The Pirate Queen (19 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

W

HEN

I dream about my motherâwhen I allow myself to remember those dreamsâI dream, not so much that she is dead, but that she's across the water. She's on a ferry that is just departing (there's still time to step aboard); she is on a raft in the river, a raft that has just gone downstream ahead of me. Or

I dream that she's swimming or flying, somehow moving around me, a liquid shifting presence, not close, but near. She doesn't always look like herself, but I know her in my body, in every molecule.

Sometimes she calls to me. She wants me to follow. But I don't follow. What would happen if I went toward her?

Once, during a dream in which she was leaving on a big car ferry, I knew I had to get hold of her. I ran to a phone booth on the dock, frantic with anxiety, and flipped through the phone book. I paged and paged but I couldn't find Wilson, nor could I recall the street where our family lived. It was night in this dream, and there were hot white beams spotlighting the ferry. I heard engines roar, the water churn hugely as the ferry pushed away from the dock. I stood there in the lit phone booth and I knew she had a different name now than what I remembered, and a different address, too.

It has been dreams of parting that have haunted me, not dreams of drowning. I was quite a young child when I had my first dream of drowning. How well I recall the first moment of panic, followed by the knowledge that here, underwater, I could breathe.

Now, on the

St. Sunniva,

I fell asleep to the seesaw of the ship, and I had a dream, darker in color than the light aqua nightmares of childhood, of falling off the ship and down through the ocean. I would have many drowning dreams on this trip. This was the first, but all it was, was falling. I fell a long time and it was cold and leaden.

W

HEN

I awoke it was dim in my cabin; outside, through the porthole, spattered with rain, I saw misty cliffs and raw, rocky

shores. This must be the Shetland Islands, I thought, and was afraid for a moment. How dark everything looked out there, how gray and wet and inhospitable. I'd read that in olden times the Shetlanders would not rescue a drowning person, even when it was safe and easy. For they believed that the sea demanded a sacrifice. If you took away the sea's victim, someone else, perhaps you yourself, would be taken instead.

I curled back into sleep, held to the beating heart of the ship and rocked by the waves. Now I was enveloped and safe and warm in my berth, in my cabin. When I next woke up, the

St. Sunniva

was docking in Lerwick. The magic eggshell had broken, with earth at the bottom and sky at the top. Sun shone into the space between. The thick gray mist was lifting and for an instant Shetland, green and bright, looked like Hilda-land. I rushed to pack my things and disembark.

THE LONELY VOYAGE OF BETTY MOUAT

Sumburgh Head, the Shetland Islands

I

T WAS

a bitter cold day at the end of January 1886, when Betty Mouat took passage on a ship bound for Lerwick. Some might wonder why Betty didn't just walk the twenty-four miles from her home at the southernmost tip of the Shetland Islands to the capitol. Walking was common at a time when the roads were bad and few had money for horse travel. It was winter, after all, and the seas were notoriously rough. But Betty Mouat didn't walk. She'd been born with one leg shorter than the other. She was also, by the standards of the day, old and rather frail. She was fifty-nine.

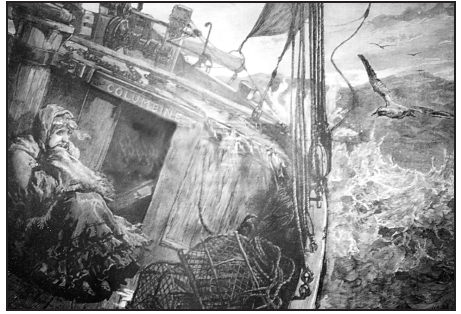

Betty Mouat had traveled to Lerwick by ship many times before, carrying shawls and other knitting to sell in town. The morning she embarked on the

Columbine,

she had a bundle of forty shawls, as well as a bottle of milk and two halfpenny biscuits for sustenance on the journey. The voyage was expected to last two or three hours, and Betty was the only passenger.

Eight days later the

Columbine

smashed into the Norwegian coast, three hundred miles to the northeast. Betty was still the only passenger; she was also the only person on the ship.

I

N ORDER

to find the house where Betty Mouat had lived, I'd come by bus from Lerwick down to Sumburgh Head, a journey that now takes about half an hour. Sumburgh is the longer of two pincher-shaped peninsulas that seem to reach out after Fair Isle, which can just be seen on the horizon. Sumburgh is the site of the Bronze and Iron Age ruins of Jarlshof and the Victorian hotel that was once the home of the Laird of Sumburgh. In Betty's day the land was inhabited by crofters, tenants of the laird, who fished and farmed in a limited way. Now much of it is home to Shetland's main airport. Betty lived with her half-brother and his family in a small stone house on the shorter of the two pinchers, known as Scatness.

One of the many things I liked about Shetland was the place names: Spiggie, Bigton, Brig o' Waas, Busta, Symbister, Quarff, Mid Yell, Gloup, Funzie, Muckle Flugga. Fitful Head was another. You could see the massive headland of Fitful Head from Sumburgh. It was the fictional home of Norna, the prophetess in Sir Walter Scott's novel

The Pirate,

and as I looked at its bulky

outline across the bay, I could almost hear Norna's runic incantations and her weird cry, “Do not provoke Norna of Fitful-head!” Many of the Shetland place names are of Norse origin as, from sometime in the ninth century, Shetland had been a Norwegian province. Only in 1469 were the islands forfeited to Scotland in lieu of an unpaid royal dowry.

I had lunch at the Sumburgh Hotel and strolled through dunes covered in marram grass to a glittering white beach. The sky was a very pale blue and the clouds moved fast, in long wispy streamers, as if they were being sucked in the direction of Fair Isle twenty-five miles to the south. Behind me, to the north, thunderclouds were stacked like giant bundles of indigo and black velvet with gold piping. Earlier, in Lerwick this morning, it had been raining; now, on the beach, between Sumburgh and Scatness, the light was clear, almost silvery. From time to time there was the sound of a small jet landing or departing, and then silence, punctuated by the cries of oystercatchers and gulls. I had my bird book with me and was trying to identify the gulls. I thought a black-backed gull sounded like a dog snarfling in a dream. The bird book called it an angry

kuk-kuk-kuk.

The common gull was meant to have a more “benign” expression than the herring gull, but so far I had only distinguished them by the color of their legs: yellow and pink.

East was a blue sky; west was trouble. You often saw the two weather systems collide over Shetland; it was what made the weather change so swiftly here. Situated over one hundred miles out into the Atlantic, the islands had been shaped by wind and waves into a landscape of dramatic bluffs and barren ridges. Except for a few pockets of stunted trees in Lerwick, and some battered shrubbery and flowers around individual houses, much of the vegetation was grasses and wildflowers. I'd noticed earlier,

in Orkney, which was a traditionally agricultural land, there was a great deal of talk, mainly moaning and complaining, about the wet spring and the slow start of summer. But in Shetland the weather as a topic hardly came up at all. The constant massing and dispersing of the clouds, the restless coming and going of the sunshine and the rain were quite normal here.

W

HEN

B

ETTY

Mouat set off in the

Columbine,

the day was cold and clear, but the wind came up offshore and the sea quickly grew heavy. The skipper, James Jamieson, and his two crewmen, regularly sailed up and down the Shetland coast, but that day luck wasn't with him. In resetting the sail for the stronger wind, he and his first mate were swept off the ship. The mate managed to claw his way back onboard, but to his great distress he saw Captain Jamieson, of whom he was very fond, still flailing in the sea. The mate and the other crewman immediately launched a boat to save the captain, but they were too late. The captain's head had disappeared. Worse, when they turned back to the

Columbine,

they found that the ship had already tacked off to the northeast. It was all they could do to get themselves through heavy surf to shore.

When the voyage began, Betty Mouat had settled herself below deck with her quart bottle of milk and two biscuits. The ship soon began to roll so much that when she heard shouting, she wasn't able to climb up to the open hatchway to take a look. She heard “Get away the boat,” and then nothing except the wind. When she finally managed to get up the stairs, she found the boom swinging wildly in the gale, the mainsail flapping, and all three crewmen gone. Waves were breaking over the bow; the sky had darkened; a terrible storm was taking shape around her.

B

Y THE

time I went looking for Betty Mouat's croft house in Scatness, I'd been in Shetland about a week, asking my usual questions about women and the sea. My bed-and-breakfast host in Lerwick, Mr. Gifford, first told me about two girls from an island in the north of Shetland who drifted to Norway in a boat. Later I read about these two servant girls from the small island of Uyea, south of Unst, who had rowed over to the even smaller islet of Haaf Gruney to milk cows kept there for grazing. On the return trip they ran into a gale and were carried across the sea to the Norwegian coast. It's said they married Norwegians. At any rate they never returned. A surprising number of girls were blown over the northern seas, as it turned out. Some were from England, a couple from Holland, the majority from Scotland. Although some were blown south, more drifted to the Norwegian coast, the result, no doubt, of the Gulf Stream's north-flowing current.

It was of interest to me that almost all the men I asked in Shetland about women and the sea immediately began to tell me the story of Betty Mouat and the other women and girls who drifted to Norway in boats. The greatest drifter of them all, of course, was St. Sunniva, whose name now adorns the ship that brought me to Lerwick. St. Sunniva was a tenth-century Christian princess from Ireland who, in escaping from her Viking persecutors, jumped into a ship with her companions and pushed off without benefit of oars, rudders, or sails, because she trusted in God to save them. Although St. Sunniva bypassed Shetland to land in Norway, the remains of a chapel once dedicated to her can be found on the small isle of Balta off Unst.

No one knows how long it took St. Sunniva to reach Norway, but it took Betty Mouat and the

Columbine

more than a week. For all that time she had no idea where she was and no way of ascertaining. The storm battered the ship for four days before there was a respite and some sun, and then another storm blew up. Betty Mouat had nothing to eat but her milk and biscuits; she spent most of her time holding on to a rope and bracing herself against the rolling of the ship. Only at the end did she see land and shortly afterward feel the shock of the

Columbine

going aground. By some miracle the

Columbine

had missed the reefs off an island north of Ã

lesund and had lodged itself firmly on the rocks. Betty climbed on deck and found two boys on shore staring at her. They shouted to each other in their own language, and then the boys ran off for help. Fishermen not far away had been watching the lurching of the boat and its crash into the rocks; they were astonished to find an elderly woman onboard, alone.