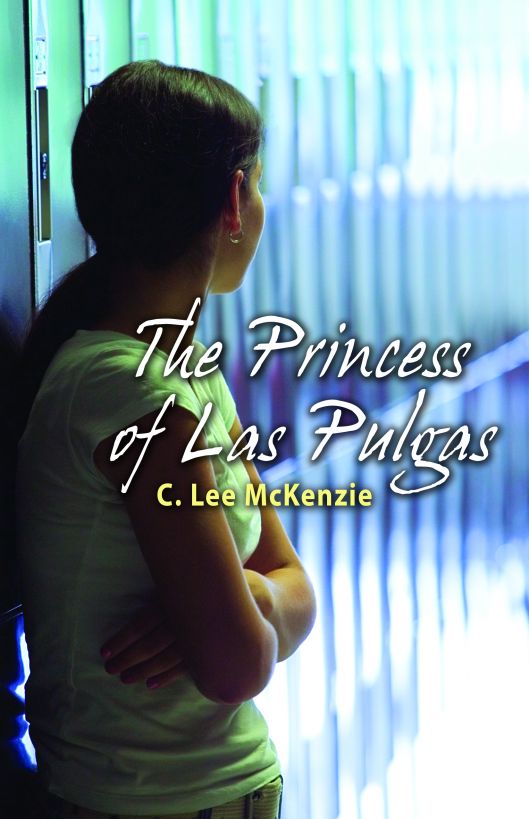

The Princess of Las Pulgas

Read The Princess of Las Pulgas Online

Authors: C. Lee McKenzie

Tags: #love, #death, #grief, #multicultural hispanic lgbt family ya young adult contemporary

Table of Contents

"A beautifully written,

meaningful, young adult novel. Carlie Edmund will jump off the page

and pull you into a poignant and timely story of loss and ultimate

gain."

-Francisco X. Stork, author

of Marcelo in the Real World, a New York Times Notable Children's

Book of 2009, a Publishers Weekly Best Book of 2009, and a 2010

YALSA Top 10 Best Books for Young Adults.

The Princess of Las

Pulgas

C. Lee McKenzie

Published by C. Lee

McKenzie at Smashwords

Copyright 2013

Smashwords Edition, License

Notes

This ebook is licensed for

your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or

given away to other people. If you would like to share this book

with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each

recipient. If you're reading this book and did not purchase it, or

it was not purchased for your use only, then please return to

Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting

the hard work of this author.

Chapter 1

Last night I pleaded with

Death, but he turned a bony back to me, pushed Hope into the

corridor and shut the door.

Now we’re waiting, all of

us. Mom in the chair next to Dad’s bed, holding his hand as if she

can keep him with us as long as she doesn’t let go. Keith asleep on

the rollaway a nurse wheeled in earlier. He’s on his side, his long

runners’ legs drawn to his chest and his head resting on his arm.

Me, scrunched down into a chair at the foot of Dad’s bed. I no

longer feel like I have a body. I’m not even tired, just numb. Then

Death. He’s backed into the darkest corner.

I twist my Sweet Sixteen

bracelet around and around, counting the tiny links. Mom and Dad

gave it to me in June before I learned how hospitals smelled at two

a.m. or how I preferred nightmares to being awake.

I hate being here.

I hate what's happening.

I want it over.

I close my eyes and let my

head fall back against the vinyl chair.

No. I don’t mean that.

Two a.m.: The hands of the

wall clock go around and around. Slow. Steady. Doling out the hours

one-second at a time.

Three: I must have slept,

but I don’t remember dozing and I still feel tired.

Three-ten: Something’s

different and the shift is as sudden as it is subtle—a missed tick

of a clock, an unexplained space in the air, a suspended drip over

a sink.

A steady and high-pitched

sound tentacles its way through the room. A flat line of green

streaks across the monitor and the darkest corner is suddenly

empty.

Keith sits up on the edge

of the rollaway, staring at the floor. Mom rests her head against

Dad’s still chest. Around me the room curls up at the edges like a

late autumn leaf and I’m sure everything will soon crumble into

tiny bits.

My dad was an important man

in Channing. His investment counseling business had survived

despite the economy, and all of his clients had names on doors with

President or Chairman of the Board stenciled beneath. Dad had held

just about every office on the city council and been financial

advisor to the mayor, so the memorial service is long with

speeches, and the church is crowded with VIPs.

Mom hired the caterer that

her best friend, Maureen Fogger, always uses, so white-jacketed

strangers armed with trays of perfect small food thread their way

among the black or gray clothed guests. Our home fills with a hum

of voices.

The mayor proposes a toast;

the arts commissioner proposes a toast; three board members of

Dad’s company propose toasts. By four, people who were silent and

sad-faced earlier are now talking a bit too loudly, smiling,

telling jokes. Maureen Fogger has one of Dad’s young partners

cornered. She’s leaning in a little too close. The guy’s face is

flushed and his eyes dart around the room. Nobody notices his

silent cry for help except me.

An hour ago Keith retreated

upstairs. Mom stationed herself in the chair by the fireplace like

a lonely planet, and the guests orbit her, taking her hand,

touching her shoulder. I haven’t seen her cry since that night at

the hospital, but I’ve heard her through her bedroom door. Now I

think her whole body must be filling with tears while she waits for

the reception to end and for everyone to leave.

Dad was always inviting

people home. “Come for dinner, for the weekend, for Labor Day,”

he’d say. He insisted on balloons and confetti for special

celebrations. Confetti still turns up in the carpet from last New

Year’s Eve. He had the barbeque ready hours before my end-of-year

beach parties started, hours before Mom had a chance to tell him

whether he was cooking hot dogs or hamburgers that year. We called

him our party animal. If Dad were here, he would be moving from

group to group, telling a joke, gently guiding Maureen away and

letting his young partner escape. Dad would have loved this

“party.”

I’m not in the mood to love

anything about what's happening, so as soon as possible I slip away

to hide in my room where Quicken is curled up on my pillow in a

tight purring ball. Even with the door closed, I'm not far enough

away to mask the chatter of people downstairs. I slide open the

window facing the beach, inviting the drum of ocean waves to enter.

Their steady rhythm has always rocked me when I was uneasy. Today,

the crashing waves are angry, not soothing.

Closing the window, I fall

across the bed with my arms spread wide. Quicken arches her back,

stretches, and then brushes back and forth along my side before

curling up against me. In seconds her purr rumbles deep in her

throat.

Disappearing inside my

head, imagining a happy ending saw me through those months of Dad’s

cancer, so I need for it to get me through tonight and tomorrow and

the next day.

“Carlie, love. This is tough, but you’ll be

just fine. I know it.”

Dad used to say that

whenever I’d bring him a crisis. Then he’d brush my cheek with his

fingers and kiss the tears.

I’m not so sure this time, Dad.

Chapter 2

This is first year since I

learned about Jack-O’-Lanterns that we don’t have one for

Halloween. Snaggle-toothed grins were Dad’s specialty. Mom turns

out the walkway lights at dusk. We don’t answer the door for the

goblins and witches.

Only one ghost is allowed

to enter here now.

Chapter 3

Mom’s friend, Maureen

Fogger, invites us for Thanksgiving dinner.

We go.

We eat.

We leave early.

I fall asleep to Mom’s

crying. It’s become as much a part of home as the sound of the

ocean outside our windows.

Chapter 4

I drive Keith to the

Christmas tree farm like Dad used to do. We saw down a six foot fir

and tie it onto the top of the car. At home we carry it as far as

the front door, look at each other and set it down in front of the

bay window.

That’s where it

stays.

Chapter 5

Mom goes to Maureen

Fogger’s New Year’s Eve fundraiser. I think Keith’s at Mitch’s

house. I cancel babysitting for the Franklins and stay home. It’s

just the TV and me with Quicken curled on my lap,

purring.

Chapter 6

“Ten. Nine. Eight.” The

drum of Time Square voices beat out the final seconds of the year.

As the ball plunges to the count of one, paper bits flurry across

the TV screen—a sudden end and a sudden beginning. I choke back

tears at that thought—the one I’ve had since I watched my Dad

die—the moment when the world grew one breath smaller.

When I switch off the

television the house goes silent. Tonight’s the first time since

the memorial service that I’ve been here after dark without Mom or

Keith someplace close by, and now loneliness crowds the

room.

I twist my Sweet Sixteen

bracelet around and around, fingering the tiny links.

Setting Quicken down I

stretch up from the couch. “Come on fur person.”

Leaving on a few downstairs

lights for Mom and Keith, I pad up the steps behind my cat. She

leaps to her cushion at the foot of my bed and curls into a tight

circle.

I wish I could fall into a

steady purring sleep like she does. I wish Mom would come home. I

even wish Keith would shuffle down the hall to his mole hole of a

room.

On my desk my journal lies

open to the almost blank sheet of paper with a date across the top.

I trace my finger over “October 22.” The rest of the page is

blotched with old tears.

Perhaps because I can’t

stand to read about the darkness inside me, I’ve avoided writing

anything since that day. I feel like I’m wrapped in a

cocoon.

“Carlie love, you’ve been shut away long

enough. It’s time to rejoin your world.”

My dad’s talking to me like

he used to, only now his words come like whispers inside my

heart.

The journal was his idea.

After I won Channing’s Scribe contest my freshman year, he handed

me a small package. Inside was this blank book embossed with C. E.

On the inside cover he’d written. “For Carlie Edmund, one girl who

has the imagination to write wonderful stories. Put some of those

ideas down and use them later when you need them.”

Since October 22nd, there's

nothing this One Girl has to write that anyone would want to read,

especially me.

“You have all kinds of good ideas, Carlie

love.”

“I only have one idea and it’s so not a good

one.”

“Good or bad you have to start

sometime.”

I turn to a blank page and

take up my pen. “Sometimes bad things happen . . . even in

Channing.”

The first bad thing that

springs into my head is spelled c-a-n-c-e-r, then comes the vision

of that hospital room, the hours plodding forward. More memories

creep forward like tiny monsters and sit hunched, waiting for me to

notice them.

I drop my pen onto the

journal page, tasting rather than hearing the low sound just behind

my lips, not quite a cry, not quite a moan, just something

sharp-edged, something I’d like to keep hidden.

When I read what I just

wrote, some letters aren’t clear. Even though I’ve turned to a new

page, the tears have made the surface rough, so October 22nd has

bled through to a new day.

What can I write that won’t

tear at me every time I read it? What can I write that won’t crush

my heart and send me back to that day life changed?

The

answer—

nothing

.

“I’m sorry, Dad,” I say

softly, then I listen to the silence. I don’t know what’s worse,

when he talks to me or when he doesn’t.

From outside comes the

sound of a car pulling into the driveway, then the garage door

slides open. Mom’s home.

I change into my pajamas

and robe, brush my hair and pull it into a long dark tail that

hangs to my shoulders. I got the thick black mane from my mom’s

side of the family. Keith inherited Dad’s sandy color and the

spatter of freckles across his cheeks. We don’t look like we’re

related, except for our eyes and those are all Dad, sand pebble

gray.

Mom will make cocoa before

she goes to bed just like she did when Dad was here. Cocoa is still

a bedtime ritual, but it’s not the happy one it used to be. Now she

sits alone at the table, studying real estate books, or, as she

says, “sorting out the finances.” After being by myself most of the

night I need company, so cocoa and Mom to talk to sound

good.

“Hi Mom. How did the

fundraiser go?” She’s already pouring milk into a saucepan when I

slipper my way into the kitchen.

“Let’s see.” She sets the

saucepan on the cooktop, and stirs in cocoa. “I made a hundred plus

a fifty dollar bonus from the caterer at Maureen Fogger’s annual

charity event—proceeds going to Bangladesh or Milwaukee, depending

on which place needs it more this year.”