The Pigman (7 page)

Authors: Paul Zindel

“No, Mom.”

She looked me over carefully, checking for any clues as to what mood I left Bore in.

“Your father’s a little tired tonight. Maybe you’d better go over to a friend’s house to do your homework? I mean he’s worked hard, and I don’t think we should aggravate him, do you?”

“No, Mom.”

“Would you like a glass of wine?” Mr. Pignati offered, straightening up a few things in the living room. It was great how happy he was to see us. I can’t remember Bore, or my mother either for that matter, ever looking happy to see me, let alone when I came into the house with

a friend.

“That would be pleasant,” Lorraine said.

“This is a great house you’ve got,” I said. “It’s well… interesting.”

He beamed.

“Come on, and I’ll show you around,” he said, smiling to beat the band.

He took us through the downstairs part, and the less you know about that the better. The first time we were there we saw the hallway when we came in and the stairs that went to the upper floor—and the living room that was really lived in. There was also this dining room affair with the kind of furniture you see everybody put out on the street for the Sanitation Department in the spring.

Then on the other side there was a door leading to a porchlike room that looked like someone had tried to fix it up so it could be lived in but had failed. And the only other thing on the first floor was a kitchen, and that’s where we stopped because Lorraine was hungry. I mean, we were really making ourselves at home there after awhile. At first we had just stood around, bashful about touching his things. We’d walk over to a bookcase and touch a book and stroll by a table and admire the handle on a drawer. But in fifteen minutes we were laughing with the Pigman like it was a treasure hunt, and he kept smiling and saying, “Just make yourself at home. You just go right ahead and make yourself at home.” But it was really all a lot of junk. The most interesting thing I found was a table drawer full of old

Popular Mechanics

magazine, and the most interesting thing Lorraine found was the icebox.

“Try some of this,” Mr. Pignati insisted, holding up a bowl of little roundish things that looked as if they were in a spaghetti sauce.

“Ummmm!”

Lorraine muttered as she stuffed a few into her mouth. “What are they?”

“Scungilli,” the Pigman said. “They’re like snails.”

“May I use your bathroom?” Lorraine asked her face turning stark white.

“Right upstairs.”

Mr. Pignati and I went into the room with all the pigs, and I started lifting the bigger ones to see what country they were made in.

You could hear Lorraine upstairs for about five minutes. When she came downstairs, she had this picture in her hands.

“Who’s this?”

There was a pause. Then the smile faded off the Pigman’s face. He took the picture from her and moved over to the stuffed armchair and sat down.

“My wife Conchetta,” he said, “in her confirmation dress.”

“Conchetta?” Lorraine repeated nervously. We both knew something was wrong but couldn’t put our finger on it. I got the idea that maybe his wife had run off to California and left him. I mean, you couldn’t blame her when you stop to think that her husband’s idea of a big time was to go to the zoo and feed a baboon.

“She liked that picture because of the dress,” he went on. “It was the only picture she ever liked of herself.”

He got up and put it in the table drawer where all those old

Popular Mechanics

books were, and when he turned around, his eyes looked like he was going to start crying. Suddenly he forced a smile and said, “Go upstairs and look around while I get you some wine. Please feel at home, please….”

Then he went down the hall toward the kitchen.

“What else is up there?” I whispered to Lorraine.

“I don’t know.”

I decided to take a look, but frankly there wasn’t much to look at. At the top of the stairs was this plain old bathroom with a shower curtain that had all kinds of fish designs on it.

When I opened the door on the left, I got a little bit scared because there was one of those adjustable desk lamps with a long neck that made it look like a bird about to attack. I put the light on though, and the room was a huge bore. The ceiling slanted on the far side, and there was only one window. It was okay if you wanted to keep somebody as the Prisoner of Zenda, but it looked like a rotten place to work. All it had was this big desk made by taking a thick piece of plywood and laying it over two wooden horses, and a bookcase with blueprints and stuff in it, and a big oscilloscope, with its guts hanging out, in the corner. There were three old TV sets too, but they looked like they didn’t even work.

Then I went into the room on the right of the hall. It was a bedroom—much neater than the rest of the house—and it had a lot of drawers and things to go through.

The bedroom had a closet too, so I started with that. There were all kinds of dresses in it, and lacy ladies’ coats, and hats that looked like they must have been the purple rage at the turn of the tenth century. It was a big loss; it really was. And let me tell you, this room was a little nerve-racking too. It had a double bed with a cover made of millions of ruffles, and the way the pillows were laid out, it looked like there might be a dead body underneath. I checked that out right away, but there were only pillows. Then I found one drawer in the dresser bureau that had a lot of papers in it.

There were some pictures, and I looked at them quickly. Also there were some bills and old letters and things tied up with a putrid ribbon and then—sort of funny—this little pamphlet caught my eye. It was called

WHAT EVERY FAMILY SHOULD KNOW.

That’s all there was on the cover, and it really had my curiosity up, so I opened it. The very first page gave me the creeps.

I ditched that quick enough, but one thought struck me about that dumb high school I go to. They think they’re so smart giving the kids garbage like

Johnny Tremain

and

Giants in the Earth

and

Macbeth

, but do you know, I don’t think there’s a single kid in that whole joint who would know what to do if somebody dropped dead.

In the same drawer there was a leather case with a broken thingamajig to close it, and it had jewelry in it—a lot of junky women’s jewelry that looked like it was made out of paste and stuff. I mean, that wife of his—Mr. Pignati’s wife—looked like she didn’t take anything with her to California. All those clothes in the closet. But how was I supposed to know? Maybe she went to visit the Pigman’s sister in a nudist camp or something. They do anything in California—crazy religions and that kind of thing.

What should be done first?

Who is our Funeral Director?

Do we have a cemetery preference?

Are there any organizations or friends to invite?

What kind and type of casket?

Do we have money for the expense?

If so, where? How much?

If not, where is the money to come from:

Veterans’ benefits?

Social Security?

Insurance?

These, and many more, are the questions that are asked when the time comes. Peace of mind will be yours if you follow this booklet.

If you need more than one book, just call the Silver Lake Company, and we will forward it at once.

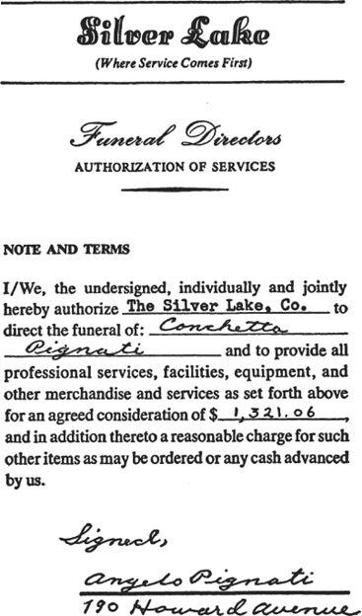

Then I found this bill right in with all the jewelry and junk and her Social Security card, and that’s when I knew Conchetta Pignati was not in California. I knew that where Conchetta Pignati was she was never coming back.

H

is wife’s

dead

!” John whispered.

“What?”

“I just found her funeral bill.”

A terrible chill ran through me when he said that, because I had been afraid Conchetta was not away on a vacation. I didn’t exactly suspect Mr. Pignati of having murdered her and sealed her body behind a wall in the cellar, but I was suspicious. There was something about the glaze in his eyes when he laughed that disturbed me because I could tell he didn’t really believe his own laughter. It was a nervous type of laughing, the same kind as that of a landlady we once had after her husband died in a dentist’s chair while he was under gas.

“Did you see the ad in yesterday’s paper?” Mr. Pignati asked, finally coming back with more of the red wine.

“No.”

“For sale: Complete set of encyclopedias, never used. Wife knows everything.” And then he let out that laugh again.

I just couldn’t smile at his joke. I thought it was very sad. I mean, that cute little girl in the ruffled dress had already grown up, gotten married, lived her life, and was underground somewhere. And Mr. Pignati wasn’t able to admit it. That landlady used to think her husband was going to come back one day too, but she died less than two months after him. I’ve always wondered about those cases where a man and wife die within a short time of each other. Sometimes it’s only days. It makes me think that the love between a man and a woman must be the strongest thing in the world.

But then look at my father and mother, although maybe they didn’t ever really love each other. Maybe that’s why she got the way she is.

“I found this upstairs.” John smiled, holding a small plastic card. “What is it?”

The Pigman explained what a charge card was.

“You mean you just sign your name, and a department store lets you take whatever you want, and you don’t have to pay for it for months?” John asked, wide-eyed.

Mr. Pignati said he only got the card so his wife could go shopping in the fancy-food delicatessen they’ve got at Beekman’s.

“She loves delicacies,” he said.

And I remembered the taste of the scungilli.

When I got home that night, I thought of them again, but another thought struck me. I realized how many things the Pigman and his wife must have shared—even the fun of preparing food. Good food is supposed to produce good conversation, I’ve heard. I guess it’s no wonder my mother and I never had an interesting conversation when all we eat is canned soup, chop suey, and instant coffee. I think I would have learned how to cook if she had ever encouraged me, but the one time I tried baking a cake she said it tasted horrible and was a waste of money.

“Did you fix my coffee?”

“Yes.”

“This one has sex on the brain. He has only got a couple of months to live, and he’s still got itchy fingers.” I watched my mother powdering her nose at the kitchen table. She leaned forward between sips of coffee, dabbing at her face.

“The last nurse quit because she couldn’t control his hands. He’s always trying to touch something, but I put a stop to that the first time he tried anything.”

“Can I make you some eggs?”

“Don’t bother. I’ll have breakfast at their house. His wife is treating me with kid gloves because they know a nurse isn’t easy to come by—particularly when they’ve got to put up with what I’ve got to. Make yourself something.”

“I’m not hungry.”

“Make sure you scrub the kitchen floor today. In fact I’d concentrate on the kitchen. It’s worse than anything else.”

“We’re out of cleanser. Shall I buy a can?”

“Wait until I see if I can take one from the job. I think I saw some when I was going through the closets yesterday.” She checked herself in the bathroom mirror and then headed for the door. “Give me a kiss—and lock the doors and windows. Don’t open for anyone, do you hear me?”

“Yes, Mother.”

“If a salesman rings the bell, don’t answer it.”

I watched her waiting on the corner until the bus came. If I strained my neck, I could always catch a glimpse of her standing there in her white uniform and white shoes—and she usually wore a short navy-blue jacket, which looked sort of strange over all that white. As I watched her I remembered all the times she said how hard it was to be a nurse—how bad it was for the legs, how painful the varicose veins were that nurses always got from being on their feet so much. I could see her standing under the street light… just standing there until the bus came. It was easy to feel sorry for her, to see how awful her life was—even to understand a little why she picked on me so. It hadn’t always been like that though.