The Price of Blood (25 page)

Read The Price of Blood Online

Authors: Patricia Bracewell

A.D. 1009

The king went home, with the aldermen and the nobility; and thus lightly did they forsake the ships . . . Thus lightly did they suffer the labor of all the people to be in vain; nor was the terror lessened, as all England hoped. When this naval expedition was thus ended, then came, soon after Lammas, the formidable army of the enemy, called Thurkill’s army, to Sandwich . . .

—The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

Chapter Seventeen

June 1009

London

A

thelstan guided his mount through London’s crowded, noisome streets, and brooded on the circumstances that had landed him here on a bright summer’s morning: The king’s despair at the destruction of his mighty fleet; Eadric’s cunning in attaching all the blame for the disaster to the banished Wulfnoth and the dead Brihtric; the witan’s insistence that the remaining ships return to London; and finally his father’s surprising decision to place him in charge of the forlorn and decimated fleet. So while the king and court had limped off to Winchester to nurse their shattered nerves and blighted expectations, he had sailed up the Thames yestere’en with forty ships, charged to protect this city from whatever force might emerge from the Viking harbors across the sea.

But

good Christ

, he thought. They were taking a terrible risk! With all of the fleet anchored here, London would indeed be well protected, but it left the southern waters all but undefended. If the Danes should attack—and he had no doubt that they would strike, and soon—they would once again have their pick of weak coastal targets, from Canterbury to Exeter. The English could only hope that the forces ranged against them would be small and ill trained.

That seemed to him a forlorn hope. He could see no reason why some Danish warlord, or even King Swein himself, would not return with another great army to wrest what gold and silver they could from Britain. For the Danes it had become a way of life, and surely the news of the destruction of the English fleet must have reached the Danish ports by now. The Northmen would be climbing all over one another in their eagerness to board ships and set sail to plunder England.

He skirted the eastern end of the extensive, walled grounds of St. Paul’s and picked his way through the crowded stalls of the West Ceap. Some distance to his right he could see the palisade that surrounded the royal palace and the single English treasure that he coveted. It seemed incredible to him that after years of avoiding his father’s court and the temptation that was Emma, he was now charged by the king with her protection. If God meant to test him by putting the queen so firmly in his grasp, then God was a fool, for he would surely fail the test. He had tried to banish her from his mind, had taken other women in order to forget the one woman he could not have, but it had been an exercise in futility. He loved her still, unrepentant and unashamed, God help him.

Not for the first time, he wondered why Emma was still in London rather than in Winchester awaiting the arrival of the king. Why, for that matter, had she not attended the ship meet at Sandwich? Edyth had been there, accorded a privileged seat near the king. Surely that should have been Emma’s place. He had been troubled by her absence at the time, but the catastrophic events at Sandwich had driven all else from his mind.

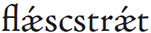

He pondered it now, though, searching unsuccessfully for an answer as he passed the reeking butchers’ stalls of the . For a time his mount, made fractious by the smell of blood, demanded all his attention, but soon enough he turned onto the wide lane that ran toward the Aldersgate and the northern road. Moments later he was riding between the square stone towers that marked the entrance to the palace.

. For a time his mount, made fractious by the smell of blood, demanded all his attention, but soon enough he turned onto the wide lane that ran toward the Aldersgate and the northern road. Moments later he was riding between the square stone towers that marked the entrance to the palace.

Ahead of him, on the broad track leading from the hall and royal chambers to the workshops and stables beyond, Emma stood on a mounting block beside her white mare. She was gowned in a robe of tawny wool that hung loose from her shoulders, and, seeing her profile limned by sunlight, he found the answer to the riddle he had posed himself.

The queen was pregnant, and that alone, he thought, was reason enough for her to forgo the rigors of a journey to Sandwich.

As he drew near she looked up and met his gaze. For an instant her studied reserve vanished and her face brightened in welcome. For an instant she was his alone. The silent acknowledgment of it flashed between them like quicksilver before it disappeared, and she assumed a far more solemn mask for the benefit of the servants and men-at-arms hovering about her.

He greeted her with matching formal courtesy and asked where she was bound.

“Out of the city to St. Peter’s,” she said. “The abbot is building a Lady Chapel to house a relic of the Virgin, and has invited me to inspect the progress he’s made. I could go another day, my lord, if you have pressing business with me.” She looked at him uncertainly. “Or would you care to accompany me?”

So he rode with her small company, slowly, through a gathering crowd, back around St. Paul’s and toward the Ludgate. Emma smiled and nodded to the folk who cheered lustily while several of her Norman guards distributed alms. Sometimes, he noted, the guards would stop and say a few words before depositing coins into eager palms.

Emma, he realized, was seeking the good opinion of the Londoners not just for herself, but for her Normans as well. His brother Edmund would have denounced this as devious and somehow sinister. He saw it as politic and farsighted. But then, he and Edmund never agreed on anything where Emma was concerned.

There was little opportunity for conversation as they passed through London’s western gate and out beyond the scattering of houses and shops that perched outside the city wall. Once they crossed the Fleet, though, the number of folk lining the road dwindled to nothing. As they passed fields of ripening grain he answered the questions that Emma posed about the events at Sandwich, and told her of the charge he had been given to organize London’s defense despite whatever suspicions his father harbored against him.

“The king must still place great trust in you,” she observed, “if he has given all of London into your care.”

“I suspect it is just the reverse,” he said, “and that my father has placed me in charge of London precisely because he does not trust me.”

She frowned at him. “I do not understand.”

“The king knows that whatever the temper in the rest of his realm, the men of London are fiercely loyal to him. The wealthiest landholders and merchants within the city are his thegns, and he has granted them rights and privileges that can be found nowhere else in the kingdom. I expect he is confident that nothing I could say or do would turn the Londoners against him, and so he has placed me here, where I can do him no harm. As for the city’s defense, what is left of our fleet is now anchored in the Thames below the bridge. Those forty ships will likely deter our enemies from attempting to reach London. Their presence alone guarantees the city’s safety, no matter who is in charge of its defense.”

They rode in silence for a little, then she said, “And are you so certain that there will be an attack? The Danes did not come last summer. Mayhap they will stay away again.”

“We can hope for that,” he said, “but by now they will know that our fleet has been destroyed.” He shook his head, wishing that he could be more sanguine. “They will come, and soon. There is nothing we can do now to stop them. People are afraid, and the king most of all.”

“But not to London,” she said softly, “because of the fleet anchored here. Where then?”

He frowned, for he had been trying to puzzle that out himself for days.

“Sandwich again, perhaps. The town and its walls have been completely rebuilt since Tostig’s army burned it three years ago, but it is not an easy place to defend. The Sussex coast is vulnerable as well, because when Wulfnoth fled he took a great many of the Sussex defenders with him.”

“What of the regions north of London? Is it possible they may strike the fen country?”

“No place is completely safe,” he said, then looked hard at her. “What is your interest in the fens?”

She frowned into the distance, as if she could see some invisible threat there.

“The king has sent Edward to the abbey at Ely for schooling,” she said.

“Ah,” he breathed. “I did not know.” He should have guessed that it had to do with the boy, that Edward was not in London, else he would have been at Emma’s side even now.

“There are many tempting treasures at Ely,” she said, “and a king’s son would not be the least of them if he should be discovered there.”

“Perhaps so, but the abbey is protected somewhat by the fens themselves. There are watchers on the coast, and the monks would have adequate warning of an attack that would allow them to flee. Edward is well guarded, is he not?” He knew almost nothing of his half brother, and that was intentional. The child was a maddening reminder of his father’s claim to Emma’s body.

“He has his own retinue, yes.”

“I expect they will keep Edward safe, and that you need not fear for him.” He meant to reassure her, but when he glanced again at her ripening figure, a sudden, hot streak of bitterness knifed through him. “There will be another child in his place soon, I see.”

For a heartbeat, then two, she made no reply, but he saw her face harden and her mouth settle into a thin line. Even before she spoke, he knew that he had blundered.

“One child can never take the place of another, my lord,” she rebuked him, her voice cold as steel.

He cursed under his breath. He had spoken from despair and jealousy; had not considered how his words could be willfully misinterpreted by a mother who has just been parted from her only child. Snatching the bridle of her horse, he brought both mounts to a halt.

“You know that is not what I meant,” he said. “Do not purposely misunderstand me, Emma, I beg you. If you wish me to keep my distance while I am in London, you must say so. But do not invent reasons to push me away.”

• • •

Emma gazed into piercing blue eyes that regarded her with an emotion she hardly dared name. It had been many months since she had studied his face, and now she noted the changes that time and events had wrought there. He had watched two of his brothers die, had been through battle and seen men butchered all about him. It seemed to her that he looked older than his years, and that he had already shouldered some of the cares that would come with the burden of a crown.

She was aware that in the distance, back along the road toward London, her retinue had come to a halt, leaving her sequestered, for courtesy, with the son of the king. She could speak plainly to him here, overheard by no one. But what was she to say? Was she to speak of his grief at the loss of his brothers? Of her bitterness toward the king and her fear for her son? Was she to tell him of her desperate need for someone to talk with and confide in?

No. She could say none of those things, and perhaps he was right. Perhaps she was inventing reasons to push him away, for almost as strong as her fear for Edward was her fear of the power that Athelstan would have over her, should she allow him to take it.

She drew in a breath and said, “I am a reviled queen, my lord. I have neither the strength nor the will to push away a

friend

.”

She placed such emphasis on the last word that he could not miss her implication.

The blue eyes flashed, searching her face as if he would read all that was in her mind. At last he spoke in a voice raw with passion.

“I will never be anything less than your friend, Emma,” he said, “and I would be far more than that, if you would but let me.”

His words hung in the air between them, potent as wine, dangerous as a naked blade. She dared not give him the response that he so clearly wanted, for along that road disaster waited for both of them. Desperate to step away from what she feared was an abyss she said, “Be my protector, then, and my adviser, for I have great need of both.”

For a moment he said nothing, and then the dangerous light in his eyes was quenched.

“As you wish, my lady,” he said, his tone curt.

He released her bridle and they resumed their progress toward the West Minster, in what she felt was a brittle and stony silence. When she could bear it no longer, for she had great need of his counsel, she said, “My lord, I believe we have a mutual enemy in Lord Eadric. It would be helpful to me to learn what you know of him. Many in London now call him the Grasper. Do you know of this?”

“I have heard it, yes,” he replied, “and the name is more than apt. He is using his position as ealdorman to enrich himself at the expense of those whom he should protect.”

To her relief he seemed to have shrugged off his ill humor, and now he continued in the same thoughtful tone that had marked their earlier conversation.

“My father places too much trust in the Mercian ealdorman, and I would to God I knew how to wean the one from the other. But Eadric has my sister Edyth in thrall, as I am sure you know. If the king is not listening to Eadric, he is listening to Edyth, and what one says the other repeats like a litany.” He grimaced. “I suspect that Eadric was behind the accusations made against Wulfnoth at Sandwich.”