The Pleasure of My Company (12 page)

Read The Pleasure of My Company Online

Authors: Steve Martin

“Thank

you for letting us stay here. We’ll look for somewhere else tomorrow.”

“You

can stay here as long as you need to,” I said.

“We

might need to stay here tomorrow. I called his sister. She told me he’s got to

be back in Boston on Saturday. If he goes, we’ll be all right.”

Clarissa

squeezed my elbow and then stood up. “Do you want me to turn out the lights?”

she asked.

“No,” I

said, “I want to read.” There wasn’t a book nearby and I had never told her of

my wattage requirements, so she looked around, momentarily puzzled. But this

was such a tiny bewilderment at the end of doomsday it hardly mattered. She

retreated into the bedroom, leaving the door cracked open.

As

midnight closed in on us, the extraneous sounds of televisions and cars,

footsteps and distant voices unwove themselves from the night. I closed my

eyes. The light no longer bothered me. I thought of the two women in my bed and

the protective sandwich they made that held Teddy in place. My body curled and

tightened as if being pulled by a drawstring. I gasped for breath. I pictured

myself spread over Teddy like a blanket, but I was watching from above, just as

Clarissa watched herself from heaven. The kicks intended for Teddy were taken

and absorbed by my body. There was something about having intervened at the

exact moment of heartbreak that evoked a deepening melancholy, and I hiccupped

a few sobs. I then saw myself as the boy, hearing and sensing the blows from

overhead, and why did I, rolled up on the sofa clutching a pillow, say out

loud, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry”?

I heard a few small

wahs

during the night, a few footsteps pattering around, and I think we all had

a fitful sleep. By 5 A.M., however, nothing stirred except my eyeballs, which

delighted in having a fresh ceiling to dissect. Silence had finally struck

Santa Monica, which put my mind in the opposite of a Zen state. Rather

than my head being empty

of thought, every crevice was bursting with facts, numbers, revelations,

connections, and products. After I had deduced, or more properly, induced how Aquafresh

striped toothpaste is coaxed into the tube back at the factory, I created a new

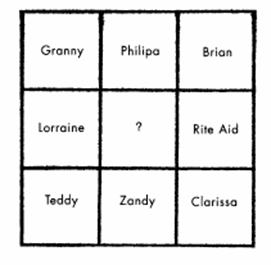

magic square:

I was lost in the vision

of the square, this graphic of my current life, when one of its components,

Teddy, creaked open my bedroom door and crawled a few feet into the living

room, pausing on all fours. The component looked over at me and grinned. He

then made a surprising feint right but went left, then pulled himself up and

leaned against the wall, moving his eyes off me only for necessary seconds. He

turned and pressed his palms against the wall and then circumnavigated the room

until he had gotten to the sofa where I was trying so hard to sleep. He plopped

back on his rear end and extended his arms toward me, which I supposed to be

some sort of cue for me to pick him up, and I did. I placed him on my chest,

where he sat contentedly for about a minute, and I said something that had an

intentional abundance of the letter

b

in it, as I thought the letter

b

might be amusing to a one-year-old. I started with actual words—baby,

booby, bimbo—then degenerated into nonsense sounds: bobo, boobah, beebow. His

expressions ranged from concentration, to displeasure, to happiness, to confusion,

to distress, though as far as I could tell, there was absolutely nothing to

feel displeasure, happiness, confusion, or distress about. Except for the

letter

b.

I put

my hand on his stomach to tickle him and found that my palm extended over his

entire rib cage. I picked him up and hoisted him above my head, balancing him

in the air on my stiff right arm, which he seemed to relish. I twisted him from

side to side and he spread his arms, and for a few moments he was like an

airplane on a stick. This simulation of flight seemed to please him inordinately,

and his mother, who must have sensed that her boy had gone missing, said from

over my shoulder, “Are you flying, Teddy? Are you flying in the air?”

In the

morning, they slipped away like a caravan leaving an oasis, and the return to

quiet unnerved me.

The next few days were

stagnant. I was distressed to think that my regular visits from Clarissa were

over. I wondered how I was going to fill those two hours that had become the

binary stars around which my week revolved. I was also concerned for Clarissa,

who had not contacted me in several days. I wondered if I had been ostracized

from the group because I represented a horrible memory. But on the day and

almost the hour of my regular visit, I saw Clarissa crossing the street with

Teddy, carrying him under her arm like a gunnysack full of manure. Her other

arm toted a cloth bag stuffed with baby supplies that bloomed and poked out of

its top.

I

opened the door and started to say the

h

in hello, but she cut me off

with, “Could I ask you a favour?” The request held such exasperation that I

worried she had used up all the reserve exasperation she might need on some

other occasion. “Could you watch Teddy for a couple of hours?” Without saying

anything I came down the stairs and relieved her of the boy. I then understood

why she had carried him like a sack of manure. “He needs changing,” she said.

And

how,

I thought. Going in my apartment, Clarissa added, “I’ll change him

now and that should hold him.” Clarissa, who was clearly on the clock, rushed

the diaper change, pointed to a few toys to waggle in front of him, gave me a

bottle of apple juice, wrote down her cell phone number, tried to explain her

emergency, said she would be back in two hours, added that Lorraine had gone

back to Toronto, kissed Teddy good-bye, hugged me good-bye, and left.

Thus I

went from being Clarissa’s patient to becoming her son’s baby-sitter.

Teddy

and I sat on the floor and I poured out the contents of the bag, which included

a twelve-letter set of wooden blocks. These blocks were the perfect amusement

for us, because while Teddy was fascinated with their shape, weight, and sound

as they knocked together, I was fascinated with the vowels and consonants

etched in relief on their faces. It was not easy to make words with this

selection. Too many C’s, B’s, G’s, X’s and Y’s, and not enough A’s,

E’s,

and

I’s. So while he struggled to build them up, I struggled to arrange them

coherently. Whatever I did, Teddy undid; when he toppled them, I rebuilt them,

and when he stacked them haphazardly, I rearranged them logically. Two hours

went by and when Clarissa returned, she found us in the middle of the floor,

transfixed.

Two

days later, I agreed to watch Teddy from four to six and she offered to pay me

five dollars an hour, which I refused.

Occasionally I amuse

myself by imagining headlines that would trumpet the ordinary events of my day.

“Daniel Pecan Cambridge Buys Best-Quality Pocket Comb.” “Santa Monica Man

Reties Shoe in Mid-Afternoon.” I imagine these headlines are two inches high

and I picture citizens standing on street corners reading them with a puzzled

expression. But the headline that was now in my mind was prompted by a letter

from Tepperton’s Pies, which I pinched between my stunned thumb and bewildered

forefinger: “Insane Man Chosen as Most Average American.” The letter began with

“Congratulations!” and it told me that I had won the Tepperton’s Pies essay

contest. It went on to describe my duties as the happy winner. I was to walk

alongside the runners-up in a small parade down Freedom Lane on the campus of

Freedom College. We would then enter Freedom Hall, walk on the stage, and read

our essays aloud, after which I would be presented with a check for five thousand

dollars.

I was

getting a little nervous about the letter’s frequent repetition of the word “Freedom.”

It could be an example of a small truth I had uncovered in my scant thirty-five

years of life: that the more a word is repeated, the less likely it is that the

word applies. “Bargain,” “only,” “fairness,” are just a few, but here the word “Freedom”

began to smell like Teddy’s underpants. But what difference did it make? I am

not a political person—in college I voted for president of the United States.

He promptly lost and I never wanted to jinx my candidate again by voting for

him. But whatever was the political underbelly of Freedom College, I was going

to make five thousand dollars for reading an essay aloud.

That

week I practiced reading my essay by enlisting Philipa to listen to a few dry

runs and coach me. Her contribution turned out to be so much more than just a

few pointers. Philipa saw it as an opportunity to express to someone, anyone,

just how complicated the simplest performance can be. She told anecdotes, got

mad, complimented me, sulked, screamed “Yes!” and generally took it all way

too far. Her goal was to impress upon someone, anyone, mainly herself, just how

difficult her work was, that a nobody like me needed professional guidance. She

almost had me convinced, too, until I realized I was much better when she wasn’t

in the room.

Friday

came and Clarissa dropped off Teddy with a warm thank-you and a bundle of

goodies. She gave me a hug that I had trouble interpreting. It could have been,

at its highest level, a symbolic act indicating her deepening love for me; at

its worst, well, there was no worst, because at its lowest level, it was

symbolic of the trust she’d bestowed on me as the temporary guardian of her

child. When she left, Teddy burst into tears and I held him up at the window so

he could see her. I’m not sure if it was a good idea, because no matter what

spin I tried to put on it, he was still looking at his mother leaving. Left

alone with Teddy, I then began the game of Distraction and Focus. The object of

the game was to Focus Teddy on something he liked and to Distract him from

something he didn’t. That afternoon I discovered a law that states that for

every Focus there is an equal and opposite Distraction and that they parse into

units of equal time. Five minutes of Focus meant that somewhere down the line

waited five minutes of Distraction.

Within

the first hour, I had exhausted my repertoire of funny faces and their

accompanying nonsensical sounds. I had held up every unique object in my

apartment. I had taken him on my forearm seat and marched him around to every

closet, window cord, and cabinet pull. We had stacked and restacked the

wretched wooden blocks. In a desperate move, I decided to take him down to the

Rite Aid, which I remembered had a small selection of children’s toys, and I

was hoping that Teddy, the man himself, would indicate exactly which of them

would put an end to his frustration.

There

was about an hour of daylight left and I toddled him down my street to the

first opposing driveways of my regular route. I had a moment of concern about

crossing with him in the middle of the street but decided that extra care in

looking both ways would ease my mental gnaw. And so Teddy became the first

human ever to accompany me on my tack to the Rite Aid. He, of course, had no

questions, no quizzical looks, no backsteps indicating he thought I was nuts,

and I felt almost as if I were cheating: It seemed to me that if one is crazy,

it’s unfair to involve someone who doesn’t understand the concept. If, as the

books say, my habits exist to keep demons at bay, what was the point of

exhibiting them in front of someone who was so clearly not a demon? Who, in

fact, was so clearly a demon’s opposite?

It was

dusk, and the interior of the Rite Aid was bathed in its own splendid white

light, which democratically saturated every corner of the store. The light was

reflected from the polished floors and sho-cards so evenly that nothing had a

shadow. I held Teddy’s hand as I led him down the aisles, heading for the toy

section. We passed a display of crackers that held him enthralled, and it took

some doing to lure him away from those elephantine red boxes spotted with

orange circles and blue borders. As I cajoled him with head nods and

high-pitched promises of the delights that awaited us just around the aisle, I

noticed Zandy looking directly at us from her high perch in Pharmacy. She didn’t

do anything, including looking away. A customer intervened with a question. She

turned toward him, and in the second it took to shift her attention, she turned

her face back to me and emitted one silent, happy laugh.

I now

had Teddy moored in front of a hanging display of games and toys, and not only

did I show him everything, I presented each prospect as though it were a tiara

on a velvet pillow. And he, like a potentate reviewing yet another slave girl,

rejected everything. He kept looking back and mewing and, unable to point,

threw open his palm with five fingers indicating five different directions.

Somehow, and I’m not sure telepathy was not involved, he navigated us back to

crackers. This was his choice, and I saw that it was a good one, because what

was inside was textural, crushable, and finally, edible.