The Pentagon: A History (52 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

The zeal to show tolerance, however admirable, had created an atmosphere in which appearances were more important than practicality. Most troubling was the convoluted command structure. General O’Malley was the operational commander, but in name only. General Johnson retained overall military command, including any decision to load weapons, fix bayonets, or use tear gas. Yet Johnson had little authority himself. McNamara retained the final decision on the use of force. “I told the president no rifle would be loaded without my permission, and I did not intend to give it,” McNamara later wrote. At the insistence of the White House, the attorney general’s approval was needed not only for making arrests but also for committing the reserves hidden in the building. Civilian direction was supposed to be shared by McGiffert and Deputy Attorney General Warren Christopher, who would be positioned at the Pentagon, but decisions on the use of force and reinforcements would have to be cleared by Attorney General Clark, the overall coordinator of the federal response, over a hotline connecting the operations center to the Department of Justice command post in Washington. O’Malley had less power than a traffic cop.

The day before the march, at 4:45 on Friday afternoon, General Johnson brought all the military commanders together in the Army Operations Center. Johnson was a tough, spare North Dakota native, a West Point graduate with little political tact. Taken prisoner by the Japanese in the Philippines in 1942, Johnson survived the Bataan Death March, weighing ninety pounds upon his liberation in 1945. He had seen some of the toughest fighting in Korea, from the Pusan breakout on, and had been awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for extraordinary heroism. Johnson was not particularly worried about the demonstrators descending on the Pentagon.

The Army chief of staff told his commanders that he had met with McNamara and the service secretaries, and the message was clear: “This is looked upon as fundamentally a public relations problem,” Johnson said.

The situation became extremely fluid

A vast cross-section of America came marching across Memorial Bridge toward the Pentagon on the afternoon of Saturday, October 21. More than fifty thousand people had rallied late in the morning at the Lincoln Memorial for speeches and songs, though not all continued to the Pentagon. Claims by organizers of 100,000 or more marchers notwithstanding, counts made by two intelligence agencies of the number of protesters crossing the bridge—and corroborated by analysis of high-resolution photographs made by a Navy Skywarrior reconnaissance plane—put the figure closer to 35,000. It was by any measure an impressive and powerful showing, far exceeding any Pentagon demonstration before or since.

The great majority of marchers were intent on a peaceful demonstration; for many it was an act of conscience against a war they deeply opposed; for others it was simply a lark, a chance to join in the excitement of a youth movement challenging authority and promising free love. A much smaller but not insignificant number of marchers were intent on destruction. Army intelligence concluded after the march that there had been “probably fewer than 500 violent demonstrators; however these violent types were backed by from 2,000 to 2,500 ardent sympathizers.” The actions of this hardcore minority would dominate the day and form the lasting impressions of the march.

Marching at the front, arms linked, were prominent antiwar demonstrators including Dave Dellinger, Jerry Rubin, Norman Mailer, the poet Robert Lowell, and Benjamin Spock, the beloved pediatrician and author of books on raising babies (an Army report noted with suspicion that he advocated “permissive child rearing”). Great cheers greeted a contingent of veterans of the Lincoln Brigade, who had fought the fascists in Spain and now marched carrying a sign reading “No More Guernicas.” The crowd was mostly young, with sizable contingents of middle-aged and older protesters. Many of the college students looked as if they were dressed for a homecoming football game, the men in tweed jackets and flannels, the women in stylish skirts and stockings. Long-haired hippies wearing love beads and leather bells lent a colorful shade to the crowd.

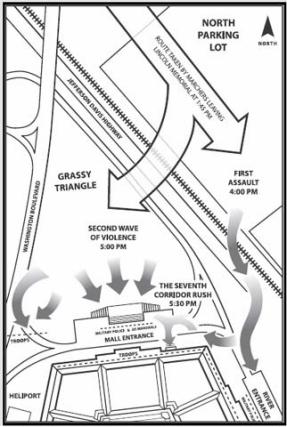

High on spirit but low on organization, the marchers started and stopped their way across the bridge with excruciating slowness beginning about 1:45. Arriving in Virginia, Mailer got his first glimpse of the Pentagon, which he likened to the five-sided nozzle on a can of antiperspirant, “spraying the deodorant of its presence all over the fields of Virginia.” The demonstrators marched through the fields of the old Arlington Farm and on to the concrete fortress. The route marked by police channeled marchers into the North parking lot, where a platform had been set up for speeches at a spot more than a thousand feet from the Pentagon, separated from the building by an eight-foot chain-link fence, a four-lane roadway, an abandoned railroad line, and an embankment. Protesters were also allowed to assemble on a large grassy triangle much closer to the building, directly below the raised Pentagon Mall plaza. But access to the grassy area was not clearly marked, and many arriving marchers were under the impression they were fenced off from the building. Demonstrators, Mailer among them, milled about in confusion, unsure of where to go or what to do. “No enemy was visible, nor much organization,” he wrote. “[T]he parking lot was so large and so empty that any army would have felt small in its expanse.”

Walter Teague and several hundred militants from a group known as the Revolutionary Contingent had a distinct purpose in mind. After crossing the bridge, they tore off from the main body and raced toward the building. Teague, a thirty-one-year-old New Yorker and tough veteran of the radical movement, wearing a white crash helmet on his head and a gas mask strapped to his side, ran at the forefront, flanked by two demonstrators carrying fifteen-foot staffs with the red, blue, and gold flag of the Viet Cong. “Our specific goal was to create a confrontation—a nonviolent one, because they were military and we were not—and make a physical effort to get into the Pentagon,” Teague recalled nearly forty years later. Scouts dispatched by Teague found—or created—a gap in the roadway fence that separated the North parking lot from the Pentagon, and they ran for it. At 3:59, a call came in to the Army operations center warning that at least two hundred demonstrators, some armed with ax handles and gas masks, had broken through the fence and were charging the River entrance, which had been left even more lightly guarded than the Mall.

Chanting “Viva Che!”—Guevara, the Latin American revolutionary, had been captured and executed in Bolivia two weeks earlier—the shock troops rushed toward a line of a dozen MPs, who waited with their riot sticks held high. Teague called for his colleagues to slow down and link arms. The first row of demonstrators slammed into the soldiers, and the Battle of the Pentagon was on. A protester swung a picket sign at a soldier, a U.S. marshal grabbed a Viet Cong flag, and an MP clubbed a protester in the back. More demonstrators followed the lead of Teague’s shock troops and rushed through gaps in the fence; as the crowd grew, it flowed toward the Mall entrance and was soon pressing at the rope barrier.

It was quickly apparent that the whole low-profile strategy had backfired. Rather than somehow mollifying the advancing protesters, the sight of the Pentagon guarded by a thin green line seemed only to encourage those intent on attacking the building. “The low visibility philosophy may have developed an air of over confidence on the part of demonstrators and encouraged violence,” an Army report written soon after the march concluded. Teague, for one, was both surprised and relieved there were not more soldiers protecting the Pentagon.

O’Malley, the operational commander, recognized instantly that his men were in trouble, and at 3:59 requested reinforcements from the building to block the demonstrators. Minutes later, Johnson, McGiffert, and Christopher agreed to send troops to the River entrance and the Mall plaza. But the reinforcements could not be dispatched until approved by Attorney General Clark across the river in Washington. The call was made and they waited.

From his office window, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Nitze watched with alarm as demonstrators advanced below on the River entrance. At 4:03 he called McGiffert. “What gives?” Nitze asked. “Are you going to let them come up there?”

The crowd at the Mall plaza was likewise surging, and at 4:12 demonstrators on one side broke through the useless rope barrier and began shoving MPs. Still no approval had come from Clark, and no reinforcements were allowed out of the building, despite the rapidly deteriorating situation. Five minutes later, at 4:17, the operations center received Clark’s O.K. A minute later—nearly twenty minutes after O’Malley had initially requested them—soldiers came running out of the building, some with sheathed bayonets fixed to their M-14 rifles. They were able to contain the crowd, and demonstrators who did not fall back were arrested by U.S. marshals.

Soldiers were not supposed to fix bayonets without Johnson’s authorization, which the chief of staff had not given; subordinates later blamed the confusion on the stress of the moment but did not pretend to be apologetic about it. “The vision of the fixed bayonets by the incendiary demonstrators was regarded by many as a psychological plus in containing the restive crowd,” an Army report said. McGiffert, though, was unhappy when he saw the sheathed bayonets on television monitors. “This is not in accordance with instructions,” McGiffert complained to Johnson. At 4:25, Johnson ordered the bayonets removed.

The violence was kept momentarily at bay, but the twenty-minute free-for-all had emboldened the crowd and encouraged a sense of anarchy. “From this point on, the situation became extremely fluid,” an Army report said. More protesters moved up, many not looking for trouble but soon caught up in the chaos.

At the rope barriers, a small but vocal group of demonstrators—usually those hiding several rows back—taunted and abused the troops. “They spat on some of the soldiers in the front line at the Pentagon and goaded them with the most vicious personal slander,” James Reston of the

New York Times

reported. Others pelted troops with eggs, overripe tomatoes, fish, and plastic bags filled with beef liver. The soldiers, under orders to hold the line but left without masks or protective shields, made easy targets.

Captain Phil Entrekin, the commander of the 6th Cavalry’s 1st Squadron, C Troop and a Vietnam veteran, considered the lack of protection afforded his soldiers the “dumbest decision” he would see in more than twenty years with the Army. “Our kids were standing there and having all kinds of things thrown at them, to include feces,” he recalled.

Ernie Graves, accompanying Secretary of the Army Resor and other senior Army officials inside the Pentagon as they monitored the demonstration, was burned up by what he saw. “My own personal reaction was that it was somewhat of a travesty to put these soldiers out there in what I saw as a disadvantageous position and let these people abuse them,” Graves said. “I frankly thought it was cowardly.”

Out, demons, out!

Elsewhere, the crowd was more entertaining than ugly. Abbie Hoffman, wearing a tall Uncle Sam hat, went about his effort to levitate the Pentagon, but did not get far. He and his wife, Anita, split their last tab of LSD, held hands, and approached the building until they were stopped by MPs. “We’re Mr. and Mrs. America, and we declare this liberated territory,” Hoffman cried.

Nearby in the North parking lot, from atop a flatbed truck equipped with a sound system, musicians sounded an Indian triangle and a cymbal. They were “The Fugs,” an underground music group from New York assisting with the levitation. Coming upon the scene, Mailer described them in their orange, yellow, and rose capes, as looking “at once like Hindu gurus, French musketeers, and Southern cavalry captains.” The Fugs offered a sing-song litany of exorcism, chanting “Out, demons, out!” for a full fifteen minutes. A supporting cast of flower children sang their own hopeful incantations.

The Pentagon, by most accounts, did not move.

Hippies danced up to the lines of soldiers and placed flowers in the muzzles of their rifles. Some soldiers shook out the flowers, but one young soldier stayed motionless, unsure what to do. His sergeant solved the problem. “Jones, get that fucking flower out of your muzzle,” the sergeant ordered.

Mike Jenkins, Peter Jenkins and Brad Goodwin

The march on the Pentagon, October 21, 1967.

Some women went about trying to convert the soldiers, flirting with them or making impassioned if ponderous antiwar arguments. Others were simply crude and mocking. Some women tested the soldiers’ resolve by trying to unzip their flies; one coarsely propositioned the troops, promising to take them to the bushes if they would drop their rifles. “Of course, none of the soldiers said anything,” wrote Allen Woode, who witnessed the episode. “So, after trying this with several of the boys, she left, calling them all machines and fascists and fairies, and feeling smug.” One young woman grabbed the groin of one of Captain Entrekin’s C Troop soldiers; he reflexively butted her with his rifle, and she fell to the ground bleeding from her head. It was a violent sight that shocked soldiers and protestors alike.