The Pacific (40 page)

Authors: Hugh Ambrose

Tags: #United States, #World War; 1939-1945 - Campaigns - Pacific Area, #Pacific Area, #Military Personal Narratives, #World War; 1939-1945, #Military - World War II, #History - Military, #General, #Campaigns, #Marine Corps, #Marines - United States, #World War II, #World War II - East Asia, #United States., #Biography & Autobiography, #Military, #Military - United States, #Marines, #War, #Biography, #History

In the week after the Basilone Day parade, the reporters from

Life

magazine and other news outlets wanted more from the man himself. While asking him about his days as a golf caddie, they uncovered an interesting connection. John told them that he had carried bags for wealthy and influential Japanese businessmen. Manila recalled, " The Japs always carried and used cameras while on the course, which has a wonderful view of the surrounding factories, railroads and canals. They never failed to smile politely and make room for other, faster players coming through."

137

Their behavior had seemed odd to him at the time; now it seemed treasonous.

Even back in the mid- 1930s he had "smelled a fight coming" and joined the army. After his hitch was up, he decided "the army's not tough enough for me." The reporters and photographers studied the tattoos he'd acquired while in the army in great detail. "As mementos of his first enlistment he had two fine, large, lush tattoos, one on each arm," one reporter later wrote. " The right upper arm shows, in delicate modulations of blue and red inks, the head and shoulders of a full-blown Wild West girl. The left arm, in equally bold markings, bears a sword plunged into a human heart, the whole entwined with stars and flowers and a ribbon on which is written, 'Death Before Dishonor.' "

138

The interviews allowed John to dispel one of the false stories that his own family had begun. Back in June, the Basilones had told reporters that Manila John "held several Army boxing championships."

139

When asked for details, John said he had tried boxing as a middleweight in the Golden Gloves program, but he had not been "particularly successful."

140

The matter dropped. When a reporter asked him later what he intended to do with his $5,000 war bond, he replied, "When the right girl comes along I'm going to buy a ten room house, and I'm going to have a bambino for each room."

141

Of course, the reporters eventually got around to discussing the night of October 24. John had not learned to elaborate much on it. Sometimes he would admit that he had been scared he wouldn't make it, like when he ran the hundred-yard dash for more belts of ammunition. At other moments, he'd insist, "I wasn't scared--didn't have time to be. Besides, I had my men to worry about. If you don't keep a cool head, you won't have any head to worry about."

142

He made clear that "the next day, the japs fell back," without directly stating that his battle had not lasted three days as previously reported.

When pushed by the writer James Golden over the course of a four- day interview "to talk about himself and his heroics," John said: "Look, Golden, forget about my part. There was not a man on the canal that night who doesn't own a piece of that medal awarded me."

143

The blunt assertion did not stop the writer from pushing harder to get the story. After all, Golden figured, John must have done something extraordinary to win the Medal of Honor. Golden eventually concluded that John was "simply . . . too modest." Manila John had not even known what exactly he had done to merit the Medal of Honor until he read the medal citation signed by Roosevelt months later. Golden talked John into pulling out his old set of blues and wearing them with his medal hung around his neck for a photo. When Golden's article appeared, it repeated the same story as the others, describing Manila John as "a man-sized marine."

144

The big interviews with

Life

and

Parade

and the meetings with the local industries completed, John prepared to travel around to other factories on the Navy Incentive Tour. Before setting off, John sent a note to J.P., Greer, and his friends in Dog Company.

145

He wrote them about the morning in D.C. when a corporal had walked into his room and inquired, "Sergeant Basilone, would you like to get up this morning?"

146

John knew his buddies would howl over that one. Manila also convinced his sister Mary to write a letter to Greer's family to let them know some news about their son Richard.

147

He had not forgotten the promise he had made to Greer back in Australia. On September 27, he traveled back to the navy's office in Manhattan and reported in to the Inspector of Naval Material.

ON SEPTEMBER 27, LIEUTENANT BENSON ORDERED HIS PLATOON OF 81MM mortarmen to pack their gear. They were boarding ship that night. No one in the #4 gun squad was surprised; they had been preparing for weeks. The news that the 1st Marine Division also had been transferred to General MacArthur's command for its next operation, however, came like a thunderclap. Barks of derision followed Benson's announcement. Army fatigue hats were issued. Sid threw the hat away and boarded the truck. The 2/1 arrived at Queen's Pier in downtown Melbourne at five thirty p.m. Their gear did not arrive until eleven p.m. Sid and Deacon went on a working party, of course, until the wee hours. The next day brought more of the same as they loaded their ship, one of the navy's new troop transports called a Liberty Ship. The good news came at the end of the day, when all hands got liberty. The veterans of Guadalcanal had a very clear expectation of what awaited them and therefore made the most of it. Deacon noted in his diary, "everybody drunk tonight." Deacon went to see all of his girlfriends before going over to Glenferrie to visit Shirley and her family. Sid didn't go. He had said his good-byes weeks earlier.

At inspection the next morning, Lieutenant Benson and the top sergeant were both caught drunk. A lot of yelling ensued. A number of summary courts-martial were issued. By evening they had sorted it out and boarded the ship. A large crowd had gathered, a "waving, crying, flag- waving mob" on the dock. The local police and the Australian army's military police (MPs) were called out to keep them back. On deck, the marines blew air into their remaining prophylactics and let them drift to shore. Sid thought inflated condoms might just be going too far. The ship cast off and stood out from Melbourne's great harbor that same evening. For the next week, it steamed along the Great Barrier Reef, host to a battalion of marines cursing Liberty Ships, C rations, and "Dugout Doug." The men of the 2/1 figured they were headed for Rabaul or Bougainville. Rabaul was six hundred miles from Guadalcanal; Bougainville was even less. By implication, not very much progress had been made in the ten months since the #4 gun squad had last steamed through the Pacific. Looking forward to another six months stuck in a jungle, a crowd of marines took over Deacon's bunk and played for stakes as high as PS100.

THE NAVY INCENTIVE TOUR HAD TURNED OUT TO BE QUIET AND BORING, WITH the occasional interview. The reporters may have worn Manila down because his resolution faded. In New York on October 15, the reporter Julia McCarthy tried to peel away some of the myths. She asked, "Didn't you personally kill thirty-eight Japanese, or have we been told wrong?" Before he could answer, she followed it with another: Had Manila really moved his machine gun because he had piled up so many dead? John nodded; all that was true. What about the rumor, McCarthy continued, that he had been offered a commission? John "at first admitted, then denied a report he turned down a chance to become a second lieutenant."

148

His denial may have come from a desire to protect himself from being criticized for declining the opportunity for advancement. "The title I like best is 'Sarge,'" he explained, "and I like to be in the ranks.' "

149

The incentive tour proved to have lots of holes in it, so John frequently returned to D.C. He began dating one of the female marines working in the Navy Building. When the final tour event ended on October 19, he was given a month's furlough, so he moved back to the three-bedroom duplex in Raritan where his parents had raised ten children.

150

Most of his older brothers and sisters had long since moved out, though. Manila and his younger brother Don, who was just a boy, shared a room. Two sisters lived in the other.

151

All of the news stories had been published by mid-October. His mother had a large scrapbook, although it's unlikely John ever read it. The long interviews had not changed the coverage very much. The Basilone household received a lot of fan mail in October. The early articles in the summer had gotten a few people to write John and his family. The photographic essay in

Life

and the national radio broadcasts, however, generated lots of mail. Mothers wrote to congratulate his parents. The parents of men in his outfit wrote to congratulate him. They sent clippings; they wanted to know if Basilone had seen their boys in the South Pacific. Kids wrote for autographs. Old girlfriends wanted to catch up. Women he had met on the bond tour wanted to know how it all went. A dozen women sent pictures to John and introduced themselves to him. More than a few struggled with how to start a letter to a hero they did not know. Each acknowledged that he was being besieged by letters, but as one wrote, "I'm keeping my fingers crossed a little and hope you'll answer this letter, crummy and dull as it is."

152

John enjoyed reading the letters, which his mother saved for him. Some friends from his hitch in the army wrote to congratulate him. They were proud to have soldiered with him. Of course, being old buddies, they had to tease him, too. " The only part that bothers me is that you had to be in the marines," said one.

153

Everyone--old friends, friends of friends, former neighbors, former teachers, strange women, fans--all of them begged him to write them back, to call them, to let them know he had heard from them. They acknowledged how busy he was, but pleaded for a visit. They also called his house, called his brothers, and left word with his cousins.

Among the mail came a slick brochure from the War Activities Committee of the Motion Picture Industry, wrapping up the success of its Third War Loan Campaign. Flight Five of the Airmada, featuring Manila John, John Garfield, Virginia Grey, and others, had sold just over $36 million in war bonds. A few others had a higher total. Flight Three had topped them all with $94 million in bond sales.

154

In late October, John went up to visit his friend Stephen Helstowski in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

155

The real reason, as Steve knew, was for John to meet Steve's sister Helen. He had been infatuated with her since he received her letters on Guadalcanal. Since his return to the States, Basilone had spoken of her several times to the press with such enthusiasm, it was reported that he would marry Helen Helstowski.

156

He spent a few days there, double-dating with Steve and his girlfriend. They got along very well and the relationship grew serious.

157

He could not stay long, though. In early November he boarded a train for Raritan.

158

There was more work to be done.

EUGENE SLEDGE'S HOLIDAY BREAK FROM THE V- 12 PROGRAM DID NOT GO AS HE expected. He returned to Georgia Tech three days early. Whatever the reason he gave his family, the tension inside of him resulted from the secret he was keeping from them. He had flunked both physics and biology and earned Cs in English and economics. So far as Captain Payzant could tell, Private Sledge was "below average" in intelligence and "not inclined to study," nor did he possess the "necessary officer qualities." The dean of the college agreed with Payzant's recommendation that Sledge be reassigned. On October 31, 1943, Private Sledge and forty-four of his colleagues were put under the command of Corporal James Holt, who escorted them to the Marine Corps base in San Diego "for recruit training and general service."

The recruits shipped out the very next day. Their train to San Diego stopped in Mobile for a few hours before steaming across the Southwest. Eugene did not attempt to phone his parents. He feared their reaction. He waited to write to them until the end of his first complete day of boot camp at the USMC Recruit Depot, which was also his twentieth birthday. The letter explained that he had not flunked out. Upon reviewing his file, Captain Payzant had decided that Sledge was not prepared for the engineering course required in the second semester, since he had had no previous courses it in. "At the last minute," Sledge had been "reassigned." Although Gene had asked to remain in the program, the captain had sent him to boot camp. "So you see," Eugene concluded his first letter to his parents, "I don't feel bad about coming here." He described his delightful train trip across the country. The mountains of Arizona had been especially beautiful, leading him to suggest a family trip to visit them after the war.

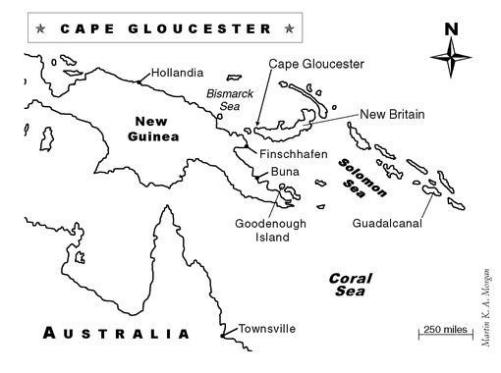

THE BATTALIONS OF THE 1ST MARINE DIVISION WERE DISPERSED AFTER THEIR troop transports had steamed back within range of "subs and jap heavy bombers" in mid-October. Some units found themselves on the eastern tip of New Guinea. Sid's 2/1 built their bivouac on Goodenough Island, one of a small group of islands near the tip of New Guinea and firmly under the command of MacArthur. One look at Goodenough Island and most concluded the 1st Division was "back in the boonies again!"

159

Sidney saw a "beautiful island with mountains which seemed to touch the sky." They set up their bivouac near the base of a mountain, pausing every few minutes because of the enervating heat. A clear, cold mountain stream beckoned them in the afternoon. Being near an airstrip and a river made it all seem familiar, although this time there were no enemy forces on the island--just "gooks," the marines' popular slang word for any nonwhites.