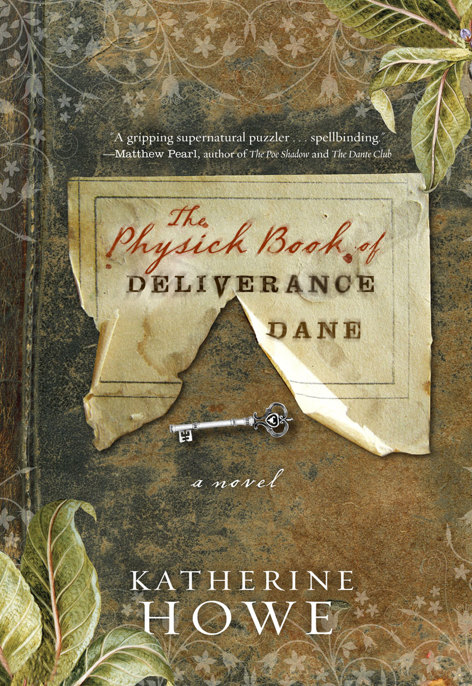

The Physick Book of Deliverance Dane

A Novel by

For my family

I watch’d to day as Giles Corey was present to death between the stones. He had lain so for two dayes mute. With each stone they tolde him he must plead, lest more rocks be added. But he only whisperd, More weight. Standing in the crowde I found Goodwyfe Dane, who, as the last stone lower’d, went white, grippt my hand, and wept.

—Letter fragment dated “Salem Towne, September 16, 1692”

Division of Rare Manuscripts, Boston Athenaeum

The Key and Bible

Peter Petford slipped a long wooden spoon into the simmering…

“IT WOULD APPEAR THAT WE ARE NEARLY OUT OF TIME,”…

SINCE ARRIVING AT HARVARD, THREE YEARS AGO, CONNIE HAD SHARED…

“I STILL CAN’T BELIEVE SHE DID IT,” SPAT CONNIE. SHE…

“THERE IS THE DISTINCT POSSIBILITY THAT IT COULD BE A…

“Explain this to me again,” said Sam, sliding a heavy…

CONNIE STOOD, ARMS FOLDED, BEFORE THE IMPOSING GREEK REVIVAL edifice…

THE SHOULDER BAG SLIPPED TO THE FLOOR WITH A DULL…

CONNIE STOOD IN THE CRAMPED LADIES’ ROOM ON THE FIRST…

“SO WHERE’D YA WANNIT?” ASKED THE MAN, PLOPPING HIS TOOL…

“HEY, CORNELL!” A VOICE SAID, AND THE WORDS FLOATED IN…

THE UPSTAIRS SPECIAL COLLECTIONS READING ROOM OF THE BOSTON Athenaeum…

“FRANKLY, I AM A LITTLE SURPRISED THAT HE WOULD CALL…

CONNIE TOOK A LONG SWALLOW OF HER COCKTAIL, AND WHEN…

DESPITE HER BEST EFFORTS TO FEEL AT EASE IN GRANNA’S…

The Sieve and Scissors

THE CARDS SPREAD ON THE DINING TABLE LOOKED LIKE A…

The wooden bench in the vestibule outside of Manning Chilton’s…

A CHIME SOUNDED, AND THE GREAT MASS OF HUMANITY IN…

THE BACKS OF CONNIE’S EYELIDS GLOWED RED, AND SHE BECAME…

NIGHT CAME UNDER THE TIGHT CANOPY OF VINES OVER GRANNA’S…

THE GUARD BARELY LOOKED UP AS CONNIE FLASHED HER LAMINATED…

THE SURFACE OF THE DINING TABLE WAS SPREAD OUT WITH…

CONNIE EASED THE HANDLE OF THE HOSPITAL ROOM DOOR DOWNWARD,…

THE LONG DINING TABLE STOOD CLEARED OF ITS USUAL FLOTSAM,…

Marblehead, Massachusetts

Late December

1681

P

eter Petford slipped a long wooden spoon into the simmering iron pot of lentils hanging over the fire and tried to push the worry from his stomach. He edged his low stool nearer to the hearth and leaned forward, one elbow propped on his knee, breathing in the aroma of stewed split peas mixed with burning apple wood. The smell comforted him a little, persuading him that this night was a normal night, and his belly released an impatient gurgle as he withdrew the spoon to see if the peas were soft enough to eat. Not a reflective man, Peter assured himself that nothing was amiss with his stomach that a bowlful of peas would not cure.

Yon woman comes enow, too

, he thought, face grim. He had never had use for cunning folk, but Goody Oliver had insisted. Said this woman’s tinctures cured most anything. Heard she’d conjured to find a lost child once. Peter grunted to himself. He would try her. Just the once.

From the corner of the narrow, dark room issued a tiny whimper, and

Peter looked up from the steaming pot, furrows of anxiety deepening between his eyes. He nudged one of the fire logs with a poker, loosing a crackling flutter of sparks and a gray column of fresh smoke, then drew himself up from the stool.

“Martha?” he whispered. “Ye awake?”

No further sound issued from the shadows, and Peter moved softly toward the bed where his daughter had lain for the better part of a week. He pulled aside the heavy woolen curtain that hung from the bedposts, and lowered himself onto the edge of the lumpy feather mattress, careful not to jostle it. The lapping light of the fire brushed over the woolen blankets, illuminating a wan little face framed by tangles of flax-colored hair. The eyes in the face were half open, but glassy and unseeing. Peter smoothed the hair where it lay scattered across the hard bolster. The tiny girl exhaled a faint sigh.

“Stew’s nearly done,” he said. “I’ll fetch ye some.”

As he ladled the hot food into a shallow earthenware trencher, Peter felt a flame of impotent anger rise in his chest. He gritted his teeth against the feeling, but it lingered behind his breastbone, making his breathing fast and shallow.

What knew he of ministering to the girl

, he thought.

Every tincture he tried only made her poorly.

The last word she had spoken was some three days earlier, when she had cried out in the night for Sarah.

He settled again on the side of the bed and spooned a little of the warm beans into the child’s mouth. She slurped it weakly, a thin brown stream slipping down the corner of her mouth to her chin. Peter wiped it away with his thumb, still blackened from the soot of the kitchen fire. Thinking about Sarah always made his chest tight in this way.

He gazed down at the little girl in his bed, watching closely as her eyelids closed. Since she fell ill, he had been sleeping on the wide-planked pine floor, on mildewed straw pallets. The bed was warmer, nearer the hearth, and draped in woolen hangings that had been carried all the way over from East Anglia by his father. A dark frown crossed Peter’s face. Illness, he knew, was a sign of the Lord’s ill favor.

Whatsoever happen to the girl is God’s will

, he reasoned. So to be angry at her suffering must be sinful, for that is to

be angry at God. Sarah would have urged him to pray for the salvation of Martha’s soul, that she might be redeemed. But Peter was more accustomed to putting his mind to farming problems than godly ones. Perhaps he was not as good as Sarah had been. He could not fathom what sin Martha could have committed in her five years to bring this fit upon her, and in his prayers he caught himself demanding an explanation. He did not ask for his daughter’s redemption. He just begged for her to be well.

Confronting this spectacle of his own selfishness filled Peter with anger and shame.

He worked his fingers together, watching her sleeping face.

“There are certain sins that make us devils,” the minister had said at meeting that week. Peter pinched the bridge of his nose, squinting his eyes together as he tried to remember what they were.

To be a liar or murderer, that was one. Martha had once been caught hiding a filthy kitten in the family’s cupboard, and when questioned by Sarah had claimed no knowledge of any kittens. But that could hardly be a lie the way the minister meant it.

To be a slanderer or accuser of the godly was another. To be a tempter to sin. To be an opposer of godliness. To feel envy. To be a drunkard. To be proud.

Peter gazed down on the fragile, almost transparent skin of his daughter’s cheeks. He clenched one of his hands into a tight fist, pressing its knuckles into the palm of his other hand. How could God visit such torments upon an innocent? Why had He turned away His face from him?

Perhaps it was not Martha’s soul that was in danger. Perhaps the child was being punished for Peter’s own prideful lack of faith.

As this unwelcome fear bloomed in his chest, Peter heard muddy hoofbeats approach down the lane and come to a stop outside his house. Muffled voices, a man’s and a young woman’s, exchanged words, saddle leather creaked, and then a dull splash.

That’ll be Jonas Oliver with yon woman

, thought Peter. He rose from the bedside just as a light knuckle rapped on his door.

On his stoop, draped in a hooded woolen cloak glistening from the

evening’s fog, stood a young woman with a soft, open face. She carried a small leather bag in her hands, and her face was framed by a crisp white coif that belied the miles-long journey she had had. Behind her in the shadows stood the familiar bulk of Jonas Oliver, fellow yeoman and Peter’s neighbor.

“Goodman Petford?” announced the young woman, looking quickly up into Peter’s face. He nodded. She flashed him an encouraging smile as she briskly flapped the water droplets off her cloak and pulled it over her head. She hung the cloak on a peg by the door hinge, smoothed her rumpled skirts with both hands, then hurried across the stark little room and knelt by the girl in the bed. Peter watched her for a moment, then turned to Jonas, who stood in the doorway similarly wet, blowing his nose vigorously into a handkerchief.

“Dismal night,” said Peter by way of welcome. Jonas grunted in reply. He tucked the handkerchief back up his sleeve and stamped his feet to loosen the mud from his boots, but he did not venture into the house.

“Some victual before ye go?” Peter offered, rubbing a hand absentmindedly across the back of his head. He was not sure if he wanted Jonas to accept his offer. The company would distract him, but his neighbor was even less inclined to idle chatter than he was. Sarah had always allowed that a wagon could crush Jonas Oliver’s foot and he would not so much as grimace.

“Goody Oliver’ll be waiting.” Jonas declined with a shrug. He glanced across the room to where the young woman perched, whispering to the girl in the bed. At her knees sat an attentive, disheveled-looking little dog, some dingy color between brown and tan, surrounded by muddy paw marks on the floor planking. Vaguely Jonas wondered where she might have carried the animal on their long ride; he had not noticed it, and her leather bag seemed hardly big enough.

Mangy cur

, he thought.

It must belong to little Marther.

“Come by upon the morn, then,” said Peter. Jonas nodded, touched the brim of his heavy felt hat, and withdrew into the night.

Peter settled again on the low stool near the dying hearth fire, the cooling trencher of stew on the table at his elbow. Propping his chin on his fist, he watched the strange young woman stroke his daughter’s forehead

with a white hand and heard the soft, indistinct murmur of her voice. He knew that he should feel relieved that she was there. She was widely spoken of in the village. He grasped at these thoughts, wringing what little assurance he could from them. Still, as his eyes started to blur with fatigue and worry, and his head grew heavy on his arm, the vision of his tiny daughter huddled in the bed, darkness pressing in around her, filled him with dread.

Marblehead, Massachusetts

Late April

1991

“

I

T WOULD APPEAR THAT WE ARE NEARLY OUT OF TIME,” ANNOUNCED

Manning Chilton, one glittering eye fixed on the thin pocket watch chained to his vest. He surveyed the other four faces that ringed the conference table. “But we are not quite done with you yet, Miss Goodwin.”

Whenever Chilton felt especially pleased with himself his voice became ironic, bantering: an incongruous affectation that grated on his graduate students. Connie picked up on the shift in his voice immediately, and she knew then that her qualifying examination was finally drawing to a close. A sour hint of nausea bubbled up in the back of her throat, and she swallowed. The other professors on the panel smiled back at Chilton.

Through her anxiety, Connie Goodwin felt a flutter of satisfaction tingle somewhere in her chest, and she permitted herself to bask in the sensation for a moment. If she had to guess, she would have said that the exam was going adequately. But only just. A nervous smile fought to break across

her face, but she quickly smothered it under the smooth, neutral expression of detached competence that she knew was more appropriate for a young woman in her position. This expression did not come naturally to her, and the resulting effort rather comically resembled someone who had just bitten into a persimmon.

There was still one more question coming. One more chance to be ruined. Connie shifted in her seat. In the months leading up to the qualifying exam, her weight had dropped, slowly at first, and then precipitously. Now her bones lacked cushioning against the chair, and her Fair Isle sweater hung loosely on her shoulders. Her cheeks, usually flush and pink, formed hollows under her sloping cheekbones, making her pale blue eyes appear larger in her face, framed by soft, short brown lashes. Dark brown brows swept down over her eyes, screwed together in thought. The smooth planes of her cheeks and high forehead were an icy white, dotted by the shadowy hint of freckles, and offset by a sharp chin and well-made, if rather prominent, nose. Her lips, thin and pale pink, grew paler as she pressed them together. One hand crept up to finger the tail end of a long, bark-colored braid that draped over her shoulder, but she caught herself and returned the hand to her lap.

“I can’t believe how

calm

you are,” her thesis student, a lanky young undergraduate whose junior paper Connie was advising, had exclaimed over lunch earlier that afternoon. “How can you even eat! If I were about to sit for my orals I would probably be nauseous.”

“Thomas, you get nauseous over our tutorial meetings,” Connie had reminded him gently, though it was true that her appetite had almost vanished. If pressed, she would have admitted that she enjoyed intimidating Thomas a little. Connie justified this minor cruelty on the grounds that an intimidated thesis student would be more likely to meet the deadlines that she set for him, might put more effort into his work. But if she were honest, she might acknowledge a less honorable motive. His eyes shone upon her in trepidation, and she felt bolstered by his regard.

“Besides, it’s not as big a deal as people make it out to be. You just have

to be prepared to answer any question on any of the four hundred books you’ve read so far in graduate school. And if you get it wrong, they kick you out,” she said. He fixed her with a look of barely contained awe while she stirred the salad around her plate with the tines of her fork. She smiled at him. Part of learning to be a professor was learning to behave in a professorial way. Thomas could not be permitted to see how afraid she was.

The oral qualifying exam is usually a turning point—a moment when the professoriate welcomes you as a colleague rather than as an apprentice. More infamously, the exam can also be the scene of spectacular intellectual carnage, as the unprepared student—conscious but powerless—witnesses her own professional vivisection. Either way, she will be forced to face her inadequacies. Connie was a careful, precise young woman, not given to leaving anything to chance. As she pushed the half-eaten salad across the table away from the worshipful Thomas, she told herself that she was as prepared as it was possible to be. In her mind ranged whole shelvesful of books, annotated and bookmarked, and as she set aside her luncheon fork she roamed through the shelves of her acquired knowledge, quizzing herself. Where are the economics books? Here. And the books on costume and material culture? One shelf over, on the left.

A shadow of doubt crossed her face. But what if she was not prepared enough? The first wave of nausea contorted her stomach, and her face grew paler. Every year, it happened to someone. For years she had heard the whispers about students who had cracked, run sobbing from the examination room, their academic careers over before they had even begun. There were really only two ways that this could go. Her performance today could, in theory, raise her significantly in departmental regard. Today, if she handled herself correctly, she would be one step closer to becoming a professor.

Or she would look in the shelves in her mind and find them empty. All the history books would be gone, replaced only with a lone binder full of the plots of late-1970s television programs and rock lyrics. She would open her mouth, and nothing would come out. And then she would pack her bags to go home.

Now, four hours after her lunch with Thomas, she sat on one side of a polished mahogany conference table in a dark, intimate corner of the Harvard University history building, having already endured three solid hours of questioning from a panel of four professors. She was tired but had a heightened awareness from adrenaline. Connie recalled feeling the same strange blending of exhaustion and intellectual intensity when she pulled an all-nighter to polish off the last chapter of her senior thesis in college. All her sensations felt ratcheted up, intrusive, and distracting—the scratch of the masking tape with which she had provisionally hemmed her wool skirt, the gummy taste in her mouth of sugared coffee. Her attention took in all of these details, and then set them aside. Only the fear remained, unwilling to be put away. She settled her eyes on Chilton, waiting.

The modest room in which she sat featured little more than the pitted conference table and chairs facing a blackboard stained pale gray with the ghostly scrawls of decades of chalk. Behind her hung a forgotten portrait of a white-whiskered old man, blackened by time and inattention. At the end of the room a grimy window stood shuttered against the late afternoon sunlight. Motes of dust hung almost motionless in the lone sunbeam that lighted the room, illuminating the committee’s faces from nose to chin. Outside she heard young voices, undergraduates, hail one another and disappear, laughing.

“Miss Goodwin,” Chilton said, “we have one final question for you this afternoon.” Her advisor leaned into the empty center of the table, sunlight moving over his silver hair, stirring the dust into a glittering corona around his head. On the table before him, his fingers sat knotted as carefully as the club tie at his throat. “Would you please provide the committee with a succinct and considered history of witchcraft in North America?”

T

HE HISTORIAN OF

A

MERICAN COLONIAL LIFE, AS

C

ONNIE WAS, MUST BE

able to illustrate long-dead social, religious, and economic systems down to the slightest detail. In preparation for this exam, she had memorized, among

other things, methods for preparing salt pork, the fertilizer uses of bat guano, and the trade relationship between molasses and rum. Her roommate, Liz Dowers, a tall, bespectacled student of medieval Latin, blond and slender, one evening had come upon her studying the Bible verses that commonly appeared in eighteenth-century needlepoint samplers. “We have finally specialized beyond our ability to understand each other,” Liz had remarked, shaking her head.

For a last question, Connie knew Chilton had really given her a gift. Some of the earlier ones were considerably more arcane, even beyond what she had been led to expect. Describe the production, if she would, of the different major exports of the British colonies in the 1840s, from the Caribbean to Ireland. Did she think that history was more a story of great men acting in extraordinary circumstances, or of large populations of people constrained by economic systems? What role, would she say, did codfish play in the growth of New England trade and society? As her gaze roamed around the conference table to each professor’s face in turn, she saw mirrored in their watching eyes the special area of expertise in which each had made his or her name.

Connie’s advisor, Professor Manning Chilton, looked at her across the table, a small smile flickering at the edge of his mouth. His face, framed with a fringe of brushed cotton hair, was seamed at the forehead, creased by folds from the corners of his nose to his jaw, which the low sunlight in the conference room cast in deep shadow. He carried himself with the easy assurance of the vanishing breed of academic who has spent his entire career under Harvard’s crimson umbrella, and whose specialization in the history of science in the colonial period was fueled by a childhood spent shooed away from the drawing room of a stately Back Bay town house. He bore the distinguished smell of old leather and pipe tobacco, masculine but not yet grandfatherly.

Chilton was flanked around the conference table by three other respected American historians. To his left perched Professor Larry Smith, a tight-lipped, tweedy junior faculty economist, who asked knotty questions

designed to indicate to the senior professors his authority and expertise. Connie glowered at him; twice already in the exam he had asked questions probing where he knew her knowledge was scanty. She supposed that that was his job, but he was the only committee member likely to recall his own qualifying exams. Perhaps she had been naïve to expect solidarity from him; oftentimes professors of his rank were the hardest on grad students, as if to make up for the indignities they felt themselves to have suffered. He smiled back at her primly.

To Chilton’s right, her chin on one jeweled hand, sat Professor Janine Silva, a blowsy, recently tenured gender studies specialist who favored topics in feminist theory. Her hair was wilder and wavier today than usual, with a burgundy sheen that was patently false. Connie enjoyed Janine’s willful denial of the Harvard aesthetic; long floral scarves were her trademark. One of Janine’s favorite rants concerned Harvard’s relative hostility to women academics; her interest in Connie’s career sometimes bordered on the motherly, and as a result Connie consciously had to work to control the pseudo-parental transference that many students develop toward their mentors. While Chilton held more power over her career, Connie dreaded disappointing Janine the most. As if sensing this momentary flicker of anxiety, Janine sent Connie a thumbs-up, partly concealed behind one of her arms.

Finally, to Janine’s right hunched Professor Harold Beaumont, Civil War historian and staunch conservative, known for his occasional grumpy forays onto the Op-Ed page of the

New York Times

. Connie had never worked closely with him and had placed him on her committee only because she suspected that he would have very little personally invested in her performance. Between Janine and Chilton she thought she had enough expectations to manage. As these thoughts traveled through her mind, she felt Beaumont’s dark eyes burning a tight round hole in the shoulder of her sweater.

Connie gazed down at the surface of the table and traced the outline of the initials that had been carved there, darkened by decades of waxy polish. She roamed through the file cabinets in her brain, looking for the answer

that they wanted. Where was it? She knew it was there somewhere. Was it under

W

, for “Witchcraft”? No. Or was it listed under

G

, for “Gender Issues”? She opened each mental drawer in turn, pulling out index cards by the handful, shuffling through them, and then tossing them aside. The bubble of nausea rose again in her throat. The card was gone. She could not find it. Those whispered stories about students failing, they were going to be about

her.

She had been given the simplest question possible, and she could not produce an answer.

She was going to fail.

A haze of panic began to cloud her vision, and Connie fought to keep her breath steady. The facts were there, she must just focus enough to see them. Facts would never abandon her. She repeated the word to herself—

facts

. But wait—she had not looked under

F

, for “Folk Religion, Colonial Era.” She pulled the mental drawer open, and there it was! The haze cleared. Connie straightened herself against the hard chair and smiled.

“Of course,” Connie began, shoving her anxiety aside. “The temptation is to begin a discussion of witchcraft in New England with the Salem panic of 1692, in which nineteen townspeople were executed by hanging. But the careful historian will recognize that panic as an anomaly, and will instead want to consider the relatively mainstream position of witchcraft in colonial society at the beginning of the seventeenth century.” Connie watched the four faces nodding around the table, planning the structure of her answer according to their responses.

“Most cases of witchcraft occurred sporadically,” she continued. “The average witch was a middle-aged woman who was isolated in the community, either economically or through lack of family, and so was lacking in social and political power. Interestingly, research into the kinds of

maleficium

”—her tongue tangled on the Latin word, sending it out with one or two extra syllables, and she cursed inwardly for giving in to pretension—“which witches were usually accused of reveals how narrow the colonial world really was for average people. Whereas the modern person might assume that someone who could control nature, or stop time, or tell the future, would

naturally use those powers for large-scale, dramatic change, colonial witches were usually blamed for more mundane catastrophes, like making cows sick, or milk go sour, or for the loss of personal property. This microcosmic sphere of influence makes more sense in the context of early colonial religion, in which individuals were held to be completely powerless in the face of God’s omnipotence.” Connie paused for breath. She yearned to stretch but restrained herself. Not yet.