The Pirate Queen (26 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

The sun was still high at this northern latitude. It was not a blaze of sun; it diffused through the sea mists as if silver and gold were being gently churned from the waterfalls and sprayed into the air. The combination of colors was electrifying: the jade

green hills, the silvery gold light, the black houses with green grass roofs. There were no sounds but the round roll of the surf on the shore and the squashed-ducky cries of the oyster catchers. Back in Gudrún's day there would almost always have been ships and longboats out to sea; I strained my eyes to see one on the horizon. I imagined her standing on the shore, waiting day after day for her husband to return. Then, I had another vision, a woman rowing.

All over Tórshavn hung posters for a film called

Barbara

that showed a woman pulling the oars of a small boat in the direction of a merchantman sailing off into the fog. The film came from a classic Faroese novel about a captivating heroine who enchanted, then betrayed, a pastor sent from Copenhagen. The novel, in turn, was based on the real story of a woman called Beinta, who'd had a habit of marrying clergymen in the eighteenth century. Although the poster was misleadingâBarbara/Beinta was not a seafarerâthere had been a famous Barbara in Faroese myth, a sea sorceress.

The southernmost island of Suduroy was where this mythical Barbara of Sumba had lived. She'd been tried as a witch, but the judge dismissed the case on the grounds that she was too beautiful to be tarred. According to legend she once had a contest with the sorcerer Guttorm to see whose spells were stronger. Barbara raised such a storm while Guttorm and his sons were at sea that the waves turned blood red. When Guttorm reached shore, he found Barbara sitting on a hillside by a stream, her long yellow hair loose on her shoulders. Guttorm cut off her hair, and thus vanquished much of her power. He bound her to a chair, put it on the roof, and called up a storm from the northeast. When she was finally let go the next day, her spirit was broken. That's pretty much the message of the novel

and film, too, though the film is more ambiguous about Barbara's punishment. She's allowed to row off endlessly into the sea after her lover instead of returning, humiliated, to Tórshavn.

I had to admit that it was a fine thing to walk around Tórshavn and see my name emblazoned everywhere. Barbara as a name had fallen out of favor in the United States, as dated now as Gertrude or Hazel of my mother's generation. Barbaras have been around all century, but the bulk of them were conceived in the forties and fifties. In the United States I've noticed that people rarely call me by my full name; it's too much of a mouthful. They want to call me Barb. Some of my friends call me just B. In Spain my name sounds lovely, with the

r

's rolling through it like thunderâno accident that St. Barbara is the patron saint of artillery. My younger brother, of course, always pointed out that one of the meanings of my name is

stranger. Foreigner

is how I prefer to think of it, not

barbarian.

I stood on the shore in this lonely place, thinking about the Barbaras of old, and about Hanus undir Leitinum. I was thinking about names and naming, about being so firmly attached to a place that you took its name, that you were of it. Two of my grandparents, immigrants from Ireland and Sweden, came from a peasantry that was once part of the land, and they put down roots in the Midwest. But my parents moved west for new opportunities, and my brother and I never considered staying in Long Beach. I was more rooted in the Pacific Northwest than I'd ever been in Southern California.

Yet if I could take the name of my family home, I would choose one of the wonderful street names that some fanciful developer had given to my childhood neighborhood: Monlaco, Gondar, Faust, Senasac.

Barbara of Gondar, that had a nice ring.

F

IVE HUNDRED

years before Gudrún sent her ships far and wide from HúsavÃk, another powerful woman traveled through the Faroes and stayed some time before sailing on to Iceland. Her name was Audur djúpúdga, Aud the Deep-Minded. Her father was Ketil Flat-Nose; one of her sisters was called Jorunn Wisdom-Slope. Aud's story is told in the two primary sources of Icelandic history, Ari the Wise's twelfth-century

Book of the Icelanders

and the

Book of Settlements,

compiled during the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, where she's remembered as one of the four most important settlers in the new country.

We also know of Aud from the

Laxdæla Saga,

where she's called Unn. According to the saga, Ketil Flat-Nose was a powerful lord in Norway, who decided to leave the country, like many well-born provincial chieftains, rather than submit to King Harald Fine-Hair, who was trying to unite Norway by destroying other seats of power. Ketil's two sons, Bjorn and Helgi, set off for Iceland to make their fortunes, while Ketil took the rest of his kinsmen and women to Scotland. Aud married Olaf the White, a Norse-Irish king. He was killed in battle, as was her son, Thorstein the Red. An early chapter in the

Laxdæla Saga

describes her decision to abandon Scotland and join her brothers in Iceland:

When she learned that her son had been killed she realized that she had no further prospects there, now that her father, too, was dead. So she had a ship built secretly in a forest, and when it was completed she loaded it with valuables and prepared it for a voyage. She took with her all her surviving kinsfolk; and it is generally thought that it would be hard to

find another example of a woman escaping from such hazards with so much wealth and such a large retinue. From this it can be seen what a paragon amongst women she was.

The ship constructed for Aud's voyage to Orkney and the Faroes and her transatlantic voyage to Iceland was a

knarr

or

hafskip

âan ocean ship. These were seagoing trading vessels, smaller versions of the

langskips,

the great sailing galleys with which the Vikings harried and plundered Europe from the eighth century to the twelfth. These trading vessels were clinker-built and broader in the beam than longships; they were usually about fifty feet long, and had a curved prow, without the dragon head of the fighting longships. They carried one large square sail of hide or thickly woven cloth, and were steered by a side rudder. The tackle and anchor were made of walrus hide. The cargo was stored in an open hold and covered with ox hides. There were few oars, as the ocean ship wasn't made for battle; it was a load-bearing sailing vessel, capable of carrying from forty to fifty people, as well as livestock and supplies. Each voyager had something called a

hudvat,

a hammock in which they carried their possessions and which offered shelter when emptied. No fires could be set at sea; those onboard ate dried fish and meat and drank sour milk and beer. It was with this ship that the Norse people colonized Iceland, one of the largest planned migrations of medieval times.

I

STOOD

on the deck of the

Norröna

as we sailed out of Tórshavn's harbor on a bright evening. There were dark maroon clouds to the north, but from deck the town looked charming with its grassy-roofed houses of red, black, and blue. I wasn't sorry to be leaving; I was eager to move on to Iceland, a crossing of about fifteen hours. The

Norröna

was carrying a by-now thoroughly weary assembly of a thousand or so passengers, a number of whom had started their voyage in Denmark days ago. The ship was powered by huge engines and navigated using GPS and computers. There is always romance in crossing the sea; no matter how large the ship, it is always so very much smaller than the ocean. Yet for most of the voyage passengers are encouraged to turn their minds to other things than looking at the horizon and contemplating the vastness of the deep. The

Norröna

lacked the amenities of a first-class cruise ship, but it had a bar and a video parlor, both of which were heavily in use.

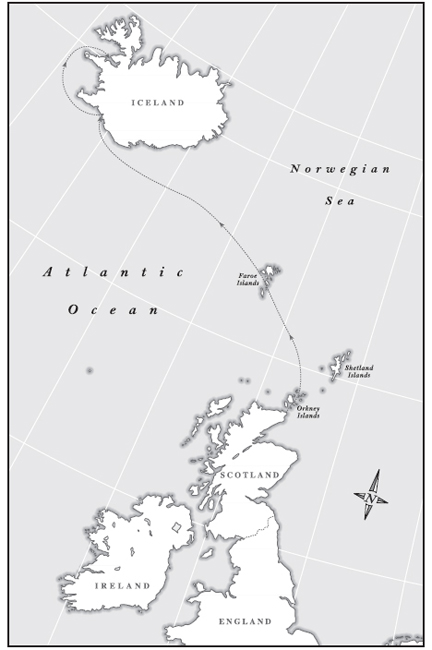

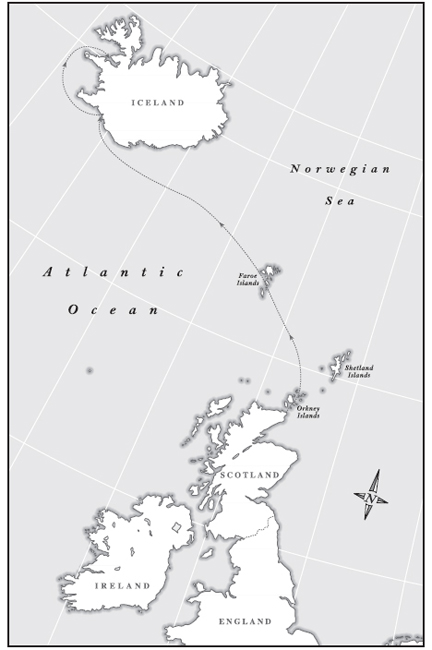

The journey of Aud the Deep-Minded

I'd already investigated my cabin and found it lacked a certain mystery with another person occupying the bottom bunk. She was Norwegian. She said she'd been on the ship from Bergen, or about twenty-five hours by now, and just wanted it to be over. The cabin smelled of her toiletries and some packaged fish cakes that she must have brought from Norway.

The wind grew stronger as we sailed north alongside and through the Faroes, and the rain began to spill like shards of stained glass from the gilt-lined maroon and indigo storm clouds. For a while the view was glorious, and the dedicated photographers were on hand with expensive equipment to capture the dramatic chiaroscuro effects. The clouds crashed together in brass-edged cymbals of purple and rust, and the mountains, vivid green below and black above, seemed to rise straight out of the sea. But after being lashed with freezing rain for half an hour, I was too numb to properly appreciate the splendor of the ongoing, ever-darkening sunset, and had to retreat to the cafeteria.

In Viking days, of course, I wouldn't have had that option.

Transatlantic voyages took place mainly in the summer months, but as I'd come to realize, summer in the North couldn't always be depended on. The

Laxdæla Saga

tells us that Aud's journey went well, though when they made land in the south of Iceland, their ship was wrecked. Most of the crossings from Norway or the Faroes to Iceland and back again were successful. Yet the sagas report enough stories of disaster and shipwreck to remind us what a hazardous journey it could be. I considered this as I sat at a table in the cafeteria with a bowl of soup before me. Outside rain slashed and slammed against the windows, and a murky purple dimness surrounded our ship. The jagged peaks of the Faroes began to recede until we were out of sight of land.

The flexible

hafskip

rarely swamped or foundered, for the simple reason that the sailors kept the prow to the waves. When a fair wind was blowing, the ship could make good time, but when the fair wind stopped or was replaced by squalls and contrary winds, or worse, thick fog, a ship might drift for weeks in the open sea. Sailors who lost their bearings were said to be in a state of

hafvilla.

As the

Laxdæla Saga

tells us in the story of another voyage: “They met with bad weather that summer. There was much fog, and the winds were light and unfavorable, what there were of them. They drifted far and wide on the high sea. Most of those on board completely lost their reckoning.”

Dead reckoning was one of the main methods of Norse navigation. Over a long sea voyage, sailors were able to keep a remarkably good record of where they were and how far they had come. With a fair wind they could travel 144 nautical miles a day. In summer they used the sun to give them their latitudinal bearings, and in spring and fall, the pole star. When in sight of land they were careful to note distinctive landmarks and commit them to memory. They also noticed varieties of sea

birds and whales to give them a sense of how far north they were. Icebergs, unwelcome as they were, oriented them as well.