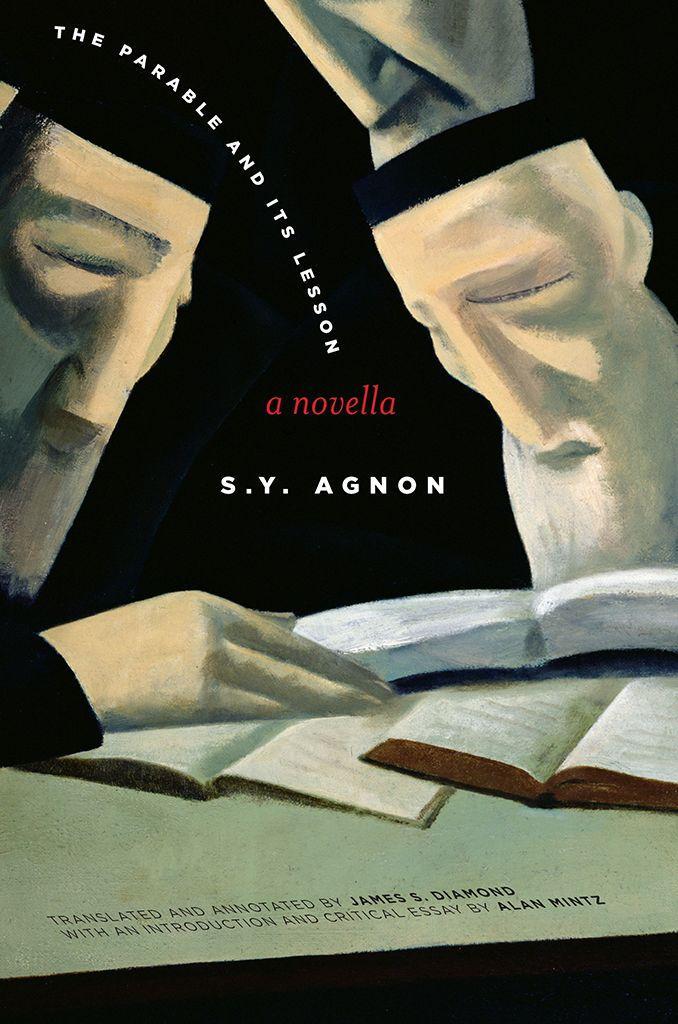

The Parable and Its Lesson: A Novella

Read The Parable and Its Lesson: A Novella Online

Authors: S. Y. Agnon

Tags: #Movements & Periods, #World Literature, #Jewish, #History & Criticism, #Literature & Fiction, #Criticism & Theory, #Regional & Cultural

The Parable and Its Lesson: A Novella

S. Agnon & Alan Mintz & James Diamond

Stanford University Press (2014)

Rating: ★★★★★

Tags: Literature & Fiction, History & Criticism, Movements & Periods, Regional & Cultural, Jewish, Criticism & Theory, World Literature

Literature & Fictionttt History & Criticismttt Movements & Periodsttt Regional & Culturalttt Jewishttt Criticism & Theoryttt World Literaturettt

S.Y. Agnon was the greatest Hebrew writer of the twentieth century, and the only Hebrew writer to receive the Nobel Prize for literature. He devoted the last years of his life to writing a massive cycle of stories about Buczacz, the Galician town (now in Ukraine) in which he grew up. Yet when these stories were collected and published three years after Agnon's death, few took notice. Years passed before the brilliance and audacity of Agnon's late project could be appreciated.

The Parable and Its Lesson

is one of the major stories from this work. Set shortly after the massacres of hundreds of Jewish communities in the Ukraine in 1648, it tells the tale of a journey into the Netherworld taken by a rabbi and his young assistant. What the rabbi finds in his infernal journey is a series of troubling theological contradictions that bear on divine justice. Agnon's story gives us a fascinating window onto a community in the throes of mourning its losses and reconstituting its spiritual, communal, and economic life in the aftermath of catastrophe. There is no question that Agnon wrote of the 1648 massacres out of an awareness of the singular catastrophic massacre of his own time—the Holocaust.

James S. Diamond has provides an extensive set of notes to make it possible for today's reader to grasp the rich cultural world of the text. The introduction and interpretive essay by Alan Mintz illuminate Agnon's grand project for recreating the life of Polish Jewry, and steer the reader through the knots and twists of the plot.

Review

"Agnon is perhaps the greatest brooding presence in Israel's angst-filled literary stable, and richly deserves first-rate translation. The pairing of Mintz and Diamond is splendid, and they've managed to open up Agnon to a new generation of readers."—Steven Zipperstein, Daniel E. Koshland Professor in Jewish Culture and History, Stanford University

"The time has finally come to introduce readers, scholars, and students to the work of 'late Agnon,' which is both unfamiliar and misunderstood. One could not hope for a better introduction than this volume. It will make one of Agnon's unknown masterpieces accessible to readers, and will expand our knowledge and understanding both of Agnon's writing and of literary responses to the Holocaust."—Shachar Pinsker, Associate Professor of Hebrew Literature and Culture, University of Michigan

About the Author

S. Y. Agnon was born in 1888 in Buczacz, Galicia. He emigrated to Palestine in 1908 and lived there for five years before beginning an extended stay in Germany. He returned to Palestine in 1924 and settled permanently in Jerusalem. He received the Nobel Prize in literature in 1966. James S. Diamond is a rabbi, academic, and translator. He taught literature at Princeton University for over a decade, and has written extensively on Agnon and modern Hebrew literature. Alan Mintz is the Chana Kekst Professor of Hebrew Literature at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York. He is author, most recently, of

Sanctuary in the Wilderness: A Critical Introduction to American Hebrew Poetry

(Stanford, 2011). He was a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in 2012.

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

Introduction, Essay, and English Translation of

The Parable and Its Lesson

©2014 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

The Parable and Its Lesson

was originally published in Hebrew in 1973 under the title

Hamashal vehanimshal

, having appeared as one of several stories in the volume

‘Ir umelo’ah

© 1973, Schocken. The English translation is printed with permission.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Agnon, Shmuel Yosef, 1888-1970, author.

[Mashal veha-nimshal. English]

The parable and its lesson : a novella / S.Y. Agnon ; translated and annotated by James S. Diamond ; with an introduction and critical essay by Alan Mintz.

pages cm—(Stanford studies in Jewish history and culture)

“Originally published in Hebrew in 1973 under the title Hamashal vehanimshal, having appeared as one of several stories in the volume ‘Ir umelo’ah.”

ISBN 978-0-8047-8871-1 (cloth : alk. paper)—

ISBN 978-0-8047-8872-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Jews—Ukraine—Buchach—Fiction. I. Diamond, James S., translator. II. Mintz, Alan L., writer of introduction, writer of added commentary. III. Title. IV. Series: Stanford studies in Jewish history and culture.

PJ5053.A4M3513 2014

892.43'5—dc23 2013039418

ISBN 978-0-8047-8925-7 (electronic)

Designed by Bruce Lundquist

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 11/15 Adobe Garamond

THE PARABLE AND ITS LESSON

a novella

S.Y. AGNON

TRANSLATED AND ANNOTATED BY

JAMES S. DIAMOND

WITH AN INTRODUCTION AND CRITICAL ESSAY BY

ALAN MINTZ

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD, CALIFORNIA

STANFORD STUDIES IN JEWISH HISTORY AND CULTURE

EDITED BY Aron Rodrigue and Steven J. Zipperstein

James S. Diamond (1939–2013)

IN MEMORIAM

CONTENTS

Alan Mintz

S. Y. AGNON

Translated and Annotated by James S. Diamond

Essay on

The Parable and Its Lesson

[

Hamashal vehanimshal

]

Alan Mintz

Printed with permission of Beit Agnon

.

INTRODUCTION

ALAN MINTZ

The decisions of the Nobel committee on literature have often been curious, but the award of the prize for 1966 to S. Y. Agnon (together with Nelly Sachs) was not one of those instances. At the time, Agnon was generally regarded as the greatest modern Hebrew writer, and the prize richly deserved. It was also an important moment for Israel and its citizens because this was the first time—and so far the only time—a Hebrew writer was given the award, and the honor was taken as a recognition of the achievements of this new literature in general. Agnon lived just long enough to take great pleasure in the honor and to enjoy the tributes given him not only in Israel but in the United States, which he visited for the first time the year after the award. Agnon died in 1970 at the age of eighty-two.

Agnon’s output was prodigious. He wrote and published continuously from 1905 to his death, after which fourteen more volumes appeared, to be placed alongside the several versions of the collected stories and novels that came out in his lifetime. Agnon was a ceaseless rewriter, and there is scarcely a major text in his oeuvre that has not undergone several revisions. Although Agnon’s forte was the story in all its short and long forms, he also wrote five major novels and devoted himself to compiling thematic anthologies of Jewish classical sources. Rather than turning from one form and immersing himself in another, Agnon would typically work on several projects in different genres at one time. Because the ongoing body of his work is dynamic, polyphonic and unstable, it has been difficult for critics to divide Agnon’s career into usefully identifiable phases. Yet despite these challenges, most students of Agnon would point to the twenty years following his return to Palestine from Germany in 1924 as the high water mark in the master’s career. All of his novels were published or written during this time, as were the modernist parables collected in

The Book of Deeds

[Sefer Hama’asim]. These latter were the stories that changed the way contemporary readers perceived Agnon. Initially viewing him as a teller of naïve tales of Polish Jewry, readers subsequently came to accept him as an ironic modern master.

From the end of World War Two to his death, Agnon continued to write, revise and publish prolifically, but the work produced during this period seemed to most critics to be a continuation of the various modes, genres and themes of his earlier writing. It is generally assumed that this creative activity was aimed at tying up loose ends, bringing projects to fruition and extending the range of previously secured innovations.

It is now clear that this conception of Agnon’s last phase needs to undergo a fundamental revision. We can now see that one of Agnon’s postwar projects was entirely new: a preoccupying, ambitious, large-scale undertaking that represented a fundamental rethinking of the master’s relationship to the world of Eastern Europe. This is the epic cycle of stories—close to 150 of them—written during the 1950s and 1960s about Buczacz, the Galician town, today in the eastern Ukraine, in which Agnon grew up and lived until his emigration to Palestine at the age of nineteen in 1907. None of the material appears in any earlier collection. The whole was compiled by the Agnon’s daughter Emumah Yaron, according to her father’s instructions, and published under the title

‘Ir umelo’ah

[

A City in Its Fullness

] in 1973. The story cycle endeavors to give an account of Buczacz during the two hundred years that followed the devastating Khmelnitski massacres of 1648. Taken together, the stories constitute Agnon’s comprehensive effort, after the annihilation of European Jewry, to think through the question of what from that lost culture should be retrieved through the resources of the literary imagination.

‘Ir umelo’ah

was hardly noticed when it was published, and it remains largely unknown to the non-Hebrew reading world. Yet I would argue that it is one of the most extraordinary responses to the murder of European Jewry in modern Jewish writing.

Hamashal vehanimshal

, the novella from that collection presented and translated here as

The Parable and Its Lesson

, reaches back in time to explore the responses to the 1648 massacres in light of our implicit awareness of the great catastrophe of our era. It is a good representative of the larger project of the Buczacz tales because it is concerned both with capturing the pathos of a historical moment in the fortunes of the city and with the ways in which narrative and voice refract reality. Agnon’s passion remained the disingenuous act of storytelling.

The Parable and Its Lesson

, with its two narrators and sustained monologue and intriguing fissures, provides an excellent instance of Agnon’s mature narrative energies at full tilt.

What is Agnon for us today? Does he number among those once-famous writers who now seem to belong to another time and another world of taste? To be sure, his portrait and quotations from his Nobel Prize speech appear on the fifty-shekel note in Israel, but that only guarantees him a place alongside other forgotten founders. Or does Agnon’s work qualify as being a true classic, if we understand a classic as literature that, despite its rootedness in a particular time and place and conventions of writing, nonetheless possesses enough surplus of meaning to speak to us now? For the present, Agnon’s place among cultured readers in Israel is secure, although the increasing polarization between secular and religious culture may eventually endanger that status; for the former he may come to seem too foreign and the for latter impure simply for being literature. For young people, Agnon is one of those standard authors you have to get through for exams, even though sensitive readers will often rediscover him as adults. Reading Agnon is not easy. Even committed and discriminating readers who are native speakers of Hebrew have to deal with many unfamiliar references, especially if they lack a background in traditional Jewish texts. The fact that Agnon continues to be read despite these obstacles provides evidence for the claim that he is indeed a classic.