The Psychopath Inside (11 page)

Read The Psychopath Inside Online

Authors: James Fallon

But we got the data we needed for the show. Using an interpreter, I interviewed people in each tribe while James collected

vials of spit and put them on ice for later genetic testing. These nomadic people couldn't remember any murders, going back at least four generations, so we hypothesized they would have a low incidence of the warrior gene because it wouldn't be very helpful for them in their peaceful communities. Among Caucasians, about 30 percent of X chromosomes have the high-risk MAOA allele. That rate is much higher in Africans and Chinese, and in the Maori. These racial differences have been controversial, and the tribes took a chance with us. What if it turned out that the Arab groupâthe Bedouinsâhad a higher concentration? We predicted that rates in both groups would be lower than 30 percent.

We were wrongârates were about 30 percent, just as high as in Europeans and North Americans. It appeared that the environment might be playing a bigger role than I'd anticipated. In the harsh conditions of the desert, you need to cooperate to survive. If you're violent you could be ostracized, and then you're on your own and you might die. So in this case it was enculturation rather than genetics that was constraining people's aggression. Nurture rather than nature. Another small hit to my belief that DNA explains 80 percent of what we do.

In 2011, I was back on the road discussing psychopathy, violence, abuse, dictatorships, and . . . my own brain, and I started to understand why prior to college I had been so seemingly moral and well behaved and after that had become a different person.

What seems to have happened to my brain at puberty when I developed OCD, and then experienced hyper-religiosity and

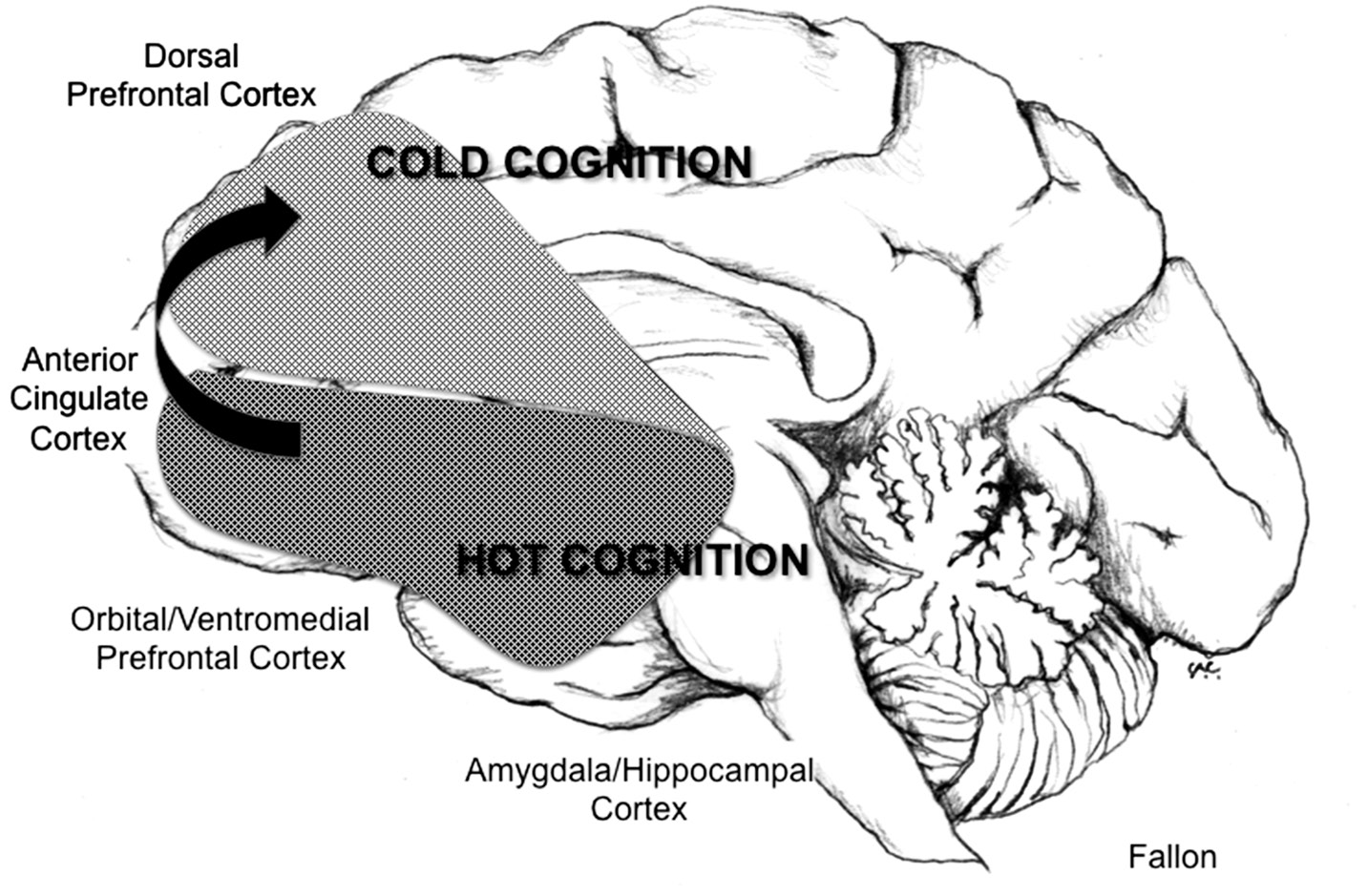

eccentric ideations, was overactivity in the ventral stream circuitry of my prefrontal cortex. My obsessions with ethics and morality and my hyper-focused attention are indicative of an overfunctioning orbital and ventromedial prefrontal cortex. It is normal for prepubertal children to be very aware of ethics, morality, and fairness. But as a child enters adolescence the dorsal stream circuitry of the prefrontal system starts to mature more and more, and thus the emotionality and hyper-morality of some children gets dampened by the dorsal stream, which processes cold logic, reasoning, planning, and the practical functions of life. This switching from the ventral to dorsal stream circuitry should balance one's hot, emotional, moral-based thinking and feeling to more mature logical reasoning by the end of adolescence. By twenty-five years of age, give or take several years, this balance of emotion and reason should finally mature.

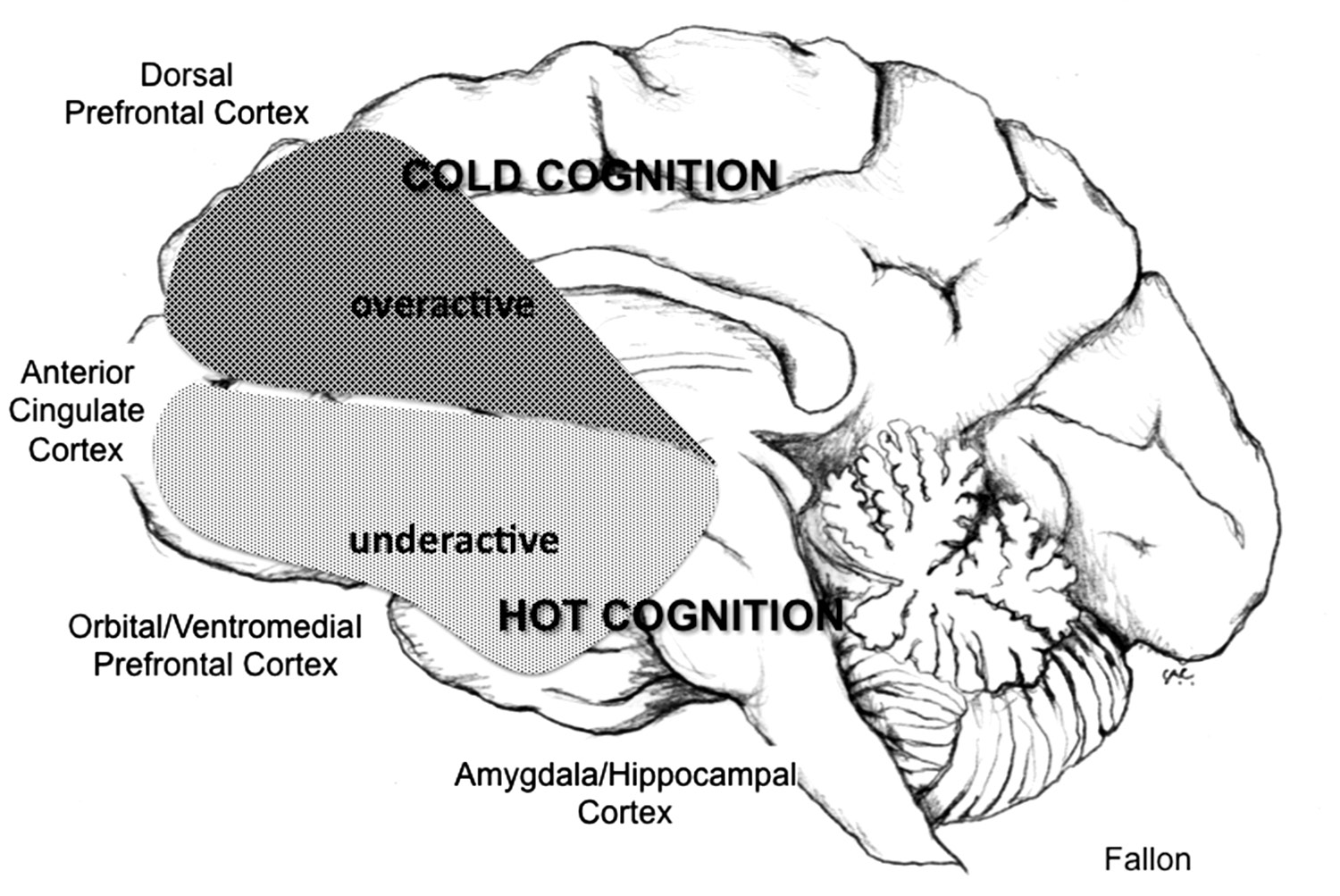

I think that in my case, when the normal switching “upward” toward the dorsal prefrontal stream should have occurred in my late teens, it did switch up, but then my ventral system turned off, and my prefrontal cortex stayed in the “up” position for the rest of my life, greatly favoring my cold cognitive skills at the expense of my ventral emotional, moral functioning. And it never balanced out like it should have when I was in my twenties. And while all of those dorsal stream cold cognitive functions thrived, they appear to have done so at the expense of the ventral circuitry. So I continued to be social, but I lacked the interpersonal skills and empathy of most others (a subject we'll return to in the next chapter).

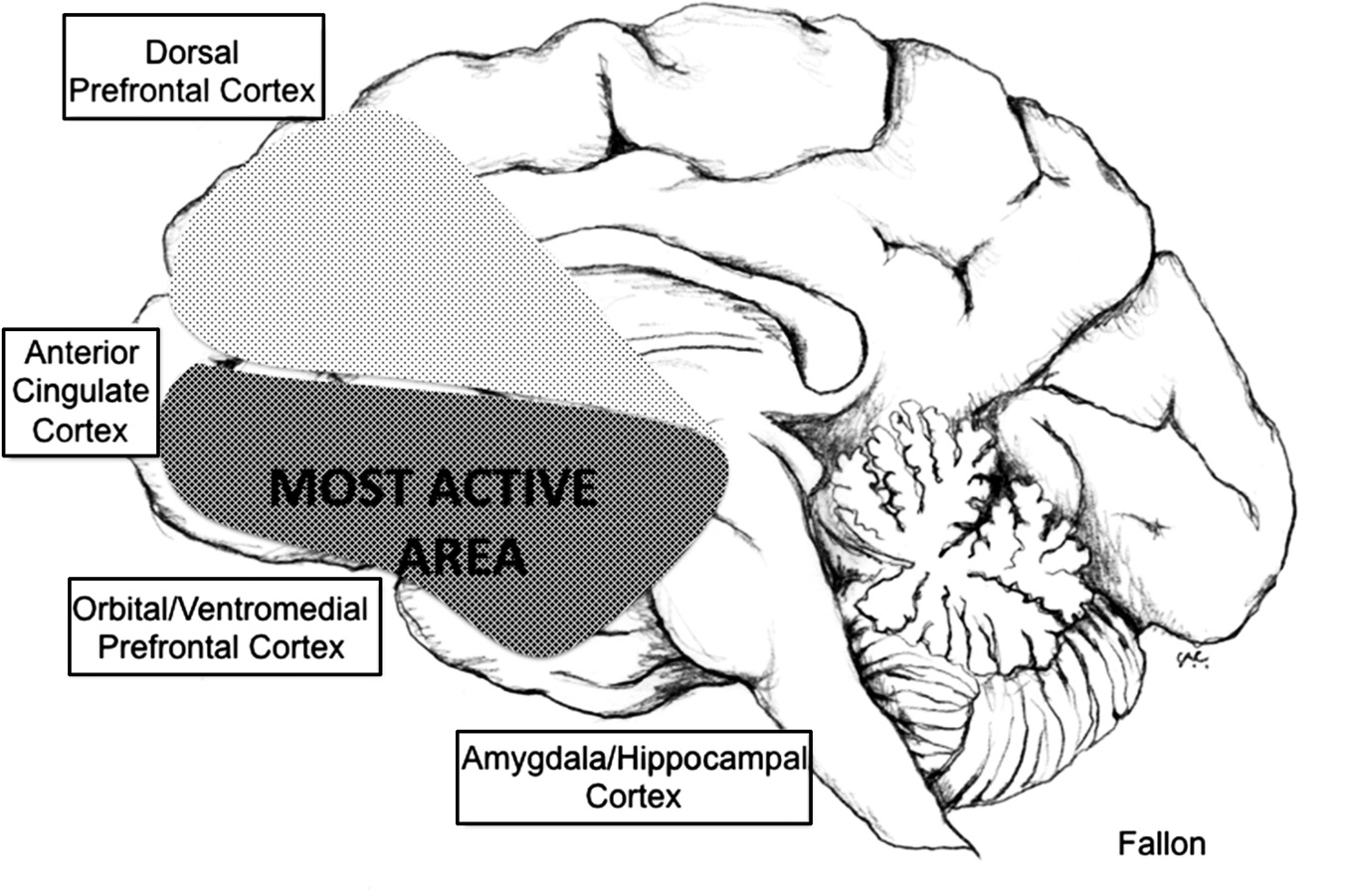

FIGURE 6A:

The immature prefrontal system. Normal activity of the prefrontal cortex in a prepubescent child, showing high maturity and activity in the ventral stream circuitry (in dark gray) and low maturity and activity in the dorsal stream circuitry (light gray).

What probably happened in my brain was that around the time of puberty and my early teen years, my ventral prefrontal cortex was more active than normally present at that age, leading to obsessions, hyper-religiosity, and hyper-focused attention, which I did display during that stretch of development. Then, in later adolescence, when the switch should have increased dorsal circuitry and decreased ventral circuitry, leading to a frontal lobe in dynamic balance, something else occurred. The balancing of the dorsal and ventral systems did not occur, perhaps because of a faulty switch in the anterior cingulate cortex. At that point in my late teens, my ventral system may have shut down too much, and the dorsal system may have then overfunctioned. Behaviorally, this may have resulted in my acute executive traits and flattened emotional sensibilities.

FIGURE 6B:

The maturing (and switching) teenage prefrontal system. Normal maturation of the prefrontal cortex system in early and middle adolescence, with maturing dorsal stream circuitry and associated cold cognition.

Note in figure 6E a picture of my adult PET scan showing this unbalanced state in my frontal lobe. This may explain why I have feelings that are muted and lead me to base my relationships more on cold cognition and fairness much more than a normal person would.

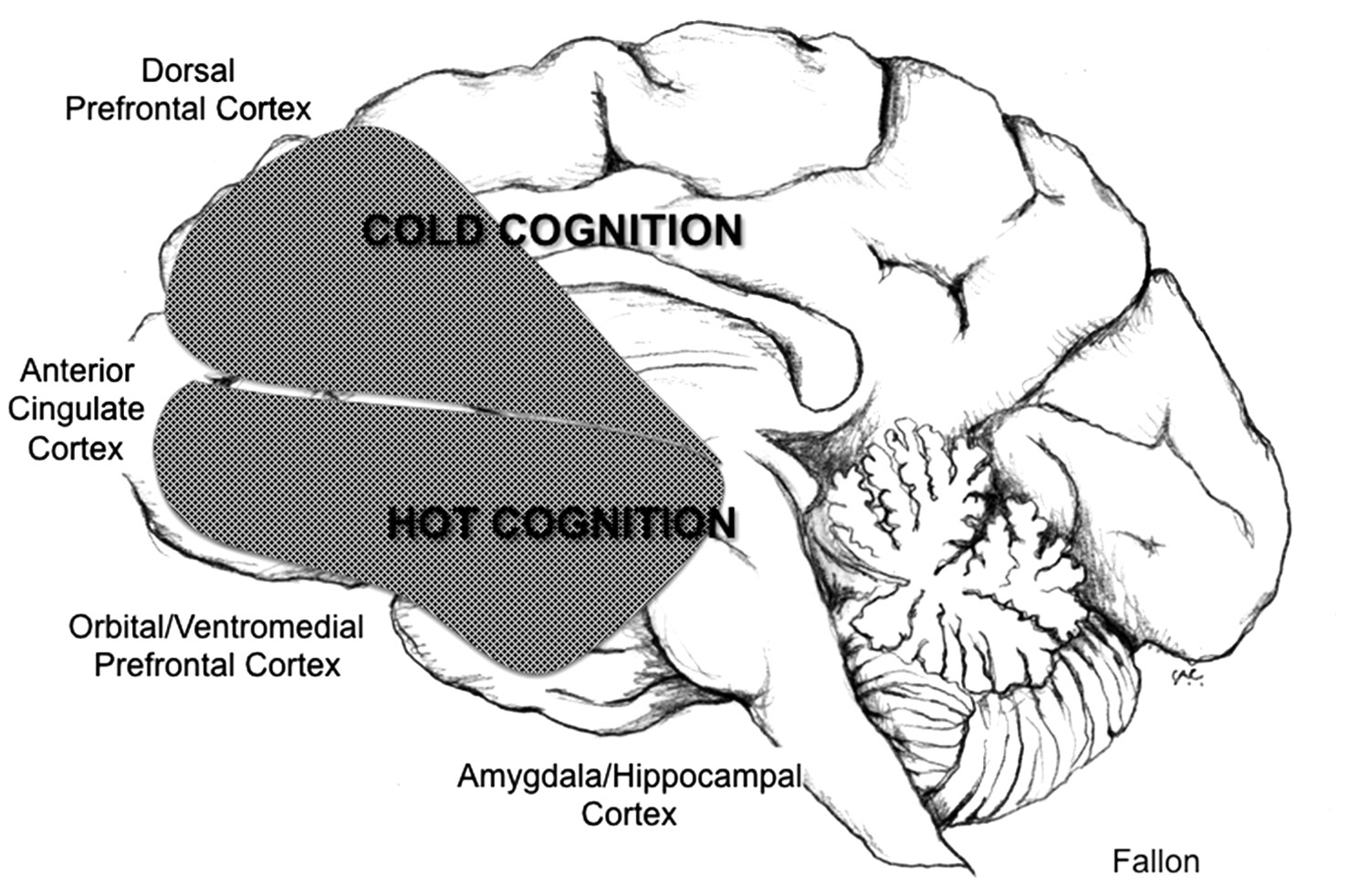

FIGURE 6C:

The mature adult prefrontal system in balance. Normal maturation of the prefrontal system in late adolescence and early adulthood, showing a balance of ventral and dorsal circuitry.

FIGURE 6D:

The overcompensated adult prefrontal system. Out of balance after switching from ventral to balanced ventral/dorsal prefrontal system.

So if my dorsal system, responsible for cold cognition and planning, became so dominant halfway through college, why was

that the time I became a wild man? Well, I'd always been a class clown and kind of a pleasure seeker. But I'd held myself back, knowing I had an addictive personality. Now, with confidence in my dorsal system's ability to manage my responsibilities, I knew I could party and still get stuff done. And I didn't have my orbital and ventral morality systems to inhibit me.

FIGURE 6E:

My PET scan.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

In early 2013, I came to understand another aspect of my brain. In the Rubik's Cube model, I discussed the different brain circuits thought to form the anatomical basis of behaviors, from attention

to memory, language, emotion, and morality. While no one has yet provided the insight to explain how neurons lead to our experience of conscious thought and feelingsâthe philosophical problem of consciousnessâthe circuit view of the brain provides some explanations of cognition and can organize data we see in genetics, neuropharmacology, and structural and functional brain scanning.

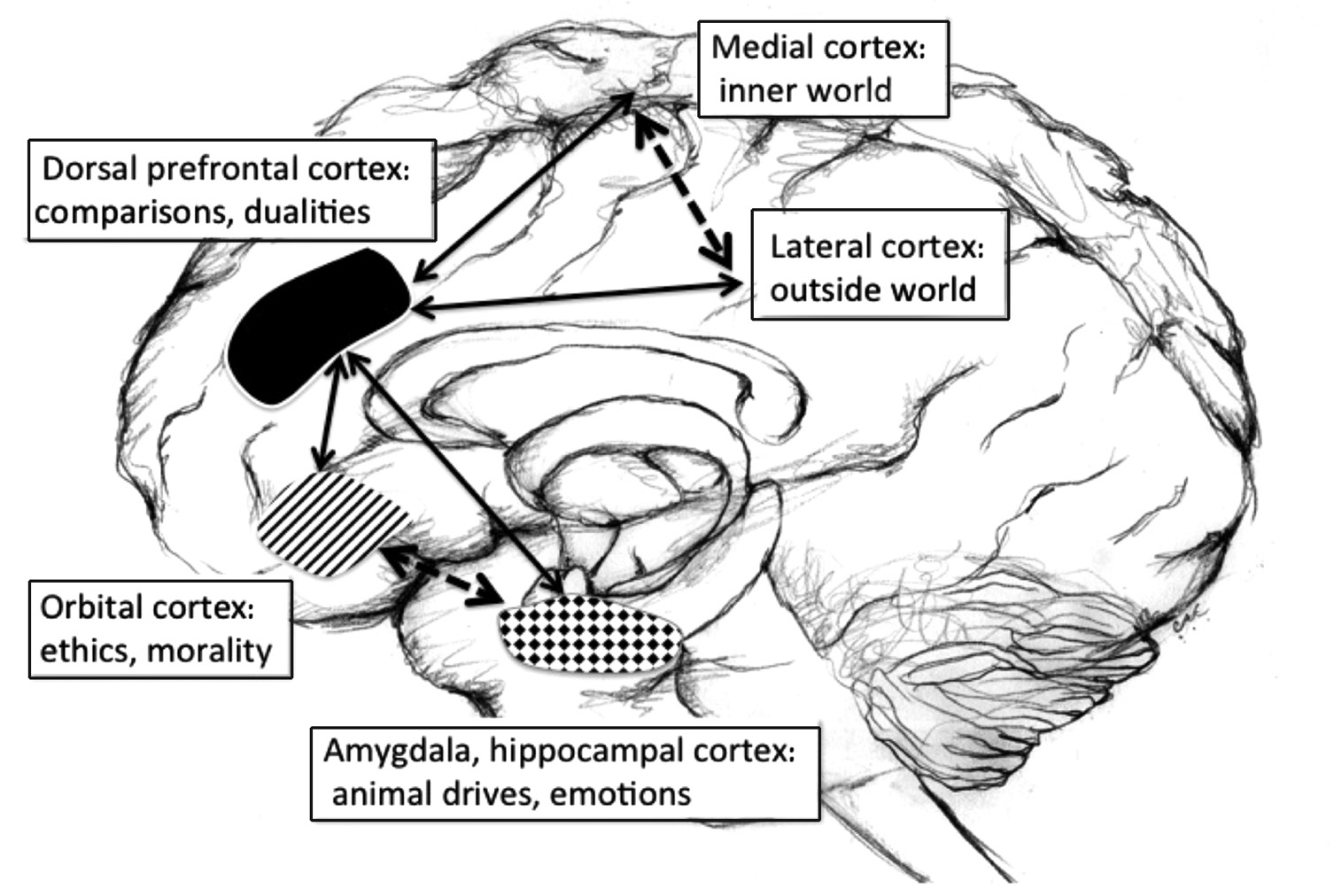

One recurring feature we can measure in different functional circuits is that for every general function, like perception or emotionality, there appear to be two competing or mutually inhibitory circuits in play. In this book I have focused on the competing interplay between the limbic areas like the amygdala that mediate basic drives such as fear, anxiety, aggression, and pleasure, and the orbital/ventromedial prefrontal cortices that mediate inhibition of these amygdaloid drives, and at the highest level appear to subserve behaviors related to ethics and morality.

In the diagram of the brain shown in figure 6F, the orbital/ventromedial cortex is shown in diagonal hatching, and the amygdaloid cortices are represented as a mosaic of black diamonds. These two areas are directly connected to each other and inhibit each other, as shown by the dashed arrow. Part of the output of both areas is sent “downstream” to the basal ganglia motor areas and serotonin and dopamine cells in the brain stem (not illustrated), but part is sent to the dorsal prefrontal cortex, shown in black. While no one understands exactly how this happens, somehow the dorsal prefrontal cortex, critical for conscious thinking, is able to compare the two outputs and help render a conscious

“decision” of how one should act, or not act, in that particular moment. It compares the emotional and animal drives originating in the amygdala circuitry with the social and ethical context originating in the orbital/ventromedial cortical circuit. The connecting strips of limbic cortex aid in this process by adding the important human element of empathy.

Another way to look at this, in psychoanalytical language, is that the ego (dorsal prefrontal cortex) adjudicates the conflict between id drives (amygdala) and the moral context of the superego (orbital/ventromedial cortex). Onto this reductionist view of the brain as a machine, we might say that the dorsal prefrontal cortex

“sees” the dualistic nature of the conflict between drives and social context, and makes a decision.

FIGURE 6F:

Dualities perceived by the dorsal prefrontal cortex.