The Palace of Laughter (28 page)

Read The Palace of Laughter Online

Authors: Jon Berkeley

HG:

Have you remained with the circus ever since that first performance?

SM:

Who else would have me? I always had itchy feet, so I put many miles behind me over the years, and I worked with some of the greatest circuses in the world.

I was with Antonio Franconi in France, but I fell out with him over a steak and kidney pie and had to leave the country, so I stowed away on a ship for Montreal, and there I joined the Circus of Pepin and Breschard. We toured from Montreal to Havana, building circus theatres everywhere we went.

HG:

Why did they build theatres? Didn't they have circus tents in those days?

SM:

Not until I came up with the idea. I joined the circus of Joshua Purdy Brown, and I nailed my thumb to many a plank building theatres for his show. My lodgings were a small tent far from the sensitive nostrils of the ringmaster, and I dreamed one night that the tent grew and grew until it could swallow five hundred people. I woke Mr. Purdy Brown at the crack of dawn and said “What you need is a monstrous tent!” That was in 1825, and they've been popular ever since, though Joshua Purdy Brown got all the credit for the idea.

HG:

How did you get the name “the Shrunken Man of Kathmandu”?

SM:

The famous P. T. Barnum gave me that title. He was the first to add a freakshow to his circus, and that innovation suited me fine. I could sit in my comfortable wagon and folks would pay half a dollar to see me by candlelight. It beat being trodden on by horses and sneezed on by camels, I can tell you. Eventually Barnum's circus merged with James Anthony Bailey's, and toured Europe as The Greatest Show on Earth. That was how I came to be back here, and I've been with one show or another ever since. Still got the itchy feet, you know.

The Shrunken Man stretched himself in the gloom, extending a hairy foot with thick yellow nails into the small strip of light that sliced in through the half-closed door.

SM:

Speaking of which, maybe you could give the old foot a scratch there. I'm not as young as I used to be, and it's a struggle to reach me own toes these days.

HG:

Actually, I can hear someone calling me. My wife is ill at home. I left a pot on the stove. Thank you for your time, Mr. Kathmandu. I'll see myself out.

Â

Â

PUZZLE PAGE

MILES'S BRAIN TEASER:

Q:

If it takes a farmer a year and a half to raise 24 sheep on 4 acres, and a wolf can run at 20 miles per hour for 8 minutes on an empty stomach, how much does the farmer need to spend on fencing wire?

Â

A:

Nothing. He can sell the sheep and use the money to put in a vineyard. Wolves don't eat grapes.

CAN YOU PUT THE NULL BACK IN HIS WAGON?

LADY PARTRIDGE'S JOKE OF THE WEEK:

Q:

How many letters in TIGER?

Â

A:

Depends how many mail carriers he ate, my dear.

CHESS MASTER CLASS

with THE BOLSILLO BROTHERS:

WHITE: 1. Knight to c3.

BLACK: Pawn to d5.

Â

WHITE: 2. Up to answer door.

BLACK: Bishop to f5.

Â

WHITE: 3. Whose turn is it?

BLACK: Kettle to hob2.

Â

WHITE: 4. Three aces.

BLACK: You can't have three aces!

Â

WHITE: 5. They used to be bishops.

BLACK: King to lose head.

Â

WHITE: 6. A hotel on Boardwalk.

BLACK: Check mate.

Â

WHITE: 7. Check your own mate. I have a full house.

BLACK: In that case I surrender.

THE WEDNESDAY TALES ~ NO. 2

THE TIGER'S EGG

A LOOSE CANNON

A

long a hospital corridor marched a man on squeaking shoes, dressed in an outsized orderly's uniform. He had a small round head and pale gray eyes, and he called himself the Great Cortado. Stuck to his upper lip, where his magnificent mustache had been only minutes before, was a tiny square of tissue paper with a spot of blood at the center. He was walking quickly toward the hospital entrance, away from the room where he had spent the past three months under lock and key. The room was locked again now,

and the key was in his pocket. The uniform he wore belonged to the real hospital orderly, who lay unconscious on the floor of the locked room, his wrists and ankles tied with strips of torn bedsheet. The orderly had been hit over the head with a heavy steel tray, and would not be waking up anytime soon.

The Great Cortado squeaked through the reception area, past the desk where the night doorman sat reading his paper. The doorman looked up and frowned. “Knocking off early?” he said, glancing at his watch. “Shift doesn't end till four.”

“I'm going on strike,” said Cortado, “for better conditions.”

The doorman put down his paper and raised an eyebrow. “Strike?” he said. “Is it official?”

“Whatever,” said the Great Cortado, and he pushed the revolving door and spun himself out into the frosty night air.

His foggy breath was lit by the lamps that lined the gravel driveway, and the cold bit his upper lip. A snigger escaped him, and he clamped his mouth shut. Better nip that in the bud. Once he started it could get the better of him. He marched out through the gates and along the tree-lined street beyond, his

head filled with a tumult of sounds and pictures, of cackling and howling and falling and spinning. Night and day this freak show went on inside his mind, and he walked a tightrope through the chaos, sometimes slipping off and losing himself for days. Now was not the time, he told himself, and he fixed his eyes on a spot ten feet ahead of him as he walked. One step at a time. Left, right, left, right, up, down and sideways. No skipping. Another laugh bubbled up and he forced it back down. “Concentrate,” he muttered. “You are the Great Cortado.”

“You

were

the Great Cortado,” said a voice at the back of his head. He spun around, but there was no one there. “Nobody here but us chickens,” he said. “I

am

the Great Cortado. Just a minor setback. Once I get back on my feet, then we'll see who's laughing.”

He marched on unsteadily into the night, the once Great Cortado, sudden giggles exploding from him like hiccups. As the cold air washed the hospital drugs from his system his old plans and schemes began to rise up through the madness, stranger than they had been before, darker and more crooked. An army of slaves. A city of bones. A military-industrial complex bristling with rockets and roaring with ire. He

breathed deeply and allowed himself to laugh aloud. No matter what monstrosity he chose to build or how he trampled his way to power, there was one thing he knew for sure. At the gates of his empire there would be a tall straight pole, and on that pole would be the head of Selim, the boy who had brought down the Palace of Laughter. “Item one on my shopping list,” said the Great Cortado to the empty streets, “Selim's head on a pole. Then we'll see who's laughing!”

Â

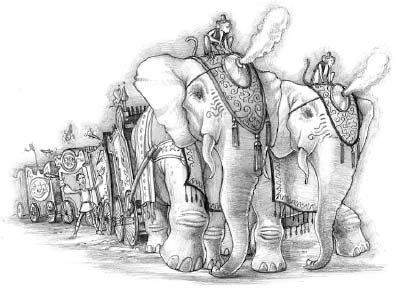

The Circus Bolsillo came to Larde on a crisp February morning. From the moment the first wagons appeared over the brow of the hill it was clear that this was a circus without equal. A pair of elephants led the parade, painted and tasseled and each with a waistcoated monkey perched between her ears. They were followed by a gap-toothed man with slicked hair, juggling a dozen flaming clubs. A troupe of tumblers cartwheeled along the frosty road, their breaths tracing spirals of vapor that vanished at once in the winter sun, and behind them came a procession of wagons and trucks, painted in bright colors and each one more exotic than the last. They rode in on a wave of drums, whistles and gongs that could

wake the dead, and the strange hoots and rumbles of animals from far-off jungles and distant deserts. The lead wagon was painted with the words

THE INCOMPARABLE CIRCUS BOLSILLO

in reds, blues and yellows, and in the large round Os were painted the grinning faces of three little clowns with pointed teeth.

A small girl and a coffee-skinned boy sat on the parapet of the stone bridge that led into Larde, oblivious to the cold and waiting eagerly for the circus to reach them. The boy's name was Miles, and the girl was known as Little. Sitting side by side on the cold stone they might seem unremarkable enough, if you did not know that Little was over four hundred years old and had the outline of a pair of lost wings etched into the skin of her back, or that Miles had befriended a talking tiger and carried in his pocket a small stuffed bear that could dance like a drunken sailor.

The lead wagon drew closer, and Miles and Little could see the Bolsillo brothers themselves, Fabio, Umor and Gila, balanced on the roof like a small totem pole. As they rumbled across the bridge the totem pole made a triple bow. “How are you, Master Miles?” shouted Fabio over the racket of the circus band. “And the little lady, Lady Little?” called Umor,

and Gila showed his pointy teeth in a broad smile.

“Fine, I suppose,” shouted Miles. “How's the new circus shaping up?”

“Can't complain,” called Fabio.

“Yes we can,” shouted Gila.

“But we won't,” said Umor, his voice almost lost in the cacophony.

Miles and Little fell into step with the Bolsillo brothers' wagon, which was drawn by two enormous cart horses with legs like fringed pillars, but were soon caught up in the dense crowd that had spilled onto the streets, and stopped where they were to watch the rest of the parade go by.

The Circus Bolsillo could not have been more different from its predecessor, the Circus Oscuro, which had crept into town in the dead of night not six months before. That sinister outfit was disbanded now, and its ringmaster had been locked away in a secure hospital, but from its remains the Bolsillo brothers had built a brand-new circus, as colorful and chaotic as the Circus Oscuro had been eerie and dark. They had brought in new performers to replace those who were missing or jailed, and as their fabulous procession rolled by, Miles could see

just what a remarkable show they had created.

There were many more wagons, brightly painted with the names of exotic acts and sideshows: the Toki sisters from the Far Orient, Countess Fontainbleau and her Savage Lions, K2 the Strongman, Doctor Tau-Tau Presents Your Future. Something about the name on that last wagon sounded familiar to Miles, but he was distracted by a cage fat with crocodiles that rolled by in its wake. The sleepy reptiles were draped across each other like saggy statues, their crooked grins hinting that they might just be quietly digesting a small child or two. Miles was secretly hoping to catch a glimpse of a tiger somewhere in the colorful parade. There were animals from every corner of the world, but he was not really surprised when the last wagon passed and the only stripes he had seen were on whinnying zebras and folded canvas.

Miles and Little followed the tail of the Circus Bolsillo, even as the first wagons were pulling into the long field at the bottom of the hill. Lady Partridge, who ran the orphanage that they called home, had told them that the circus was coming, although she could not say when, and that they

would be quartering their animals in the old stables behind Partridge Manor for a few days before taking to the road for the spring season.

By the time Miles and Little arrived at the long field, the wagons and trucks had arranged themselves in a broad circle around its edge, and those first to arrive had already spilled from their traveling homes with their dogs and children and washing lines and folding chairs and basins and chickens and oil lanterns. Canvas canopies cracked in the wind as their corners were lashed to nearby trees. A generator on a small yellow truck roared into life, and Fabio Bolsillo appeared from behind it, wiping his hands on an oily rag. At the sight of Miles and Little his face broke into a grin, and he shoved the rag into the back pocket of his overalls and turned a quick cartwheel that brought him right up beside them. He bowed low, and gave Miles a sly wink.

“Thought you'd come sniffing around,” he said.

“Like flies around horse dung,” said Gila, who had appeared from nowhere.

“Where's Umor?” asked Little.

“Cooking,” said Gila.

“We're expecting guests,” said Fabio.

“Oh,” said Miles. “Then we'll go. We just came to say hello.”

“Go if you want,” shrugged Gila.

“Then we'll have no guests,” said Fabio.

“All the more for us.” Gila reached out, quick as a flash, and tweaked Miles's nose.

“Ommadawn,”

he said.

As they walked toward the Bolsillo brothers' wagon, Fabio gave Miles a sidelong glance from under his bushy eyebrows. “I suppose you've heard the news from Flukehill?” he said.

A cold feeling stole over Miles. “What news?” he asked.

“The Great Cortado escaped from the secure hospital last week,” said Fabio.

“Hit his warder over the head with a steel tray,” said Gila.

“Shaved off his mustache with a sharpened butter knife.”

“Dressed himself in the warder's clothes and marched straight out of the door.”

“Told the guard he was going on strike.”

Miles felt his stomach tighten, and for a moment the ground seemed to tilt away beneath his feet. He

could see Little looking at him anxiously from the corner of his eye, and he made himself smile at her. “I don't think he'll get far before they catch him again,” he said. He pictured Sergeant Bramley and his two trusty constables, filling in the crossword over mugs of steaming tea, and quickly pushed the thought from his mind.

“I wouldn't be so sure,” said Fabio.

“He's a master of disguise,” said Gila.

“And handy with a knife!” said Fabio.

“He's been sighted in Nape, and Iota, and as far away as Frappe,” said Gila.

Fabio pulled Gila's cap down over his eyes. “Rumors and lies,” he snorted, “unless he's sprouted a propeller since we saw him last.”

Miles laughed, and the knots in his stomach eased slightly, but still he felt that a cloud had stolen over the day, and he reached into his pocket for the reassuring feel of his orange-gray stuffed bear, Tangerine, who had been sung to life by Little on a moonlit autumn night. Tangerine said nothing, but he gave Miles's fingers a squeeze that said more than a pocketful of words.