The Pentagon: A History (62 page)

Read The Pentagon: A History Online

Authors: Steve Vogel

At 10:38

A.M.

, Schwartz sounded the all-clear, ending the evacuation twenty-five minutes after it started. Between the two evacuations, rescue workers had had little time to fight the fire or look for survivors in the one hour since the plane had hit the building. Combs and Schwartz—who would perform heroically through the ordeal—were blameless. They had acted responsibly on information Combs had confirmed from a second source. The evacuation for the phantom plane—and two more false alarms over the next twenty-four hours—“extracted a serious toll in terms of the physical and psychological well-being of responders,” a federal after-action report on the emergency response concluded. “These evacuations also interrupted the fire attack and changed on-site medical treatment of injured victims during the crucial early stages.” Whether the evacuations cost any lives is unknown. “I really can’t say if there was anybody in there whose life hung in the balance,” Schwartz later said.

The evacuation was just one of several grave miscommunications involving United Flight 93. Air Force F-16s under command of NORAD had scrambled from Langley Air Force Base in southeast Virginia at 9:30

A.M.

and were high over the Washington area by 10:10

A.M.,

but the pilots had been told they did not have shootdown authority. Meanwhile, no one in the National Military Command Center at the Pentagon or at NORAD headquarters was even aware that the D.C. Guard F-16s from Andrews were over Washington with authorization to shoot down passenger jets. Cheney apparently thought his shootdown instructions were being relayed to the NORAD jets and later told the 9/11 Commission he did not know that fighters had been scrambled from Andrews.

Had brave passengers aboard United 93 not staged a revolt against the hijackers that ended with the crash in Pennsylvania, the plane would likely have reached Washington by 10:23

A.M.

At that time, the F-16s from Langley lacked authority to shoot down the plane, and the F-16s from Andrews were not yet in the air. The 9/11 Commission wrote, “We are sure the nation owes a debt to the passengers of United 93.”

Tell me exactly where it hit

Lee Evey pulled into the Wendy’s on I-81 just south of the Virginia-Tennessee border for lunch on September 11. His brother-in-law had died the day before, and the Pentagon renovation chief had been on the road for six hours with his car radio and his two cell phones turned off, driving to North Carolina for the funeral.

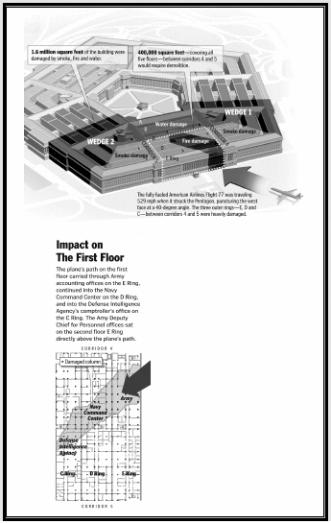

No one was at the counter at first, but then ashen-faced employees came from the backroom and told him the news. Evey raced back north, talking into both cell phones at once. “Tell me exactly where it hit,” he instructed his deputy, Michael Sullivan. The jet had cut diagonally through the newly renovated wedge and then continued into Wedge 2, Sullivan told him.

The plane’s path.

From a purely analytical perspective, the plane had hit the building in the best possible place. First, both wedges were only partially occupied. About a fifth of the offices in Wedge 1 were still vacant. Meanwhile, about two-thirds of the occupants of Wedge 2 had moved out in preparation for the next phase of renovation. Instead of the 9,500 employees who might have been there, about 4,600 employees occupied the two wedges at the time of the terrorist strike. Of those, about 2,600 were in the immediate impact area. Moreover, the plane had hit an area with no basement. If there had been one under the first floor, its occupants could easily have been trapped by fire and killed when the upper floors collapsed.

The plane struck the Pentagon just to the right of an expansion joint, one of the gaps left in the concrete work from the original design of the building to allow expansion or contraction from temperature changes. When the building collapsed around the impact point, the concrete broke cleanly at the expansion joint, saving the area to the north. It was another stroke of enormous good fortune, one that undoubtedly saved lives.

The hijackers had not hit the River or Mall sides, where the senior military leadership had been concentrated since 1942. Rumsfeld had been sitting in the same third-floor office above the River entrance as every secretary of defense since Louis Johnson in 1949, a location that had been a matter of public record all that time. The joint chiefs and all the service secretaries were arrayed in various prime E-Ring offices on the River and Mall sides. All the command centers save the Navy’s were on the River or Mall sides; the National Military Command Center could have been decimated as the Navy Command Center was, a disaster that could have effectively shut down the Pentagon as the first American war of the twenty-first century began.

The plane, ironically, had struck the first section of the Pentagon occupied in the spring of 1942. Marjorie Hanshaw Downey, the Iowa girl who had moved in then with her fellow War Department plank walkers, wept in her suburban Maryland apartment as she watched television that day and realized the area she had occupied nearly sixty years earlier been hit. “It really hurt when I saw that,” she recalled. “Not only for the people, but what it did to our country.”

Most remarkably, the plane had hit the only renovated wedge. The renovators had started their work in the same place as the original constructors. The plane had hit the only place where the exterior wall had been reinforced with steel; the only place ballistic cloth had been hung to catch blast shards; the only walls with blast-resistant exterior windows; the only wedge with sprinklers.

Years of work had gone up in flames, but Evey felt overwhelming relief when Sullivan told him where the plane had hit. The costly improvements had bought priceless protection and time for the thousands who managed to escape.

I’m not running anymore

The plane’s path did not strike Phil McNair as good fortune. Leaving the center courtyard, he had walked out a corridor to the South parking lot. He was soaking wet and black with soot, unable to talk from the smoke he had inhaled. McNair walked around the building until he came to the smoking hole where his office had been. The plane had hit almost directly below the office of his commander, Lieutenant General Tim Maude, the Army’s chief of personnel. One look, and McNair knew there was no hope for most of his people. He knew where he had been, and, seeing the devastation, he knew that anyone who had been closer than he had been had to be dead.

A nurse saw McNair, standing unsteadily, gazing at the wreckage. She grabbed him. “Are you okay?” she asked.

“Yeah,” McNair croaked. “I could use a little oxygen.” Within minutes he was in an ambulance on his way to Arlington Hospital with dangerous levels of carbon monoxide in his blood. Ambulances had already rushed Paul Gonzales and Kevin Shaeffer to Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, their drivers swearing and driving off-road to get around horrendous traffic. Gonzales would soon be on life support after his lungs failed. Shaeffer had burns over 42 percent of his body, and in the emergency room he overheard a nurse assessing his chances as fifty-fifty. Shaeffer grabbed her and pulled her close. “No! I’m alive!” he gasped. “I’m going to live!”

They had made it out alive, but by then it was obvious to Arlington Fire Captain Mike Smith that no one else would. Firefighters had regrouped after the evacuation for the phantom airplane and were making a new assault on the blaze, which had intensified in their absence. The young firefighters in Smith’s crew were taken aback by what they saw. Smith was one of the anchors of the fire department, solid and even-keeled, a captain whom other firefighters would follow anywhere. “Listen, the key is we’re going to stay together and we’ll stay safe,” Smith told them. But he was worried too.

It was unlike any fire Smith had fought in thirty years. Jet fuel had splashed deep into the building and ignited raging fires. Later measurements indicated the fire reached 1,740 degrees Fahrenheit, a temperature similar to that in the twin towers. The intensity of the fire was forcing crews out of some areas. Protective clothing shielded the firefighters from the fire, but Smith felt as if he was in an oven.

Smith looked up through a ventilation shaft and could see big fires burning through the second and third floors. They were spreading up into the fourth and fifth floors and then the roof. A thick layer of roofing wood beneath the slate was soon burning out of control, protected by the concrete below it and the slate atop it. Up on the roof, exhausted firefighters cut trenches across the slate roof to break the path of the flames, guessing where to breach ahead of a fire they could not see.

Those watching the scene on television and those standing in front of the building had a deceptive view of the scope of the disaster. The Pentagon’s very size distorted the perception, even among emergency officials, at first. The 80-foot gash on the building’s face was a relatively short gap in the 921-foot wall. But the rescue workers inside found an entirely different reality. “Huge heaps of rubble and burning debris littered with the bodies and body parts…covered an area the size of a modern shopping mall,” the federal after-action study said. Smith knew from training that a high-impact airline crash decimated a body, but that was no preparation for seeing it on this scale. “It was just a horrible, horrible scene.”

The five-story collapse zone in the E Ring was surrounded by damaged areas extending hundreds of feet, where columns and supports had been blown out and floors were sagging and in danger of further collapse. Structural specialists dispatched by the Federal Emergency Management Agency feared the collapsed two-foot thick concrete roof was poised to slide onto rescue workers. As Smith’s crew moved deeper into the building, there were dead zones where his radio was not picking up any traffic. “I didn’t have the safety of feeling like someone really knew where we were,” he recalled.

At 2

P.M.

the evacuation tone sounded and all rescue workers were pulled out again; the control tower at National Airport warned of an “inbound unidentified aircraft.” Smith heard the tone and left the building but sat down on the back of his fire truck and refused to go farther. “Well, if they’re going to crash something, they’re just going to get Mike today,” he said. “I’m not running anymore.” It turned out to be a plane carrying Attorney General John Ashcroft. Firefighters were furious.

After the all-clear, Smith and his crew attacked the fire, but the exhausted firefighters were replaced at 4

P.M.

by fresh teams. They had each gone through four bottles of oxygen—one was usually enough even for a big fire—and the fire was still out of control. Smith and his dehydrated crew were put on IVs and taken to the hospital.

As Smith had feared, rescuers were not finding anybody alive. A FEMA urban search-and-rescue unit had been hunting through the rubble with dogs since early afternoon, with no success. Everybody the dogs found was dead.

Out front, Lieutenant Colonel Ted Anderson had given up hope. “There were hundreds of us just waiting with backboards, because we figured at some point we were just going to start dragging the dead out,” he said. Late in the day, Anderson overheard fire commanders talking. A group of bodies—five, according to a later FBI evidence report—had been found clustered in the first-floor E Ring corridor, about forty feet from the emergency exit where Anderson had tried to go back to pull more people out. Whether they were the ones the man in flames had screamed were looking for a way out, no one knew.

They would have won

Inside the National Military Command Center, the smoke continued to build. The Arlington County Fire Department was pressing for everyone—Rumsfeld included—to evacuate the NMCC. Rumsfeld still refused to go to Site R, but he did consider moving his headquarters to one of three close-by locations: the White House, the Defense Intelligence Agency headquarters across the river at Bolling Air Force Base, or a third classified alternate command center nearby. Rumsfeld’s eyes were smarting and his throat was raw. “The smoke was a problem, but it was not killing people in the part of the building we were in at that moment,” he later said.

Rumsfeld decided the Pentagon would not be abandoned. Even on fire, the Pentagon was the best place from which to run the new war. “We had things to do and business to conduct and problems to solve, and we had the necessary people and capacity here to do it, and I decided we’d do it,” he later said. Beyond that, the decision was completely in keeping with the secretary’s personality. For better and for worse, Rumsfeld had a long stubborn streak; he was a former naval aviator and had the swagger to match. “I also didn’t like the idea of evacuating,” he said. “They would have won, the terrorists.”

Fire commanders decided to send a team to evaluate the smoke and knock down any fire threatening the command center. Firefighters assembled gear, chalked out a plan, and were ready to go, but then realized nobody knew where the command center was. Ted Anderson, hovering nearby, volunteered to take them in.

A battalion chief threw an oxygen tank on Anderson’s back and a mask on his face. A bus drove them around to the River entrance, and Anderson—wearing his oxygen tank atop his striped shirt and tie—led the firefighters to the command center. The entrance was guarded by machine-gun–toting Pentagon police officers wearing black uniforms and helmets. Inside, it was packed and hazy, and many were wearing medical masks. The firefighters measured the air quality and deemed it survivable. Exhaust fans were set up to improve the air flow. They checked the area and found no fire near the command center; instead, it was smoke from the crash scene that was wrapping around the building and getting in the intake vents. Steve Carter got a call on the radio and came up with a low-tech solution. When the smoke wrapped around to the vents, workers on the roof closed the dampers, and when it blew away, they opened them.

The smoke did not entirely dissipate, and communications remained unreliable, but the command center stayed open. Rumsfeld and Air Force General Richard Myers, vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs, shuttled back and forth between the command center and the Cables communication hubs upstairs, depending on how bad the smoke was, and with whom they needed to speak.