The Portable Veblen (40 page)

Read The Portable Veblen Online

Authors: Elizabeth Mckenzie

“He’s here in the ICU?” Chaudhry asked, and when she told him why, he was stunned. “That takes the cake.”

“Definitely.”

“Veblen, I’m very sorry. Please take all the time you need.”

“Thanks.”

She returned to Paul’s room, and Dr. Chaudhry came by an hour later. He’d conferred with the doctors in the ICU and been told that Paul’s prognosis was good. Then Laurie Tietz came by with a large latte and a big blueberry muffin, and gave her a long, warm hug.

• • •

8 A.M.

Veblen sat beside Paul thinking of ways to cheer him up. She picked up the telephone by the bed as if a call had come in. She said, “What are you selling? Life membership in the golf and country club?

Errrghhhhhhhhhhhhhlllll

—” She gurgled and retched and hung up in burlesque fashion. When there was no response she added, “Remember you said you liked it when I did that? I hope you remember.

“I can’t wait to go to Tacos Tambien as soon as you’re better.

Carnitas!

Lime! Cilantro! Yeah!”

No reaction. Nothing at all.

“Let’s share more grievances,” she tried. “I’ve been way too uptight about that. What was I afraid of?” She stopped a moment to find something unpleasant Paul had tried to share with her. “You know, I hate smelly hippies with bags of excrement in tree houses too. Have I ever told you that?”

Nothing. “Paul, and you know what else I can’t stand?

Nudists

. And you know why? The

ist

part. Give me an ecologist, a violinist, an artist. But if you’re just a nudist, get a life, you know what I mean?”

She checked the monitor—to her disgust for nudists, his vitals showed no response.

“Turkey balls aren’t as good as regular meatballs, you’re absolutely right, and I’ll never make them again, so help me god.”

She looked at him closely.

“And what’s so great about corn on the cob, compared to love?”

Saying

love,

Veblen felt something break inside herself that was brilliant and deafening, a desperate roar. It was a pinch, a crack, a tear. It was roaring, sweeping, aching, bending, a torrent carrying her away.

• • •

8:20 A.M.

“You know, I’ve been thinking about you and Justin and—from the outside it’s easy to be judgmental but—it was

your

childhood too—” Paul twitched, and maybe she’d hit a nerve. “It’s uncool when he steals people’s underwear, definitely. And you know how they call themselves a tripod? Well, that’s so cruel and unfair to you! It hurts just thinking about it.”

She looked up and saw Bill and Marion standing behind her, confused and wounded by what they had heard.

“Oh! But I hope—don’t take it the wrong way!”

They retreated quietly, and her instinct was to regain their approval, to follow and mend. But she didn’t.

“Paul, I’ve alienated both of our families. Ha! The way you wanted it. Now it’s just us.”

• • •

11:00 A.M.

Paul’s colleague James Shalev stopped by. He told Veblen he’d been part of the trial from the start, and now that he’d witnessed the accident, he felt like he had something to say about the whole symbiotic FDA / pharmaceutical industry / DOD triumvirate that wasn’t exactly positive.

“I was with him at DeviceCON the night he found out his device was out. It was mind-blowing. We even talked about it being risky, like in

The Fugitive

. Unbelievable. He’s a hero.”

“Thank you,” Veblen said.

• • •

11:30 A.M.

Paul’s friend Hans showed up; he’d heard the news from the Vreelands.

“Hey, Veblen,” he said, embracing her. “He knew this was about to happen, and he told me to take care of you if it did.”

Veblen listened, a lump in her throat.

“I’ve already written down everything he said to me that

morning and put it in a safe place. I’ll be the first person up on the stand to testify. He’s my man.”

“Mine too,” Veblen said.

• • •

12:00 NOON

Linus came in carrying a bag. “So what’s the news?”

“It’s wait and see,” Veblen said. “He’s stable. Where’s Mom?”

“She’s out in the car. She’s a little shaky. She is upset and doesn’t want to make it worse by coming inside. But she wants me to tell you she’s standing by. We’re going home today but she’ll be waiting by the phone, of course.”

“Fine,” Veblen said.

“Here’s a bite to eat, we picked up some items at that bakery you like,” Linus said.

“Thank you.”

Linus shook his head. “This is a terrible thing, babe. Is there anything I can do?”

“I’m sorry I attacked you last night,” she said, and hugged him.

“There, there,” Linus said. “I’d blow my top too, if you or Melanie were hurt. I’m going to take your mother home now and you call later when you can, all right?”

“All right.”

• • •

T

HE DAY WAS LONG

and dreadful. Whenever his eyelids flickered, she wondered if he was seeing the world like a newborn, “one great blooming, buzzing confusion,” as William James imagined it.

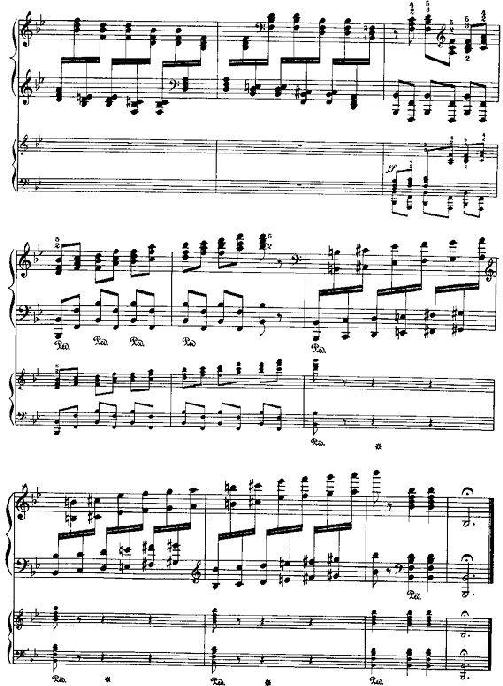

She remembered a concert they had attended in San Francisco one evening in the fall, shortly after they met. The program included three concertos, and ended with Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto no. 1 in B-flat minor, op. 23. It is the showy yet rousing concerto heard when advertising any pianist’s greatest hits. And Veblen kept waiting for the theme at the beginning to return, but it never did, which was a buzzing confusion to her untrained ears.

ENDING OF PETER ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY’S PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 IN B-FLAT MINOR, OP. 23.

Paul stood in ovation as the young pianist took his bows. “My god, that ending,” he said, in awe. “That’s probably my favorite finale in all of classical music.”

She had been puzzled. “Really? In

all

of classical music?”

“The way it builds. It’s just about perfect.”

It was a moment in which she sensed unplumbed depths in him, and a minefield of shallows in herself. She’d have to listen to it again. To everything again.

• • •

S

HE USED TO THINK

falling in love was alchemy, that animals had weddings, that coal was a gemstone, that mountains were hollow, that trees had hidden eyes!

• • •

T

HE FOLLOWING MORNING,

just as Veblen pushed up from the cot, as the new shift began to bustle, she heard a voice say, “I’d kill for a cup of coffee.”

She looked up. Paul’s eyes were open, and he smiled, as if there were nothing strange about being attached to an IV with a cannula in his hand, his head fully wrapped, his leg in a full cast, a profusion of tape all over his chest, cardiac monitors and brain monitors beeping and signaling on a nearby screen, a catheter lodged deep in his urethra.

“Paul!”

“I guess something bad must have happened,” he said.

21

C

AN

Y

OU

P

ATENT

THE

S

UN

?

S

o,” Veblen said. “Not just bad, but also weird.”

Paul took her hand. “Very weird.”

Paul was out of the ICU, in another room resting after a battery of tests. According to Dr. Munoz, there were excellent N20 components in his evoked potentials. His corneal reflexes were first-rate. His extensor motor responses were superb. There had been no myoclonus status epilepticus whatsoever. His neuron-specific enolase levels were below thirty-three micrograms per liter. His creatine kinase brain isoenzyme was within range. Brain oxygenation and intracranial pressure were normal. He had retrograde amnesia about the immediate circumstances of the accident, but that was thoroughly anticipated by Ribot’s law. He scored VIII on the Rancho Scale for postcoma recovery, the highest possible. He was “appropriate and purposeful.” Yet the more he remembered and the clearer his mind became, the more ill at ease he felt.

He began to insist that he must leave the medical profession. That he must find something entirely new.

Veblen let him say such things, as if he needed to drain himself of a poison.

He remembered writing the letter about the discrepancies in the trial, but could not piece together what happened next. There was something nightmarish on the periphery, some obviously false memory of a struggle. Sure enough, Veblen reminded him he had visited the simulator just before the accident. That was where he’d dropped his letters. Paul said, “Then that simulator is something else. I have this strange impression of being in some kind of hand-to-hand combat.”

“Visitors,” the nurse announced.

Veblen looked to the door. Two young women came in, escorting a well-built man shuffling with the aid of a cane.

“Sorry, is this a good time?” one of the young women asked. “We don’t want to bother you.”

“No, come in,” Veblen said, and they introduced themselves as Sarah and Alexa Smith, their father as Warren Smith, a veteran who had been a participant in Paul’s trial.

Paul sat up stiffly and placed his hands over his neck.

Sarah said, “See, Dad? Dr. Vreeland is okay. See?”

Smith squinted at Paul, then turned for the door.

“Our father has something to say,” Alexa said. “Dad, get out your coping cards, remember?”

Smith stopped and pulled some index cards from his jacket pocket.

“Go ahead, Dad. It’s okay,” Sarah said.

Smith began to read: “What happened was a mistake, and I apologize for that. I take full responsibility for my aggressive, impulsive, and insensitive behavior. I have a history of blaming others

for my problems, and this needs to stop. I take responsibility for causing you pain.”

Smith finished. He folded up his cards and returned them to his pocket, then turned again for the door.

“Pain?” Paul said. “You’re Sergeant Major Smith, am I right?”

Smith stopped and nodded.

“I appreciate your kind words, but really, you have nothing to apologize for, do you?”

“Let’s go,” said Warren Smith.

“Well, that’s nice of you,” said Alexa. “Um, also, we feel really bad telling you this, but we’re not selling the Sea Ray, right, Dad?”

“The Sea Ray!” Paul nodded. “Well, I guess that didn’t prove to be the most popular idea. Good luck with everything then.”

“You too, Dr. Vreeland, you take care!”

They shuffled out with their father.

“What did he do to you?” Veblen wanted to know.

“I have no idea,” Paul said, still rubbing his neck. “Come here. I can’t believe what I’ve put you through.”

“Don’t even think about it.”

“I wish I could remember it better. Cloris really tried to kill me?”

“She hit you with her car,” Veblen confirmed.

“There’s something about Cloris Hutmacher I’ve never liked,” Paul said shrewdly.

He drank some water through a straw, then said, “In Vienna in the late 1800s, there was this medical-device-maker guy, Erwin Perzy, and he tried to invent a surgical lamp that would be brighter than the bulbs they were using at the time. He knew that setting a candle behind a glass of water enhanced the light, so he started playing around encasing bulbs in globes of water, then adding

tinsel and white sand for reflection. It didn’t work for lamps, but you know those things called snow globes?”

“Yeah.”

ERWIN PERZY I, INVENTOR OF SNOW GLOBES.

“That’s what he ended up inventing. To this day, that’s what he’s known for.”

“Really! That’s a great thing to be known for. I love snow globes. They’re way better than surgical lamps.”

“Not if you’re having surgery.”

“But, Paul, your device works and it’s still going to do all the things you hoped it would.”

In statements issued through Hutmacher’s attorneys, Shrapnal and Boone, Cloris claimed that Paul threw himself in her path, and that the accident had nothing to do with the allegations in Paul’s letter, nor with the research materials for the trial found in the boxes in her backseat. An investigation was under way.