The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business (45 page)

Read The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business Online

Authors: Charles Duhigg

Tags: #Psychology, #Organizational Behavior, #General, #Self-Help, #Social Psychology, #Personal Growth, #Business & Economics

In the prologue, we learned that a habit is a choice that we deliberately make at some point, and then stop thinking about, but continue doing, often every day.

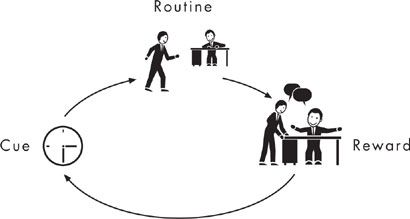

Put another way, a habit is a formula our brain automatically follows: When I see CUE, I will do ROUTINE in order to get a REWARD.

To re-engineer that formula, we need to begin making choices again. And the easiest way to do this, according to study after study, is to have a plan. Within psychology, these plans are known as “implementation intentions.”

Take, for instance, my cookie-in-the-afternoon habit. By using this framework, I learned that my cue was roughly 3:30 in the afternoon. I knew that my routine was to go to the cafeteria, buy a cookie, and chat with friends. And, through experimentation, I had learned that it wasn’t really the cookie I craved—rather, it was a moment of distraction and the opportunity to socialize.

So I wrote a plan:

At 3:30, every day, I will walk to a friend’s desk and talk for 10 minutes.

To make sure I remembered to do this, I set the alarm on my watch for 3:30.

It didn’t work immediately. There were some days I was too busy and ignored the alarm, and then fell off the wagon. Other times it seemed like too much work to find a friend willing to chat—it was easier to get a cookie, and so I gave in to the urge. But on those days that I abided by my plan—when my alarm went off, I forced myself to walk to a friend’s desk and chat for ten minutes—I found that I ended the workday feeling better. I hadn’t gone to the cafeteria, I hadn’t eat a cookie, and I felt fine. Eventually, it got be automatic: when the alarm rang, I found a friend and ended the day feeling a small, but real, sense of accomplishment. After a few weeks, I hardly thought about the routine anymore. And when I couldn’t find anyone to chat with, I went to the cafeteria and bought tea and drank it with friends.

That all happened about six months ago. I don’t have my watch anymore—I lost it at some point. But at about 3:30 every day, I absentmindedly stand up, look around the newsroom for someone to talk to, spend ten minutes gossiping about the news, and then go back to my desk. It occurs almost without me thinking about it. It has become a habit.

Obviously, changing some habits can be more difficult. But this framework is a place to start. Sometimes change takes a long time. Sometimes it requires repeated experiments and failures. But once you understand how a habit operates—once you diagnose the cue, the routine and the reward—you gain power over it.

John and Doris,

and, everlastingly, to Liz

I have been undeservedly lucky throughout my life to work with people who are more talented than I am, and to get to steal their wisdom and gracefulness and pass it off as my own.

Which is why you are reading this book, and why I have so many people to thank.

Andy Ward acquired

The Power of Habit

before he even started as an editor at Random House. At the time, I did not know that he was a kind, generous, and amazingly—astoundingly—talented editor. I’d heard from some friends that he had elevated their prose and held their hands so gracefully they almost forgot the touch. But I figured they were exaggerating, since many of them were drinking at the time. Dear reader: it’s all true. Andy’s humility, patience and—most of all—the work he puts into being a good friend make everyone around him want to be a better person. This book is as much his as mine, and I am thankful that I had a chance to know, work with, and learn from him. Equally, I owe an enormous debt to

some obscure deity for landing me at Random House under the wise guidance of Susan Kamil, the leadership of Gina Centrello, and the advice and efforts of Avideh Bashirrad, Tom Perry, Sanyu Dillon, Sally Marvin, Barbara Fillon, Maria Braeckel, Erika Greber, and the ever-patient Kaela Myers.

A similar twist of fortune allowed me to work with Scott Moyers, Andrew Wylie, and James Pullen at the Wylie Agency. Scott’s counsel and friendship—as many writers know—is as invaluable as it is generous. Scott has moved back into the editorial world, and readers everywhere should consider themselves lucky. Andrew Wylie is always steadfast and astute in making the world safer (and more comfortable) for his writers, and I am enormously grateful. And James Pullen has helped me understand how to write in languages I didn’t know existed.

Additionally, I owe an enormous amount to the New York Times. A huge thanks goes to Larry Ingrassia,

The Times

’ business editor, whose friendship, advice and understanding allowed me to write this book, and to commit journalism among so many other talented reporters in an atmosphere where our work—and

The Times

’ mission—is constantly elevated by his example. Vicki Ingrassia, too, has been a wonderful support. As any writer who has met Adam Bryant knows, he is an amazing advocate and friend, with gifted hands. And it is a privilege to work for Bill Keller, Jill Abramson, Dean Baquet and Glenn Kramon, and to follow their examples of how journalists should carry themselves through the world.

A few other thanks: I’m indebted to my

Times

colleagues Dean Murphy, Winnie O’Kelly, Jenny Anderson, Rick Berke, Andrew Ross Sorkin, David Leonhardt, Walt Bogdanich, David Gillen, Eduardo Porter, Jodi Kantor, Vera Titunik, Amy O’leary, Peter Lattman, David Segal, Christine Haughney, Jenny Schussler, Joe Nocera and Jim Schacter (both of whom read chapters for me), Jeff

Cane, Michael Barbaro and others who have been so generous with their friendship and their ideas.

Similarly, I’m thankful to Alex Blumberg, Adam Davidson, Paula Szuchman, Nivi Nord, Alex Berenson, Nazanin Rafsanjani, Brendan Koerner, Nicholas Thompson, Kate Kelly, Sarah Ellison, Kevin Bleyer, Amanda Schaffer, Dennis Potami, James Wynn, Noah Kotch, Greg Nelson, Caitlin Pike, Jonathan Klein, Amanda Klein, Donnan Steele, Stacey Steele, Wesley Morris, Adir Waldman, Rich Frankel, Jennifer Couzin, Aaron Bendikson, Richard Rampell, Mike Bor, David Lewicki, Beth Waltemath, Ellen Martin, Russ Uman, Erin Brown, Jeff Norton, Raj De Datta, Ruben Sigala, Dan Costello, Peter Blake, Peter Goodman, Alix Spiegel, Susan Dominus, Jenny Rosenstrach, Jason Woodard, Taylor Noguera, and Matthew Bird, who all provided support and guidance. The book’s cover, and wonderful interior graphics, come from the mind of the incredibly talented Anton Ioukhnovets.

I also owe a debt to the many people who were generous with their time in reporting this book. Many are mentioned in the notes, but I wanted to give additional thanks to Tom Andrews at SYPartners, Tony Dungy and DJ Snell, Paul O’Neill, Warren Bennis, Rick Warren, Anne Krumm, Paco Underhill, Larry Squire, Wolfram Schultz, Ann Graybiel, Todd Heatherton, J. Scott Tonigan, Taylor Branch, Bob Bowman, Travis Leach, Howard Schultz, Mark Muraven, Angela Duckworth, Jane Bruno, Reza Habib, Patrick Mulkey and Terry Noffsinger. I was aided enormously by researchers and fact checkers, including Dax Proctor, Josh Friedman, Cole Louison, Alexander Provan and Neela Saldanha.

I am forever thankful to Bob Sipchen, who gave me my first real job in journalism, and am sorry that I won’t be able to share this book with two friends lost too early, Brian Ching and L. K. Case.

Finally, my deepest thanks are to my family. Katy Duhigg, Jacquie Jenkusky, David Duhigg, Toni Martorelli, Daniel Duhigg, Alexandra

Alter, and Jake Goldstein have been wonderful friends. My sons, Oliver and John Harry, have been sources of inspiration and sleeplessness. My parents, John and Doris, encouraged me from a young age to write, even as I was setting things on fire and giving them reason to figure that future correspondence might be on prison stationary.

And, of course, my wife, Liz, whose constant love, support, guidance, intelligence and friendship made this book possible.

—September, 2011

The reporting in this book is based on hundreds of interviews, and thousands more papers and studies. Many of those sources are detailed in the text itself or the notes, along with guides to additional resources for interested readers.

In most situations, individuals who provided major sources of information or who published research that was integral to reporting were provided with an opportunity—after reporting was complete—to review facts and offer additional comments, address discrepancies, or register issues with how information is portrayed. Many of those comments are reproduced in the notes. (No source was given access to the book’s complete text—all comments are based on summaries provided to sources.)

In a very small number of cases, confidentiality was extended to sources who, for a variety of reasons, could not speak on a for-attribution basis. In a very tiny number of instances, some identifying characteristics have been withheld or slightly modified to conform with patient privacy laws or for other reasons.

PROLOGUE

prl.1

So they measured subjects’ vital signs

Reporting for Lisa Allen’s story is based on interviews with Allen. This research study is ongoing and unpublished, and thus researchers were not available for interviews. Basic outcomes, however, were confirmed by studies and interviews with scientists working on similar projects, including A. DelParigi et al., “Successful Dieters Have Increased Neural Activity in Cortical Areas Involved in the Control of Behavior,”

International Journal of Obesity

31 (2007): 440–48; Duc Son NT Le et al., “Less Activation in the Left Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex in the Reanalysis of the Response to a Meal in Obese than in Lean Women and Its Association with Successful Weight Loss,”

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition

86, no. 3 (2007): 573–79; A. DelParigi et al., “Persistence of Abnormal Neural Responses to a Meal in Postobese Individuals,”

International Journal of Obesity

28 (2004): 370–77; E. Stice et al., “Relation of Reward from Food Intake and Anticipated Food Intake to Obesity: A Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Study,”

Journal of Abnormal Psychology

117, no. 4 (November 2008): 924–35; A. C. Janes et al., “Brain fMRI Reactivity to Smoking-Related Images Before and During Extended Smoking Abstinence,”

Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology

17 (December 2009): 365–73; D. McBride et al., “Effects of Expectancy and Abstinence on the Neural Response to Smoking Cues in Cigarette Smokers: An fMRI Study,”

Neuropsychopharmacology

31 (December

2006): 2728–38; R. Sinha and C. S. Li, “Imaging Stress-and Cue-Induced Drug and Alcohol Craving: Association with Relapse and Clinical Implications,”

Drug and Alcohol Review

26, no. 1 (January 2007): 25–31; E. Tricomi, B. W. Balleine, and J. P. O’doherty, “A Specific Role for Posterior Dorsolateral Striatum in Human Habit Learning,”

European Journal of Neuroscience

29, no. 11 (June 2009): 2225–32; D. Knoch, P. Bugger, and M. Regard, “Suppressing Versus Releasing a Habit: Frequency-Dependent Effects of Prefrontal Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation,”

Cerebral Cortex

15, no. 7 (July 2005): 885–87.

prl.2

“All our life, so far as it has”

William James,

Talks to Teachers on Psychology and to Students on Some of Life’s Ideals,

originally published in 1899.

prl.3

One paper published

Bas Verplanken and Wendy Wood, “Interventions to Break and Create Consumer Habits,”

Journal of Public Policy and Marketing

25, no. 1 (2006): 90–103; David T. Neal, Wendy Wood, and Jeffrey M. Quinn, “Habits—A Repeat Performance,”

Current Directions in Psychological Science

15, no. 4 (2006): 198–202.

prl.4

The U.S. military, it occurred to me

For my understanding of the fascinating topic of the military’s use of habit training, I am indebted to Dr. Peter Schifferle at the School of Advanced Military Studies, Dr. James Lussier, and the many commanders and soldiers who were generous with their time both in Iraq and at SAMS. For more on this topic, see Scott B. Shadrick and James W. Lussier, “Assessment of the Think Like a Commander Training Program,” U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Report 1824, July 2004; Scott B. Shadrick et al., “Positive Transfer of Adaptive Battlefield Thinking Skills,” U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Report 1873, July 2007; Thomas J. Carnahan et al., “Novice Versus Expert Command Groups: Preliminary Findings and Training Implications for Future Combat Systems,” U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Report 1821, March 2004; Carl W. Lickteig et al., “Human Performance Essential to Battle Command: Report on Four Future Combat Systems Command and Control Experiments,” U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences Research Report 1812, November 2003; and Army Field Manual 5–2 20, February 2009.

1.1

six feet tall

Lisa Stefanacci et al., “Profound Amnesia After Damage to the Medial Temporal Lobe: A Neuroanatomical and Neuropsychological Profile of Patient E.P.,”

Journal of Neuroscience

20, no. 18 (2000): 7024–36.