The Pentagon: A History (11 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

Before leaving town, Roosevelt had taken care of a pressing matter. After huddling with Harold Smith at noon on Friday, Roosevelt signed a letter to Senator Alva Adams, chairman of the Senate Appropriations subcommittee that was to consider the new War Department building. The letter offered a revisionist account of the green light the president had given Stimson at the cabinet meeting a week earlier. “When this project was first brought to my attention, I agreed that it should be explored,” Roosevelt’s letter read. “Since then I have had an opportunity to look into the matter personally and have some reservations which I would like to impart to your committee.”

Those reservations were directed solely at the building’s size and not its location, Roosevelt added. “While I am in full accord with this general objective of providing additional permanent space and have no objection to the use of the Arlington Farm site for an office building for the War Department, I do question the advisability of constructing the entire 4,000,000 sq. ft. on the proposed site without first being reasonably sure that the present and proposed traffic and transportation facilities can accommodate” all the expected workers, he said.

The letter, drafted by Smith and using language very similar to that sent by Delano to the Senate the day before, urged the Senate to approve “a smaller building” limited to twenty thousand employees. More space could be added later if needed, Roosevelt said.

With all final business attended to, Roosevelt appeared not to have a care in the world as he headed out of town. The presidential train pulled out of Union Station at 11

A.M.

on August 3, headed for New London, Connecticut, where Roosevelt’s yacht, the USS

Potomac,

was waiting. The president looked relaxed and cheerful, boasting of the number of fish he expected to catch. “It was no more than the start of a vacation for a man who has…longed for some sea air,”

The New York Times

reported.

It was a good deal more than that.

Potomac

was scheduled for a surreptitious night rendezvous off Martha’s Vineyard with the heavy cruiser USS

Augusta,

flagship of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet.

Augusta,

in turn, escorted by another heavy cruiser and five destroyers, would carry Roosevelt to waters off Newfoundland for a secret meeting—his first as president—with Winston Churchill, prime minister of Great Britain.

Almost everyone back in Washington, even senior government officials, was in the dark about the president’s mission. Congress remained in session, and in the president’s absence the debate over the new War Department building erupted into a full-fledged controversy.

Somervell confidently moved forward to construct the building on his own terms, making no adjustments to shrink it. The Office of Production Management, the government agency overseeing war-mobilization efforts, approved his contract with McShain on August 4. The following day Somervell ordered test borings of the Arlington site.

Yet there was no denying Somervell had suffered quite a reversal. In the first two weeks since launching the project July 17, he had rolled to one victory after another. But as July turned to August, the stiffening resistance from the fine arts and planning commissions had begun to turn the tide. Harold Smith—whom Henry Stimson considered to be “the most dangerous opponent” of the building—was fighting an effective battle behind the scenes at the White House. Skepticism was growing in Congress. Now, worst of all, Roosevelt wanted the building’s size cut in half.

A hearing was set before Senator Adams’s appropriations subcommittee on August 8. Somervell’s burgeoning league of opponents was taking aim not only at the building’s size, but also its location. Harold Ickes, Roosevelt’s own interior secretary, complained the president’s proposal to halve the size of the building was no solution. “In other words, Lee House and the Washington Monument would look down upon only 17

1

/2 acres of roofs instead of about 35 acres,” the interior secretary noted sardonically in his diary. Contradicting the absent president’s views, Ickes telephoned Adams and strenuously objected to the building’s location.

Clarke, the fine arts commissioner, also lobbied senators, sending an impassioned letter August 2 to the Appropriations Committee and distributing copies to reporters. “Are we going to create a blot upon the landscape which can never be erased and which will be regretted for decades after this emergency is past history in the minds of future Americans?” Clarke asked.

As an afterthought, Clarke sent a copy to Somervell. The general’s one-sentence reply to Clarke on August 5 was curt, but it spoke volumes of disdain: “I acknowledge receipt of your letter of August 2 to the Committee on Appropriations of the United States Senate, previously published in the newspapers.”

The newspapers had indeed picked up the cry. The

Star

photographed the proposed site from the Goodyear blimp, floating high above the Lee mansion. The picture was run across five columns with an accompanying declaration by the paper that “the unparalleled view of Washington from the heights of Arlington Cemetery would be distorted by acres upon acres of ugly flat roofs.” A

Star

editorial declared such a building “certainly would be an act of vandalism,” and the newspaper blamed Somervell. “In the course of a few hours, an Army officer with no experience in city planning and without consulting any planning agency, ‘sold’ a House Appropriations Committee on a new scheme—to…build a stupendous War Department Building.” Out-of-town papers weighed in with their own criticism. “Defense is a necessity, but it is not necessary that structures erected for any of its purposes should be an offense against esthetics,”

The New York Times

lectured.

The National Association of Building Owners and Managers contended such an enormous building would hurt the rental market and be an “economic liability” after the war. Prominent senators criticized the notion of the War Department abandoning Washington. “Once you do this, we may have all our federal departments scattered all over the United States,” warned Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr., of Massachusetts. “This city may be a ghost town after the emergency,” echoed Robert R. Reynolds, chairman of the powerful Military Affairs Committee.

Reynolds, with support from other senators, proposed that the building instead be constructed on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, a venerable retirement facility for veterans established in 1851 with booty brought home from the Mexican War on a large, leafy oasis in the northern reaches of the city. Rolling fields around the home held what a newspaper described as “one of the world’s finest herds of Holstein Friesian cows; plus an equally distinguished flock of White Leghorn chickens” that helped provide food and sustenance to the veterans. All of them—old soldiers, chickens, and cows—should be evicted, lock, stock, and barrel, in the view of the

Star,

which heartily endorsed Reynolds’s proposal.

Lodge, on the other hand, favored razing poor, primarily black neighborhoods in Washington to keep the War Department in the city, thus killing two birds with one stone, in his opinion. Citizens came forward with their own suggested locations, among them amid the trees of the National Arboretum in Northeast Washington or surrounded by juvenile delinquents on the nearby 350-acre grounds of the National Training School for Boys, a reform school.

Barely noticed in all the uproar was an informal suggestion from Jay Downer, a consultant for the Public Roads Administration, who had often worked with Gilmore Clarke on parkway projects in New York. He was now planning roads to tie northern Virginia together with the District of Columbia, and was intimately familiar with the land in the area.

On the morning of August 6, Downer telephoned Hans Paul Caemmerer, the longtime secretary of the Commission of Fine Arts and a passionate L’Enfant disciple who served as Clarke’s eyes and ears in Washington. The War Department owned another vacant plot of land in Arlington, Downer told him, this one immediately south of the Arlington experimental farm and adjacent to Washington-Hoover Airport. The War Department had just broken ground for a quartermaster depot on the site. Why not use this land for a temporary headquarters, Downer suggested.

Caemmerer quickly contacted Clarke in New York. The chairman liked the idea. There would be no aesthetic concerns about building on this low-lying, ignoble tract of land. A telegram was sent the same day to Delano, in Salt Lake City on business, asking his reaction. Delano telegrammed back his approval the next day, calling it “much more agreeable” than Somervell’s proposal.

A consensus was settling in many quarters around town that the new War Department simply could not be built at the foot of Arlington Cemetery, a location where it would desecrate the view from the tomb of Pierre L’Enfant. Surely these were plans that the War Department “will gladly give up in the light of fuller information,”

The New York Times

told its readers. In this the

Times

was quite mistaken; like many others, it had failed to reckon with General Somervell.

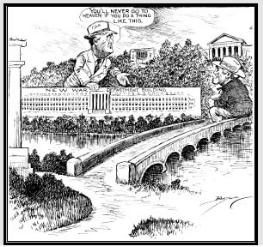

Clifford Berryman cartoon from the Washington

Evening Star,

Aug 20, 1941.

A hell of a mess with Congress

Brigadier General Brehon Somervell, brimming with righteous purpose and armed with maps and figures, strode into the Senate Appropriation Committee’s meeting room on the first floor of the Capitol on the morning of August 8, 1941, ready for the showdown over the War Department building in Arlington. Newspaper reporters lurked in the hallway outside as senators and witnesses arrived. The hearing was closed to the public, and frustrated reporters tried to get a fix on the fate of Somervell’s building.

“What do you think of this proposal?” a reporter called to Senator Carter Glass of Virginia, the imperious, white-haired chairman of the Senate Appropriations Committee, who everyone in the Capitol knew would have enormous influence determining the outcome. “I’m going to tell the committee how I feel, not the newspapers,” Glass snapped.

Inside the committee room, Gilmore Clarke, chairman of the Fine Arts Commission, wasted no time denouncing Somervell’s proposed building. “We think it would be one of the most serious and worst attacks on the plan of Washington that has ever been made,” he testified.

Senator Alva Adams, the subcommittee chairman, tried to broker a compromise, asking about Roosevelt’s declaration that the building’s size should be cut in half. “That reduction in capacity doesn’t meet your criticism at all?” the senator asked.

“No, sir; that wouldn’t meet our sanction at all,” Clarke replied. “We are opposed to any building whatever on that Arlington site.”

The strident opposition rubbed senators the wrong way. Clarke “was too sarcastic and unbending,” Harold Ickes noted in his diary. “Then General Somervell, whose pet this scheme seemed to be, had his turn and he swept all before him.”

Somervell summarily rejected the sites proposed by his opponents. No other site but Arlington Farm would do for the War Department, the general insisted. Foggy Bottom, the Washington neighborhood where the New War Department Building was located, could not possibly accommodate a building of this scale; the area was congested and parking nonexistent.

Somervell reserved his greatest scorn for the quartermaster depot site, set in a picaresque neighborhood known as Hell’s Bottom. “The Chairman of the Fine Arts Commission thinks it is all right to put the War Department down among a lot of shanties, brickyards, dumps, factories and things of that kind, but I think the War Department is worthy of a little better place,” he said.

Arlington Farm should be put to a more important use than expanding a cemetery, Somervell said, launching into a deadpan comic tangent. “My hope is that we can make this a city for the living and not for the dead,” he said. “…If it is important to get dead ones in that area, I can guarantee you as many per acre in the building…as there would be otherwise.”

The general was likewise ready when asked about spoiling the view from the Lee mansion. “If there is anything inappropriate in standing on the steps of the home of the greatest soldier we ever produced in this country and looking at the War Department, I do not know what it is,” he said

It was a tour de force presentation, and Clarke knew it. The fine arts chairman asked to speak again and did his best to belittle the general. “The Commission of Fine Arts has been thinking about the problem of the development of Washington for 30 years. General Somervell has been thinking about it for, maybe, 6 months. It seems inconceivable to me…”

Somervell angrily interposed. “Do you not think you had better stick to what you have been doing yourself?” he snapped at Clarke.

Clarke ignored the interruption and again pushed for the quartermaster depot site. “The general passed that off to say that he does not want to place the War Department around some Negro shacks,” he said. “Well, it is not going to be very long before the improvement of the War Department building will eradicate any of the objectionable buildings that are in the vicinity of the site.”

Somervell was incensed by Clarke’s comments. In the hallway afterward, Clarke saw Somervell. He walked over to the general, greeting him with his hand extended. Somervell refused to shake it and walked away.

Clarke gloomily filled in waiting reporters on what had transpired. “It looks like the War Department is going to win,” Clarke said. “The only question remaining is esthetic, and the War Department can’t understand that.” As Clarke predicted, the subcommittee unanimously approved money for the building at Arlington Farm on August 11.

When the full Appropriations Committee considered the measure the next day, four dissenters spoke against the building, including Senator Theodore Green of Rhode Island, who considered the building “a monstrosity.”

But the only opinion that really mattered was that of Glass. At eighty-three, the committee chairman was a living link to antebellum Virginia, born in Lynchburg three years before the Civil War. Except for a stint as secretary of the treasury under Woodrow Wilson, Glass had represented Virginia in Congress since 1902, first in the House and since 1920 in the Senate. The little Democrat was known for his eloquent and fiery tongue. “When he barked at fools or knaves, it was spice to everybody but the victims,” a newspaper once wrote. Glass was virulently opposed to Roosevelt’s New Deal, calling it “a disgrace to the nation,” but he tended to back the president staunchly on defense matters. And like Representative Woodrum in the House, Glass saw Somervell’s building as an economic bonanza for his home state. “Carter Glass held the whole thing in the hollow of his hands,” a disgusted Harold Ickes wrote in his diary. “With $35,000,000 to be invested in his State this ‘grand old man’ would not be denied.”

Glass easily won the committee’s approval, though the Virginian denied any real role in its decision. “Some of you fellows have been writing about my influence with the committee, but I only talked in there about one-tenth of the time some of the other members talked,” he told reporters after the vote. Glass did not need to speak much. A mere scowl from the acerbic chairman was enough to cow the more junior members of the committee.

President Roosevelt was still at sea. Just a day earlier, a jaunty dispatch labeled “From USS Potomac” had been distributed to the press in Washington. “All members of party showing effects of sunning,” it read in part. “Fishing luck good.” In his absence, the Senate ignored Roosevelt’s request that the building’s size be halved. “The President’s hurriedly expressed admonition for caution, written just before he left Washington for a vacation, has been disregarded,” the

Star

noted dejectedly.

The opposition had thus far been too divided. Some thought the whole idea of a giant War Department building was ludicrous. Some opposed the size, but not the Arlington Farm site. Others opposed the site, but not the size. Some insisted the building should be put in the District, while others acknowledged that would be impossible and instead favored the quartermaster site. “The Army’s blitzkrieg attack on Congress and Washington, with the largest office building in the world as its immediate objective, has been so sudden and so overwhelming that effective resistance has been scattered,” the

Star

wrote. “Nothing quite like it has ever happened in Washington before.”

But in two days the measure would go to the Senate floor, where there were already signs of a real fight brewing. Senate Majority Leader Alben W. Barkley, the genial and eloquent Democratic warhorse from Kentucky, declared to reporters that he would “infinitely prefer” to see the building placed in Washington rather than Arlington. Somervell’s high-speed push had rankled some senators, including Harry Truman and other members of the Public Buildings and Grounds Committee, irritated that the War Department had not consulted them.

On top of that, Ickes publicly split with his absent president, issuing a statement declaring “such a vast structure” at Arlington Farm would “turn our parks into mere traffic ways and spoil the setting of such national symbols as the Arlington Lee Memorial and other monuments.” Ickes also sent a letter to Stimson August 12 warning that if the building should be erected “we would all live to regret it. It would be a blackmark against this Administration and a discredit to the Army. And so I, for one, protest.” Stimson politely but insistently defended the building. “The plan for Washington cannot be a fixed, inflexible affair which will not meet the needs of the Government,” Stimson replied, calling the building an “urgent necessity.”

The odds looked in favor of Somervell and his building, but the general complained about the fuss. “It’s all gummed up,” he groused to a group of reporters. “Well, you newspapers have so many engineers and architects who know better than the Army, you’ve got us in a hell of a mess with Congress.”

Most shockingly extravagant proposal

The Reverend Barney T. Phillips, rector of the Church of the Epiphany in Washington, opened the Senate session on the afternoon of Thursday, August 14, 1941, with a prayer: “In these fateful days, bind us with that bond of earnest devotion which portends freedom and emancipation, that we may yoke life’s hostile forces to the loving purposes of God.” It was a fateful day, certainly. Senator Barkley took the floor to incorporate momentous news into the Congressional Record: the Atlantic Charter, a joint statement from the president of the United States and the prime minister of Great Britain just released that morning. The secret meeting at sea had been revealed to the world. The charter was a statement of principles whose meaning had only begun to be debated, but the impression left was unmistakable: America and England were bonded in a struggle to end Nazi tyranny.

Discussion on the Senate floor immediately turned to the matter of the day, the $35 million War Department building. Barkley eloquently expressed his reservations. “I cannot divest myself of the feeling that in building up the Capital of the Nation we should have some idea of and some respect for beauty and symmetry as well as utility,” he said.

The diminutive senior senator from Virginia rose in defense. The evidence presented to his committee, Carter Glass told the Senate, had demonstrated “that the building is urgently needed immediately [and] that if any other site were selected there would be long delay.” The Senate had the assurances of Somervell that the building “would not detract in the slightest degree from the beauty of that section,” Glass said.

The floor was not full—many senators were absent from Washington in the middle of August—but the two-hour debate that followed was bruising: “a first-class battle,” in the words of the

Star.

A steady stream of senators, Democrats and Republicans alike, assailed the building. “If we take this step today, because of the argument of haste, we will rue it and regret it for many years to come,” warned Senator Abe Murdock, Democrat of Utah.

Frustrations poured out about the cavalier manner in which Somervell and the War Department had proceeded. “It is not so long ago that persons were charging the War Department was without imagination,” said Senator Francis Maloney, Democrat of Connecticut. “Someone at the War Department…must have heard that and decided that hereafter they would leave nothing to the imagination…. Here we have—and heaven knows where it came from—plans already drawn, without consulting the Congress, plans for the world’s largest office building.”

Arthur Vandenberg, the formidable Republican from Michigan, attacked the “shocking” size. “Unless the war is to be permanent, why must we have permanent accommodations for war facilities of such size? Or”—Vandenberg added to laughter—“is the war to be permanent?”

Senator Pat McCarran, Democrat of Nevada, warned that permitting the War Department to move to Virginia would unleash an exodus of federal agencies moving out of the capital. “Is there any reason why the Department of Agriculture should not be built in Iowa?” asked McCarran. He introduced an amendment requiring that the building be erected in the District of Columbia.

As Representative Woodrum watched nervously from the rear of the chamber, fellow Virginian Glass stood a second time to put down the insurrection. He insisted that thorough investigation had shown there were no adequate sites in the District of Columbia. McCarran’s amendment failed 20 to 28. It was the closest call yet for Somervell’s plan. A change of five votes would have forced the War Department to build in Washington, a requirement that quite likely would have derailed the whole project.

The fight was not over. Robert A. Taft, the diehard conservative from Ohio and avowed enemy of all things Roosevelt, rose next to lead the sharpest attack of the day. “Mr. Republican,” as he was known, pronounced himself staggered by the building’s size. “To my mind, there is not any evidence that we shall need such a tremendous building, the largest office building that has ever been built in the entire world…,” he said. “It seems to me that in some ways this is the most shockingly extravagant proposal that has been put up to Congress….”

Taft offered an amendment to cut the $35 million appropriation in half, gleefully claiming he was acting in accordance with Roosevelt’s own stated desire to halve the building’s size. Taft’s somewhat disingenuous amendment would effectively kill the proposal, as half the funding would not buy half a building. Taft’s amendment failed, 29 to 21. Having weathered the assaults, House Resolution 5412, including authorization to construct the War Department building, finally passed.

Harold Ickes held Carter Glass responsible. “Adams and…other senators went along with him like sheep although some senators did make a spirited fight,” the secretary wrote in his diary.

The Washington Post

blamed Somervell’s rush tactics. “It is impossible to avoid the belief that Congress has been maneuvered into an unwise decision by the emergency circumstances under which this project has been considered,” an editorial sadly concluded.