The Prince, the Cook and the Cunning King (4 page)

When I got home to Wales I’d make sure servants had a better life than this.

On the fourth day I struggled to carry a leather bucket of water from the well in the yard.

Fat Cook told me to hurry and swung his boot at my backside. I stumbled and spilled the water.

“Stupid girl,” he snarled. “You’ll have to do it all over again!”

I sighed, picked up the empty bucket and trudged back to the well. Lambert helped me carry it back to the door.

“He’s a bully,” Lambert said.

“Then I’ll have to teach him a lesson,” I snapped.

Lambert stopped and looked at me carefully. “You’re a kitchen maid–what can you do?”

I almost blurted, “The King is my uncle and I can have Cook executed with his own meat-axe!” but I had to keep my secret. I still had to fool Lambert into telling me the truth. I said, “There is some yellow-dock plant in the pantry, isn’t there?”

Lambert nodded.

“Can we get some?”

“It’s locked by Cook,” he said, “but I can open locked doors.”

I grinned. “How did you learn that?”

“My father made organs in Oxford and I helped with the locks on the lid. I know all about them.”

I stopped in the freezing yard. “I thought your father was the Duke of Clarence and you were the true king?”

Lambert laughed. “That’s right. But I was switched when I was a baby to save me from being done away with. The organ-maker’s son was brought up as Edward … and I was brought up as the organ-maker’s son! I still think of him as my father. The rebels knew that–but they died in battle.”

“But does Unc–er … King Henry know that?”

“No! If he did he’d execute me. I’m a bit simple–but I’m not mad. Of course, no one knows the truth,” he laughed.

“Except me,” I said.

“Except you–and you’re not going to tell the King, are you?”

The kitchen was quiet. The servants watched us, open-mouthed.

Cook had locked himself in the pantry for lunch. I put my ear to the door and heard him snore. I stood aside and let Lambert work on the lock with a knife. In a few moments it clicked open.

The leather hinge creaked. I peered round the door. Cook snored on. His wine sat on the bench beside him.

The pantry was full of cooked meats and pastries, cheeses and bread, wine, honey and herbs. It was like a treasure chest. I passed a large cheese out to the servants and they hurried to a corner to carve it and eat it before Cook woke up.

The stone jar of yellow-dock leaves scraped as I lifted it from the shelf. Cook stirred. He snorted. He belched. He smiled in his sleep.

I rubbed the leaves between my hands and let the powder fall into his wine cup.

Lambert gasped. “But …”

“Shhhh!”

I put more powder in the cup.

“But he’ll …”

“Shhhh!”

I put the empty jar back on the shelf. We crept out and Lambert locked the door.

We waited.

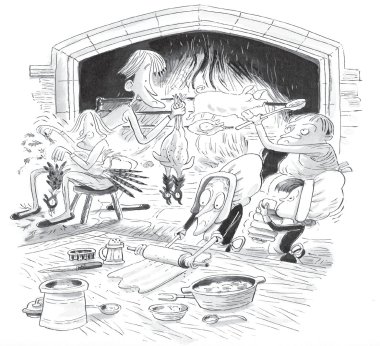

An hour later, Cook came out, red-faced and shouting orders. We scuttled around the kitchen like the rats in my hayloft, making dinner for the royal family and their guests.

King Henry was mean with his money, but he always put on a good feast when he had guests. We baked a fish pie, roasted pheasants and a baby pig, boiled dishes of peas and made cups of rose-flavoured custard. Six o’clock chimed. Dinner was ready to serve.

Cook clutched his fat gut–that was the yellow-dock powder starting to work.

Lambert chewed a knuckle nervously. “Yellow-dock makes you run to the jakes,” he whimpered.