leader about seeing two armed Filipinos near the railroad. Those men worked for him, the guerrilla replied; they had fired at men they assumed were IJA. "However, the ammunition was faulty and the rifle did not fire." No apology followed. The guerrilla leader at last accepted their identity and introduced himself as Casiano de Juan, captain of the barrio and leader of the local guerrillas. In their brief conversation with him, the escapees nicknamed Casiano "Big Boy." Soon the guerrillas and the escapees all walked back into the village of Longa-og as compatriots.

The villagers welcomed them as friends. The Filipinos' generosity overwhelmed the escapees. Great quantities of fruit, meat, eggs, and more were proffered and gratefully accepted. Big Boy brought them to the barrio's meetinghouse. Other villagers removed the fighting gamecocks that lived there. In the evening, the Filipinos held a feast for the Americans. The escapees got to know Big Boy, who was a sergeant in the Mindanao guerrillas and had escaped from the enemy several times. The emperor had a reward on his head. The Americans had witnessed his toughness; now they saw in him the personification of the Filipino personality: easygoing, warm, kind. For the feast the villagers served the local delicacy, balut. To make balut, the villagers left an egg under a chicken for twenty days, then boiled it. Half formed, the embryo's feathers and beak could be recognized in the goo. The locals bit down on the beaks, which "popped like popcorn," and ate quickly. The Americans knew enough not to slight the honor being paid them. Shifty bit down on one, grinned, and said, "Good."

The carabao steaks went down easier. Resembling a water buffalo, the carabao provided plenty of savory meat. Over the next few days, the men ate every few hours, rested, and washed themselves. In his diary, Shifty described the dishes served at every fabulous meal. All the villagers hated the Japanese and loved Americans. Shifty met a boy who had had the first two fingers on his right hand cut off by the Japanese to prevent him from firing a rifle. At Big Boy's hut they enjoyed drinking tuba, the first alcohol they had tasted in a long time. He told them he would bring them to his superiors when he had made arrangements. He also told them of a radio on Mindanao that communicated with Australia. That got their attention. The group began to discuss changing their plans in light of this dramatic news. They might just make it home after all. As much as the news excited Shifty, he took a few days to relax. Lying in the hut and listening to the rain drum on the roof gave him a deep sense of peace. He slept soundly.

Supplied by the good people of Longa-og, the Americans began the journey to the home of Dr. David Kapangagan, an evacuee from Davao City who could connect them to the guerrilla movement. At every stop along the way, the villagers welcomed them, feted them with music and feasts, let them sleep in their beds. The relaxed and fun life continued at Dr. Kapangagan's house, where they waited for a few days. One night ten or twelve very pretty girls came to invite them to a dance. The Americans walked in the torch parade to the dance, watched the locals perform, and even returned the favor by singing a song. Shifty found himself "called on to do the Tennessee Stomp."

On April 17, Captain Claro Laureta of the Philippine Constabulary arrived. He affirmed the existence of a large guerrilla force on the northern coast of Mindanao--his constabulary was a part of it--but he refused to confirm the report about the radio communication with Australia. The team listened intently, probing for more answers about the guerrillas, their whereabouts, leadership, goals, and the journey. The trek to the northern coast would take them through a remote area controlled by tribes of Atas and Honobos."After a meeting all the party decided to change plans and go to the guerrilla headquarters on Northern Mindanao." Captain Laureta organized food for their long journey and guides. On April 21, they set off on the long trek north.

AFFECTION FOR THE SB2C DID NOT GROW ON THE PILOTS OF BOMBING SIX. The manufacturer had suggested the nickname "Helldiver." Its pilots, however, preferred to call it the Beast. It required a lot of attention in level flight and real concentration when landing because of its shaky hold on the air. As part of his April fitness reports, Ray Davis (now a lieutenant commander) asked Lieutenant Micheel to state his preferred duty. Mike said he would prefer to become a fighter pilot on a carrier in the Pacific. He wanted out of El Centro, a backwater training base, and in to the navy's new fighter plane, the Hellcat, which had earned rave reviews. Neither Davis nor apparently the U.S. Navy evinced any interest in letting a skilled dive- bomber pilot get away. In mid-April Bombing Six cut its training schedule short and flew east.

They stopped in Columbus, Ohio, and let the technicians of the Curtiss-Wright check their planes. Mike arrived three days late because of engine trouble. Once the factory engineers gave his plane, number 00080, the all clear, he set out to catch up with his squadron, but ran out of gas and lost two days. He landed at NAS Norfolk, part of the navy's vast complex there, on April 22, well behind the rest of his squadron. The new pilots in Bombing Six had already begun to enjoy an advantage he had not had a year before: practicing carrier landings on a flattop out in the Chesapeake Bay in advance of landing upon their new fleet carrier.

After its new pilots qualified as carrier pilots on a small "jeep" carrier in Chesapeake Bay, Bombing Six landed their SB2Cs aboard the new fleet carrier, USS

Yorktown,

on May 5.

12

Yorktown

had been commissioned two weeks earlier. Her name recalled the carrier lost at Midway as well as ships dating back to the dawn of the United States Naval Service. The pilots found her passageways crowded with workers and tradesmen of all kinds, completing the installation of the furnishings, fittings and equipment.

Of course she was bigger, the new

Yorktown

. Although not as large as

Saratoga

,

Yorktown

's flight deck beat

Enterprise

's by about eighteen feet in length. The longer airstrip pleased Mike, who had always "puckered" at takeoffs more than most. Bombing Six had joined Air Group Five, including thirty-six Hellcats, a scouting squadron that also flew the SB2C and brought the total number of Beasts on board to thirty-six, and eighteen Avengers, the navy's torpedo plane. Jimmy Flatley, one of the most respected fighter pilots of the war, commanded the carrier's air group. His squadrons began practicing their landings on their new carrier as she steamed up and down Chesapeake Bay, preparing for her shakedown cruise.

WHEN SID WAS RELEASED FROM THE HOSPITAL, HE RETURNED TO FIND HIS battalion had left for field exercises. The 2/1 returned a few days later and, when the men of #4 gun squad caught sight of him, they expressed their disappointment that he hadn't died. Sid smiled. Deacon and W.O. shared stories of long marches, extended order drills, and gunnery practice, so Sid was glad he had missed it. Conditioning hikes, though, became a common morning duty, with Lieutenant Benson leading his mortar platoon around and around the Fitzroy Gardens, a beautiful park near the cricket grounds.

The mortar platoon usually had the afternoon off, with long liberties on weekends. Deacon and Sid often went to tea with the Osborne family. One afternoon, though, Sid met up with one of the new guys in the squad, Tex. They took the tram to Young & Jackson, a large pub across the street from the main railway station at the center of town. The pub boasted a painting of a nude young woman named Chloe. While taking a good look at Chloe, Sid drank a pint of beer. Tex downed three scotch and waters. The two walked down the street to another pub. Sid sipped a beer and Tex poured in three drinks. They walked out on the street. Six American sailors were crossing the street toward them. "Tex spread his arms and told them to stop right where they were and get back on the other side of the street because this side of the street belonged to us." Tex threatened to swab the deck with them. Horrified, Sid tried to look mean. The sailors decided to skip this fight. "Are you trying to get us killed?" Sid asked.

"I can tell which sailors would and would not fight," said Tex. He had a head full of steam as he walked up the street. Sid "let Tex go ahead without me shortly. Why fight unnecessary skirmishes in a long war?"

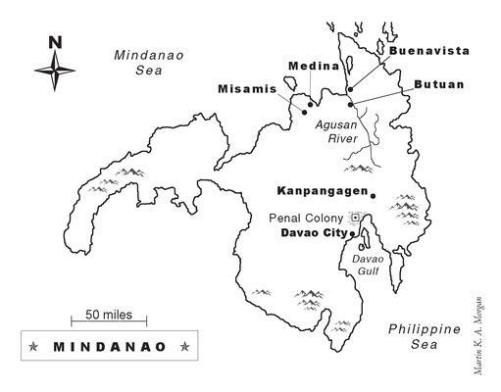

"WE WERE," SHIFTY GUESSED, "THE FIRST WHITE PEOPLE TO USE THIS TRAIL." THE hike over the mountains on a trail he could not always see followed a few days paddling in a dugout canoe. While the Americans labored, quickly coming to the last of their strength, the Filipinos carried all of the supplies up the slopes with ease. Their encounters with "bushy- headed" people armed with spears, shields, bows and poison-tipped arrows went well. On the far side of the mountains, they bade farewell to most of their guides, climbed into boats, and began floating down the Agusan River toward the northern coast.

The cities of the northern coast of Mindanao, like Butuan and Buenavista, had large guerrilla presences, but also IJA garrisons. The carefree life of the backcountry gave way to vigilance. On May 5, the team arrived in Medina and was guided to Lieutenant Colonel Ernest McClish, an officer in the U.S. Army before the war and now commander of 110th Division, Tenth Military District of the Mindanao guerrilla force. Colonel McClish took them to the home of Governor Panaez, the "Coconut King of the Philippines," for dinner. They sat down at a table with silver-ware, tablecloths, napkins, and a meal as good as anything in the United States. An eleven-piece orchestra serenaded them. After dinner, McClish gave Shifty a cigar.