The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain

Read The Plantagenets: The Kings That Made Britain Online

Authors: Derek Wilson

Tags: #HISTORY / Europe / Great Britain, #Fiction

Contents

- The Plantagenet Succession

- Introduction

- Henry II

- Richard I And John

- Henry III

- Edward I

- Edward II

- Edward III

- Richard II

- Henry IV

- Henry V

- The Wars Of The Roses

- Edward IV, Edward V and Richard III

- Postscript

- References

- Picture Credits

THE PLANTAGENETS

THE KINGS THAT MADE BRITAIN

DEREK WILSON

New York • London

© 2014 by Derek Wilson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to

[email protected]

.

e-ISBN 978-1-62365-591-4

Distributed in the United States and Canada by

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10104

Derek Wilson is one of Britain’s leading popular historians. Since leaving Cambridge, where he took the Archbishop Cranmer Prize for post-graduate research, he has written over 70 books including

Britain’s Rottenest Years

,

Rothschild: A Story of Wealth and Power

, and

Hans Holbein: Portrait of an Unknown Man

, as well as making numerous radio and TV appearances. He lives in Devon.

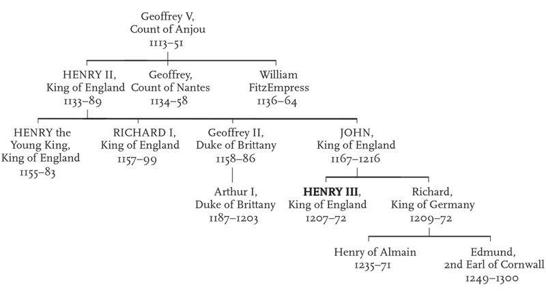

The Plantagenet Succession

The Plantagenet Succession

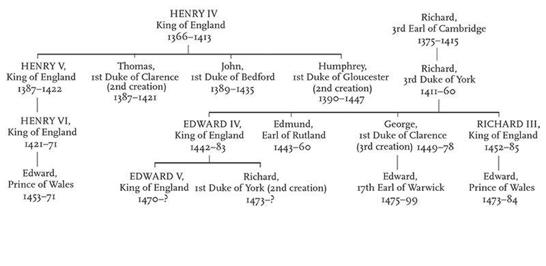

(Cont.)

The Plantagenet Succession

(Cont.)

The Plantagenet Succession

(Cont.)

INTRODUCTION

The 331 years during which kings of the Plantagenet or Angevin line ruled England might almost be written as the history of that strip of water known to Britons as the English Channel and to the French as La Manche. What seems to us obvious – that Britain is an island nation, with a distinct identity, whose language, culture and politico-legal system distinguish it from its continental neighbours – would have been incomprehensible to the subjects of Henry II.

England was part of western Christendom, a civilization extending from the Atlantic seaboard to the Carpathians and the Danube basin, beyond which lay lands where Byzantine Christianity, Islam or heathendom held sway. Its ideological centre was Rome, from where the pope exercised a very real influence over temporal rulers.

Throughout this large area there was one common language, Latin, which was spoken and written by all members of the educated class (which, for the most part, meant the clergy) and familiar to (though meagrely understood by) the peasants who attended mass in their parish church. All legal documents were written in Latin, much diplomatic interchange was conducted in Latin, and the chronicles of past and contemporary events, upon which

historians rely heavily, were set down in Latin by monks working in the scriptoria of their monasteries. The influence of the church was not confined to the spiritual and intellectual realms – it was far and away the biggest landowner in Europe. Over the centuries pious benefactors had donated or bequeathed to monasteries and bishoprics estates, villages and farmsteads (together with the inhabitants thereof). Abbots and bishops were, in a very real sense, ‘princes’ of the church, enjoying wealth and splendour that rivalled that of aristocrats and even kings. And ‘rivalled’ is an apt word, for temporal and spiritual magnates were in frequent conflict, asserting their rights in parliament and the law courts.

England was also part – and not the most important part – of the Angevin empire. Henry II commanded a territory that embraced most of what we now know as western France. The language of the royal court was Norman French. The empire had been compiled through the warfare, marriage and diplomatic negotiation that constituted international relations. ‘Europe’ was a fluid reality, shaped by the competing ambitions of kings and feudal princelings. The feudal system was simple in theory but increasingly complex in reality. All land was held from the king by tenants-in-chief in return for military service. They sub-let to others, again in return for whatever services they demanded. Government and law were in the hands of the feudal lords and exercised through royal and manorial courts. While theoretically obligated to the king as liege lord, territorial magnates strove to achieve

de facto

independence. Thus, the king of France only ruled directly the Ile de France and Orleanais, an area centred on

the middle Seine and Loire valleys. Successive kings were engaged in extending and consolidating their real power. The parcel of dukedoms stretching from the Channel to the Pyrenees, which constituted the Angevin empire, were held as feudatories of the French crown. The Plantagenet rulers were constantly under two forms of pressure: from the French king and from the territorial magnates eager to wrest power from their overlord.

England differed from other parts of the Angevin empire in two important respects. It was a conquered country. Henry II’s great-grandfather, William the Conqueror (William I), had brutally overrun the land almost a century earlier and divided it into fiefs governed by his own trusted Norman followers. He had firmly established royal authority and based his government on jurisdictional and fiscal officers answerable to the crown. Thus, although tensions between king and magnates existed in England as on the continent, there the tenants-in-chief had no tradition of regional power built up over several generations.

England’s other difference was, of course, that it was separated from the continent by a stretch of water that constituted a formidable barrier to invasion. Armies could move with comparative ease between Gascony, Poitou, Anjou, Maine and Normandy, but transporting them across the Channel was a complex and costly logistical exercise. This worked in the Angevins’ favour. While an invader had to bring all his troops and supplies with him, the English king, when campaigning on the continent, could call on the support of his subjects there. This advantage was offset by

the difficulty of ruling territory on both sides of the water. Angevin kings were, perforce, peripatetic, ever on the move in their attempts to hold their inheritance together. In the end this proved impossible, and by the time the last Plantagenet came to power the continental empire had all but gone. He only had the toe-hold of Calais left on the European mainland.