The Pentagon: A History (42 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

Popular Science

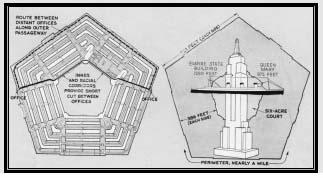

graphic from 1943 showing the shortest route between offices and comparing the relative sizes of the Empire State Building, an ocean liner and the Pentagon.

Able and fearless constructors

The Pentagon was still not finished in the New Year. Some five thousand construction workers remained on the job. They rushed to get the fifth floor ready for occupancy, and they tiled, painted, and plastered the basement. Outside, crews poured the last of the road network, battling cold weather. John McShain had a theory as to why it always seemed impossible to finish a job: Construction crews had a built-in bias against completing the work and losing their jobs. “If you want to finish on time, fire everybody, and bring a whole new crew in,” he told Bob Furman. McShain was joking, but only just.

The goal of completing the building by November 15 had long since been abandoned, pushed back to January 1, 1943, because of the additional fifth-floor work. Following a visit to the Pentagon on New Year’s Day, Groves reported to Fat Styer, Somervell’s deputy, that work would be completed by January 15. Official construction progress reports record the building as “substantially complete” by January 15. This has been adopted as the Pentagon’s official completion date, recited in fact sheets, and used to mark the building’s anniversary.

Yet “substantially complete” was not the same as finished; records show the building was not quite done by January 15, and thousands of employees had yet to move in. The main holdup was installing pipes for the heating and air-conditioning on the fifth floor; War Department employees could not move in until it was done. Steam fitters and mechanics needed for the job were in such short supply that McShain was scouring other cities for available workers. By January 9 Groves had postponed completion to February 1; on January 14 McShain told Groves they would not meet this date either. “While we have every desire to meet your request and complete the building by February 1st, we are of the opinion that it is a physical impossibility to accomplish this date,” McShain wrote. He promised they would finish by February 15. This they did.

Whether the official completion date is considered to be January 15—some sixteen months after ground was broken, or February 15, seventeen months after—is of little import. Either way, it was a stunning accomplishment.

The auditor from Harold Smith’s Bureau of the Budget, so appalled at the design, scale, and cost of the building, nonetheless tipped his hat to the builders. The speed with which the Pentagon was built “unmistakably indicates that the men responsible for this project were able and fearless constructors possessed of a large fund of amicability and common sense,” he wrote.

Able and fearless they had been—Somervell, Groves, Renshaw, McShain, and Hauck chief among them.

The Pentagon

In the Pentagon, the War Department now had a headquarters that was four times the size of the British War Office at Whitehall, the German Kriegsministerium in Berlin, and the Japanese General Staff headquarters building in Tokyo—combined.

Originally proposed to have 5.1 million gross square feet, cut to 4 million square feet by groundbreaking, the official tally as 1943 dawned was calculated to be 6.24 million gross square feet. The Pentagon also included more office space than previously thought. Instead of the 2.3 million net square feet of office space figured the previous fall, the engineers calculated that 3.6 million net square feet could be occupied, once the fifth floor, the conversion of the basement from storage to offices, and other alterations were included. Its massive size told of the vast scale of the American war mobilization, as well as the U.S. Army’s reliance on a huge staff—not to mention the overwhelming force of Somervell’s personality.

In short order, Somervell had conceived and built an institution that would rank with the White House, the Vatican, Buckingham Palace, and a handful of others as symbols recognized around the world, a building in whose name pronouncements were made and declarations issued. At a price of about $75 million, more than twice what Somervell promised, the building also represented the Pentagon’s first cost overrun.

Upon its creation, the massive concrete building assumed an aura of permanence that made it seem as if it had always been there—“a large geometrical form existing almost beyond time or place,” in the words of architectural historian Richard Guy Wilson.

On February 12, 1943, Major General Alexander D. Surles, chief of the Army’s Bureau of Public Relations, sent a memorandum to Marshall’s office concerning the official designation of the new War Department headquarters:

1. As time goes on the permanent home of the War Department will occupy a place of increasing dignity and distinction in the Nation’s history. The building will be world-famous and its name a household word.

2. It has been suggested that the designation, “The Pentagon,” would be more in keeping with this historical character than the one now in use, “The Pentagon

Building.

”3. It is recommended that the building officially be designated as “

The Pentagon.

”

Not everyone was taking the building’s name so seriously; Roosevelt, ever the punster, had taken to calling it “the Pentateuchal Building,” a reference to the first five books of the Old Testament. The president’s quips notwithstanding, Stimson’s office approved Surles’s recommendation on February 15, and “The Pentagon” was made the official name by a general order signed by Marshall on February 19.

Surles’s memorandum was striking for saying the Pentagon would be the permanent home of the War Department. This was entirely contrary to official policy, which was that the War Department would move back to Washington after the war. Surles had recognized a truth that nobody in the Army was saying publicly: They would never abandon the Pentagon.

The miraculous takes a little longer

The focal point of the Pentagon was above the River entrance of the building, on the third floor of the E Ring, where Stimson and Marshall’s suites lay and where momentous decisions would soon be made. At the Casablanca conference in January 1943, Roosevelt—to Churchill’s surprise—had publicly declared that the Allies were fighting a war that would end only in the “unconditional surrender” of Germany, Italy, and Japan. Returning from Casablanca on January 29, Marshall set to work with Stimson to chart the path. Of immediate concern, operations in North Africa were at a standstill and tough fighting lay ahead in Tunisia. Marshall was determined to find ways to help Eisenhower deal with mounting military and political crises. At the same time, preparations were needed for the next step, advancing on Italy via an invasion of Sicily, which Marshall had agreed to despite his misgivings about getting bogged down in the Mediterranean. Plans were also in the works to recapture Burma, overrun by the Japanese in the spring of 1942. Overriding everything else were decisions to be made about the cross-Channel invasion of western Europe from England—Operation Overlord, now set for 1944.

Marshall’s routine at the Pentagon was already well established. He was picked up from Quarters One at Fort Myer at 7:15

A.M.

in an Army Plymouth for the short drive around Arlington Cemetery to the Pentagon. At Marshall’s order, the driver often would stop to pick up young Army officers or other war workers left stranded by overcrowded buses; the shocked riders would be quizzed about their jobs by the chief of staff during the rest of the trip to the Pentagon. At the River entrance, the driver would take Marshall down a ramp leading into a garage beneath the building, pulling up to a door that led to the private elevator he and Stimson shared. (One predawn morning, when Marshall stopped by without his building pass on his way to go duck hunting, the guard at the elevator would not let him in, failing to recognize the man in the hunter’s garb.) Marshall preferred taking the private elevator up from the garage directly to his office to avoid wasting time with hallway chatter. This drove Marshall’s staff to distraction, as they could never be quite sure when the general had arrived.

Early on the agenda every morning was a briefing on the situation with U.S. forces around the globe, with much of the emphasis these days on operations in North Africa. There was a minimum of ceremony; Marshall was usually joined by Hap Arnold, commander of air forces, Major General Thomas T. Handy, head of the operations division, and often Somervell. The briefing officers, who had been at the Pentagon all night reviewing the message traffic coming into the Signal Center and communicating with all the theaters, would speak for ten or fifteen minutes. Marshall would often make decisions on the spot. “A question would come up and you could get the general’s thinking on it right then and go on and do something about it,” Handy recalled. Even if there was no immediate answer, the policy was to get back to the theater within twenty-four hours with some kind of reply while the issue was further investigated.

Stimson often would come visiting soon afterward. The door connecting his office to Marshall’s was never locked—one measure of the enormous respect and trust the two men had for each other—and the secretary would walk in two or three times over the course of the morning to consult. Two other doors led into the chief of staff’s office, further complicating the task of keeping track of who was in the room.

Marshall’s office, Room 3E-921, served as a de facto conference room, with a half-dozen leather chairs spread about. A succession of officers came in and out, sometimes stacking up in the tiny anteroom outside Marshall’s office as they awaited a chance to go in. Peering into Marshall’s office to see if the general was available was a serious mistake. Marshall hated being spied upon, and anyone poking his head in would be met with a stern order to enter the room. A junior officer might find himself stating his business before Marshall and a half-dozen generals. Marshall soon pasted a three-by-five card on the door leading from the anteroom with a warning: “Once you open this door, walk in regardless of what is going on inside.” That eliminated most of the peeking.

Somervell was a frequent visitor to the command suites, enjoying close if formal relations with Marshall and Stimson. He had, of course, ensured that the headquarters for his Services of Supply (SOS) was not far from the seat of power. Somervell’s office, Room 3E-672, set grandly atop the Mall entrance to the building, was in the next section of the E Ring, on the same floor as Marshall and Stimson. Somervell kept two telephones on a side table within arm’s reach of his desk, and a door in his office led to a soundproof room with four secure, direct-line telephones, including one to the White House. In many respects the Pentagon was Somervell’s building, and not just because he was responsible for its creation: His enormous Army services organization occupied just over half of the Pentagon’s office space. By comparison, the Office of the Secretary of War and the Office of the Chief of Staff, including the entire general staff, occupied 22 percent of the building, and the Army Air Forces 11 percent.

There was no downtime in Somervell’s office. “He streaks through the day like a Lockheed Lightning,” recounted a reporter who spent a day with the general. Within five minutes of arriving in his office, Somervell had “pressed down every buzzer in sight” to summon aides. His top officers—among them his deputy, Fat Styer, and a talented brigadier general named Lucius D. Clay—came in frequently to confer and study oversize wall maps in Somervell’s office. One showed the United States, the other the world, and they were covered with a forest of yellow, blue, and white pins, each representing a different SOS project.

When Somervell’s temper flared—generally a dozen times a day—he would jettison his gracious manner, drop his voice even lower than normal, and tug agitatedly at his neatly clipped mustache. His latest method to try to control his temper was to go into another room, walk violently back and forth, and return with an unconvincing smile on his face. Somervell had given up cigarettes in the summer of 1942 and preached against smoking with the zeal of a convert, but on stressful days his secretary, Katherine King, would find billowing clouds of smoke in his office. As Somervell figured out the logistics for supplying the North Africa campaign, he hurled invectives about “bathtub admirals” and “knotty-pine powder-room strategists” or anyone else slowing him down. Occasionally Somervell had reason to regret his outbursts—he publicly raged about “golf-playing industrialists” after being unable reach one on the telephone the previous summer and since then had been forced to give up his favorite sport, fearing it would be unseemly if he were spotted on a golf course.

On the wall of Somervell’s office was a framed photograph of his hero, Teddy Roosevelt, and a sign bearing the words that Somervell had popularized as the Services of Supply motto: “We Do the Impossible Immediately. The Miraculous Takes a Little Longer.” Somervell and the SOS were proving it to be more than a slogan.

Attending the Casablanca conference in January with Marshall, Somervell learned that Eisenhower desperately needed more trucks and other equipment. Somervell quickly contacted Styer at the Pentagon, dispatching a cablegram “as long as a book” listing equipment to be sent immediately to North Africa: trucks, locomotives, boxcars, tank engines, carbines, artillery sights, machine guns, tractors, and road equipment, among other items. The staff in Somervell’s office, well versed in their master’s ways, “settled down to furious days and sleepless nights.” Across America, wires hummed, orders were typed, trains rolled, and cargo planes flew. Somervell told Eisenhower he would have 5,400 trucks at U.S. ports in three days, ready to be shipped. The arrival of the trucks three weeks later—“which by the way won the Africa campaign,” Eisenhower later said—enabled the commander to keep his battlefront supplied and to transfer troops rapidly around Tunisia to fight the forces of German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. When all the trucks and equipment had been sent, an exhausted Styer sent a plaintive message to Somervell, still in Casablanca: “If you should happen to want the Pentagon shipped over there, please try to give us about a week’s notice.”