The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry (10 page)

Read The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry Online

Authors: Jon Ronson

Tags: #Social Scientists & Psychologists, #Psychopathology, #Sociology, #Psychology, #Popular Culture.; Bisacsh, #Social Science, #Popular Culture, #Psychopaths, #General, #Mental Illness, #Biography & Autobiography, #Social Psychology, #History.; Bisacsh, #History

“Tell Katy what things happen in your crotch,” Bindrim ordered her. Katy was Lorna’s vagina. “Say, ‘Katy, this is where I shit, fuck, piss and masturbate.’ ”

There was an embarrassed silence.

“I think Katy already

knows

that,” Lorna eventually replied.

knows

that,” Lorna eventually replied.

Many travelers around the California human potential movement considered nude psychotherapy to be a step too far, but Elliott, on his odyssey, found the idea exhilarating.

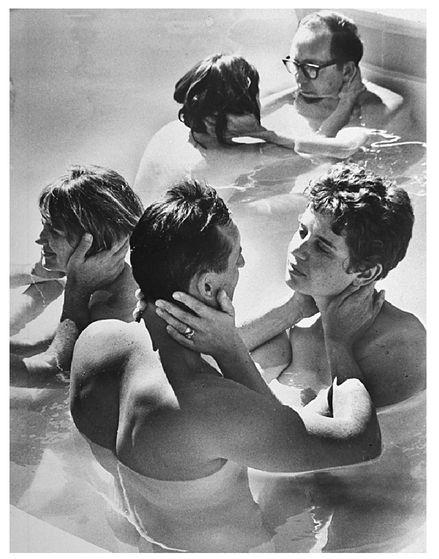

A Paul Bindrim nude psychotherapy session, photographed by Ralph Crane on December 1, 1968.

Elliott’s odyssey took him onward, to Turkey and Greece and West Berlin and East Berlin and Japan and Korea and Hong Kong. His most inspiring day occurred in London when (he told me by e-mail) he “met with [the legendary radical psychiatrists] R. D. Laing and D. G. Cooper and visited Kingsley Hall, their therapeutic community for schizophrenics.”

As it happened, R. D. Laing’s son Adrian runs a law firm just a few streets away from my home in North London. And so—in my quest to understand Elliott’s influences—I called in to ask if he’d tell me something about Kingsley Hall.

Adrian Laing is a slight, trim man. He has the face of his father but on a less daunting body.

“The point about Kingsley Hall,” he said, “was that people could go there and work through their madness. My father believed that if you allowed madness to take its natural course without intervention—without lobotomies and drugs and straitjackets and all the awful things they were doing at the time in mental hospitals—it would burn itself out, like an LSD trip working its way through the system.”

“What kind of thing might Elliott Barker have seen on his visit to Kingsley Hall?” I asked.

“Some rooms were, you know, beguilingly draped in Indian silks,” Adrian said. “Schizophrenics like Ian Spurling—who eventually became Freddie Mercury’s costume designer—would dance and sing and paint and recite poetry and rub shoulders with visiting freethinking celebrities like Timothy Leary and Sean Connery.” Adrian paused. “And then there were other, less beguiling rooms, like Mary Barnes’s shit room down in the basement.”

“Mary Barnes’s shit room?” I asked. “You mean like the worst room in the house?”

“I was seven when I first visited Kingsley Hall,” Adrian said. “My father said to me, ‘There’s a very special person down in the basement who wants to meet you.’ So I went down there and the first thing I said was, ‘What’s that smell of shit?’”

The smell of shit was—Adrian told me—coming from a chronic schizophrenic by the name of Mary Barnes. She represented a conflict at Kingsley Hall. Laing held madness in great esteem. He believed the insane possessed a special knowledge—only they understood the true madness that permeated society. But Mary Barnes, down in the basement, hated being mad. It was agony for her, and she desperately wanted to be normal.

Her needs won out. Laing and his fellow Kingsley Hall psychiatrists encouraged her to regress to the infantile state in the hope that she might grow up once again, but sane. The plan wasn’t going well. She was constantly naked, smearing herself and the walls in her own excreta, communicating only by squeals and refusing to eat unless someone fed her from a bottle.

“The smell of Mary Barnes’s shit was proving a real ideological problem,” Adrian said. “They used to have long discussions about it. Mary needed to be free to roll around in her own shit, but the smell of it would impinge upon other people’s freedom to smell fresh air. So they spent a lot of time trying to formulate a shit policy.”

“And what about your father?” I asked. “What was he like in the midst of all this?”

Adrian coughed. “Well,” he said, “the downside of having no barriers between doctors and patients was that everyone became a patient.”

There was a silence. “When I envisaged Kingsley Hall, I imagined everyone becoming a doctor,” I said. “I suppose I was feeling quite optimistic about humanity.”

“Nope,” Adrian said. “Everyone became a patient. Kingsley Hall was very wild. There was an unhealthy respect for madness there. The first thing my father did was lose himself completely, go crazy, because there was a part of him that

was

totally fucking mad. In his case, it was a drunken, wild madness.”

was

totally fucking mad. In his case, it was a drunken, wild madness.”

“That’s an incredibly depressing thought,” I said, “that if you’re in a room and at one end lies madness and at the other end lies sanity, it is human nature to veer towards the madness end.”

Adrian nodded. He said visitors like Elliott Barker would have been kept away from the darkest corners, like Mary Barnes’s shit room and his father’s drunken insanity, and instead steered toward the Indian silks and the delightful poetry evenings with Sean Connery in attendance.

“By the way,” I said, “did they ever manage to formulate a successful shit policy?”

“Yes,” Adrian said. “One of my dad’s colleagues said, ‘She wants to paint with her shit. Maybe we should give her

paints

.’ And it worked.”

paints

.’ And it worked.”

Mary Barnes eventually became a celebrated and widely exhibited artist. Her paintings were greatly admired in the 1960s and 1970s for illustrating the mad, colorful, painful, exuberant, complicated inner life of a schizophrenic.

“And it got rid of the smell of shit,” Adrian said.

Elliott Barker returned from London, his head a jumble of radical ideas garnered from his odyssey, and applied for work at a unit for psychopaths inside the Oak Ridge hospital for the criminally insane in Ontario. Impressed by the details of his great journey, the hospital board offered him a job.

The psychopaths he met during his first days at Oak Ridge were nothing like R. D. Laing’s schizophrenics. Although they were undoubtedly insane, you would never realize it. They

seemed

perfectly ordinary. This, Elliott deduced, was because they were burying their insanity deep beneath a façade of normality. If the madness could only, somehow, be brought to the surface, maybe it would work itself through and they could be reborn as empathetic human beings. The alternative was stark: unless their personalities could be radically altered, these young men were destined for a lifetime of incarceration.

seemed

perfectly ordinary. This, Elliott deduced, was because they were burying their insanity deep beneath a façade of normality. If the madness could only, somehow, be brought to the surface, maybe it would work itself through and they could be reborn as empathetic human beings. The alternative was stark: unless their personalities could be radically altered, these young men were destined for a lifetime of incarceration.

And so he successfully sought permission from the Canadian government to obtain a large batch of LSD from a government-sanctioned lab, Connaught Laboratories, University of Toronto. He handpicked a group of psychopaths (“They have been selected on the basis of verbal ability and most are relatively young and intelligent offenders between seventeen and twenty-five,” he explained in the October 1968 issue of the

Canadian Journal of Corrections

); led them into what he named the Total Encounter Capsule, a small room painted bright green; and asked them to remove their clothes. This was truly to be a radical milestone: the world’s first-ever marathon nude psychotherapy session for criminal psychopaths.

Canadian Journal of Corrections

); led them into what he named the Total Encounter Capsule, a small room painted bright green; and asked them to remove their clothes. This was truly to be a radical milestone: the world’s first-ever marathon nude psychotherapy session for criminal psychopaths.

Elliott’s raw, naked, LSD-fueled sessions lasted for epic eleven-day stretches. The psychopaths spent every waking moment journeying to their darkest corners in an attempt to get better. There were no distractions—no television, no clothes, no clocks, no calendars, only a perpetual discussion (at least one hundred hours every week) of their feelings. When they got hungry, they sucked food through straws that protruded through the walls. As during Paul Bindrim’s own nude psychotherapy sessions, the patients were encouraged to go to their rawest emotional places by screaming and clawing at the walls and confessing fantasies of forbidden sexual longing for one another even if they were, in the words of an internal Oak Ridge report of the time, “in a state of arousal while doing so.”

My guess is that this would have been a more enjoyable experience within the context of a Palm Springs resort hotel than a secure facility for psychopathic murderers.

Elliott himself was absent, watching it all from behind a one-way mirror. He would not be the one to treat the psychopaths. They would tear down the bourgeois constructs of traditional psychotherapy and be one another’s psychiatrists.

There were some inadvertently weird touches. For instance, visitors to the unit were an unavoidable inconvenience. There would be tour groups of local teenagers: a government initiative to demystify asylums. This caused Elliott a problem. How could he ensure the presence of strangers wouldn’t puncture the radical atmosphere he’d spent months creating? And then he had a brainwave. He acquired some particularly grisly crime-scene photographs of people who had committed suicide in gruesome ways, by shooting themselves in the face, for instance, and he hung them around the visitors’ necks. Now, everywhere the psychopaths looked they would be confronted by the dreadful reality of violence.

Elliott’s early reports were gloomy. The atmosphere inside the Capsule was tense. Psychopaths would stare angrily at one another. Days would go by when nobody would exchange a word. Some noncooperative prisoners especially resented being forced by their fellow psychopaths to attend a subprogram where they had to intensively discuss their reasons for not wanting to intensively discuss their feelings. Others took exception to being forced to wear little-girl-type dresses (a psychopath-devised punishment for noncooperation in the program). Plus, nobody liked glancing up and seeing some teenager peering curiously through the window at them with a giant crime-scene photograph dangling around his neck. The whole thing, for all the good intentions, looked doomed to failure.

I managed to track down one former Oak Ridge inmate who had been invited by Elliott to join the program. Nowadays Steve Smith runs a plexiglass business in Vancouver. He’s had a successful and ordinary life. But back in the late 1960s he was a teenage drifter, incarcerated for thirty days at Oak Ridge in the winter of 1968 after he was caught stealing a car while tripping on LSD.

“I remember Elliott Barker coming into my cell,” Steve told me. “He was charming, soothing. He put his arm around my shoulder. He called me Steve. It was the first time anyone had used my first name in there. He asked me if I thought I was mentally ill. I said I thought I wasn’t. ‘Well, I’ll tell you,’ he said, ‘I think you are a very slick psychopath. I want you to know that there are people just like you in here who have been locked up more than twenty years. But we have a program here that can help you get over your illness.’ So there I was, only eighteen at the time, I’d stolen a car so I wasn’t exactly the criminal of the century, locked in a padded room for eleven days with a bunch of psychopaths, the lot of us high on scopolamine [a type of hallucinogenic] and they were all staring at me.”

“What did they say to you?”

“That they were there to help me.”

“What’s your single most vivid memory of your days inside the program?” I asked.

“I went in and out of delirium,” Steve said. “One time, when I regained consciousness, I saw that they’d strapped me to Peter Woodcock.”

“Who’s Peter Woodcock?” I asked.

“Look him up on Wikipedia,” he said.

Peter Woodcock (born March 5, 1939) is a Canadian serial killer and child rapist who murdered three young children in Toronto, Canada, in 1956 and 1957 when he was still a teenager. Woodcock was apprehended in 1957, declared legally insane and placed in Oak Ridge, an Ontario psychiatric facility located in Penetanguishene.—FROM WIKIPEDIA

Other books

Teton Sunrise (Teton Romance Trilogy) by Henderson, Peggy L

Judith E French by Morgan's Woman

Binds by Rebecca Espinoza

Port of Errors by Steve V Cypert

Patriot (A Jack Sigler Continuum Novella) by Robinson, Jeremy, Holloway, J. Kent

A New Year Marriage Proposal (Harlequin Romance) by Kate Hardy

Tracks by Robyn Davidson

In the River Darkness by Marlene Röder

The Salvation of Vengeance (Wanted Men #2) by Nancy Haviland

The Happiness of Pursuit: What Neuroscience Can Teach Us About the Good Life by Edelman, Shimon