Read The Queen's Cipher Online

Authors: David Taylor

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #History & Criticism, #Movements & Periods, #Shakespeare, #Mystery; Thriller & Suspense, #Thrillers & Suspense, #Historical, #Criticism & Theory, #World Literature, #British, #Thrillers

The Queen's Cipher (24 page)

“Plagiarism and vanity: those were two of the vices Robert Greene accused him of in

Groats-Worth of Wit

. That said, dramatists are just like actors, mad as snakes and twice as bitchy.”

“Listen, love, if you were dying in a garret and a fellow playwright stole some of your best ideas and passed them off as his own, wouldn’t you get the hump?”

Sam bristled. Once again, his patronizing manner had got under her skin. He needed taking down a peg or two. “Oh yes, you’re very hot on plagiarism,” she sneered.

Freddie decided to ignore this barb. “You see what I’m driving at,” he said, his dark eyes blazing. “As late as 1620 Jonson is telling his Scottish friend Drummond that Shakespeare ‘wanted art’ and had a loose tongue. His opinion of Will only changes after that.”

“When did Bacon and Jonson get to be buddies?”

“Certainly by 1621 when Jonson attends Bacon’s sixtieth birthday bash and recites an ode he’d composed in which Bacon stands among his guests ‘as if some mystery thou didst!’”

“As if some mystery thou didst!” She repeated the line. “Is that a hint?”

“Oh yes, Ben is full of hints. There’s a big one in the Dedication. Part of it is a straight lift from the Dedicatory Epistle to Pliny’s

Natural History

!”

Sam did a double take. “What’s Pliny got to do with this?”

“You’ll see.” Freddie handed her photocopies of the two addresses. They both talked about country folk approaching their gods bearing gifts of milk and a leavened cake. One was a paraphrase of the other.

“And Jonson had read Pliny’s

Natural History

.”

“Of course he had,” Freddie replied. “There wasn’t a major Greek or Roman author he hadn’t read. You can track him everywhere in their snow, as Dryden once remarked.”

“You haven’t explained what Pliny is doing in the

Folio

Dedication.”

Freddie scowled at the open page. “I think it’s a kind of a signpost.”

Sam lit another cigarette. Adrenalin coursed through her veins, sharpening her senses. She began to perceive how a dazzling seventeenth-century intellect might think along such abstruse lines.

“Who replaced Pliny as the source of knowledge on natural history? Why, Francis Bacon of course. Bacon follows Pliny …” Her voice tailed off. “So what follows Pliny in the

Folio

Dedication?”

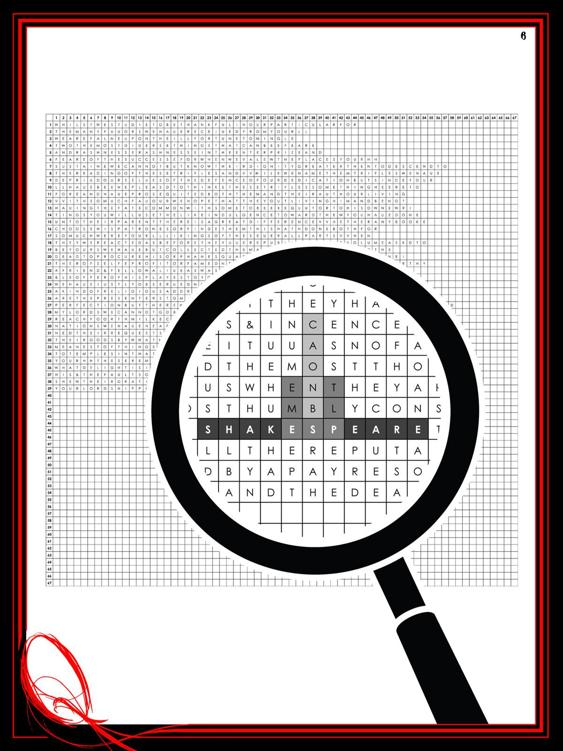

The next sentences in the inscription read, ‘And the most, though meanest of things are made more precious when they are dedicated to Temples. In that name therefore, we most humbly consecrate to your H.H these remains of your servant Shakespeare.’

Sam stared at the lines open-mouthed. “What’s wrong with that statement?” she asked.

He shrugged his shoulders.

“Temples are buildings, places of worship,

not

names,” she explained triumphantly. “We are being told that Shakespeare’s remains can be found in the name ‘temples.’ It’s a crossword clue!”

They were searching for a cryptogram.

The hours slipped by and they were no further forward. Glasses of wine gave way to cups of strong black coffee and the kitchen clock pointed to midnight. Lying between them was a sheet of graph paper on which they had faithfully reproduced all the letters of the

Folio

dedication. That was the easy bit. Finding a ‘temples’ cryptogram in a maze of letters was the problem, particularly when a temple could take so many shapes. It might be triangular, rectangular or even a double square.

Looking up, Freddie saw how tired and drawn she was. “We’re not getting anywhere,” he said.

But Sam wasn’t ready to give up. “We have to think like Ben Jonson. If he put a hidden message into the

First Folio

, how would he do it? He would know about cipher squares. They were in vogue in his day. But there would have to be a system of discovery.”

“How do you mean?” She had lost him again.

“Well, supposing we found a ‘temples’ figure in the squared text. Couldn’t it be there by accident? Of course it could. What’s needed is a mathematically precise route to the solution.”

“You mean some kind of geometric cipher key?”

“That’s right. The key could be in front of us or in an entirely different book …” She broke off as a thought occurred to her. “Hold on a moment! The cipher square in Selenus’ book is followed by a number alphabet which is called a

clavis

or key. What if Bacon’s

Alphabet of Nature

is the key we are looking for? After all, he told his friend Matthew to ‘put the alphabet in a frame’ and that letter is absolutely contemporaneous with the First Folio.”

“There’s a snag to that,” Freddie said. “The cipher system and the key have to be in use at the same time and the

Alphabet of Nature

didn’t appear in print until 1679. That’s fifty six years later.”

Sam’s smile took him by surprise. “Ben Jonson wouldn’t realize that when he was translating Bacon’s alphabet into Latin in 1622. He would expect the

Abecadarium Naturae

to be published alongside the

First Folio

. I say we give it a go.”

She tipped the contents of her shoulder bag onto the table, searching for the notebook in which she had jotted down the inquisition number counts.

| Inquisition | Greek and Latin Words | Number Count | Bacon Signature |

| 67 | | Francis | |

| Tau | 40 | ||

| Terra | 59 | ||

| 68 | |||

| Upsilon | 100 | Francis Bacon | |

| Aqua | 38 |

Later, when he tried to reconstruct this moment, he saw her lingering over these numbers before sitting bolt upright and moistening her lips with her tongue.

“It’s a Masonic cipher and it is geometric,” she said in a barely audible voice. “Do you remember what I said about the Triple Tau? How it was

Clavis ad Theosaurum

, the key to knowledge for Masons, and how in the House of the Temple adepts wear rings in which three T’s are set inside a triangle. Well, here in his opening inquisition, Bacon links the Triple Tau to the Earth and the Masonic symbol for the Earth is a Square. What we’re looking for in our cipher square is a triangle.”

Freddie felt conflicted; excited by her deduction and worried about its possible implications. He wondered how she knew what her head of department wore on his ring finger at Masonic meetings. It was, he feared, a quite intimate detail.

“How do we find this triangle?” he asked trying to sound calm.

Sam answered his question with one of her own. “Seeing Masonry is all about geometry, what are its basic symbols?”

He felt he was back at school. “The Square and the Compass,” he replied.

“Exactly, and the compass is a navigational instrument that measures directions. It goes together with the square. If the symbolism holds good these inquisition counts plot a course to our final destination, the triangular cryptogram.”

“Isn’t that a bit of a long shot?”

Sam didn’t think so. Lines of latitude and longitude had guided sailors for centuries. Bacon’s numbers were reference points, coordinate axes within the cipher square. Seeing he began with the Sixty Seventh Inquisition she thought the square should consist of sixty seven lines and columns.

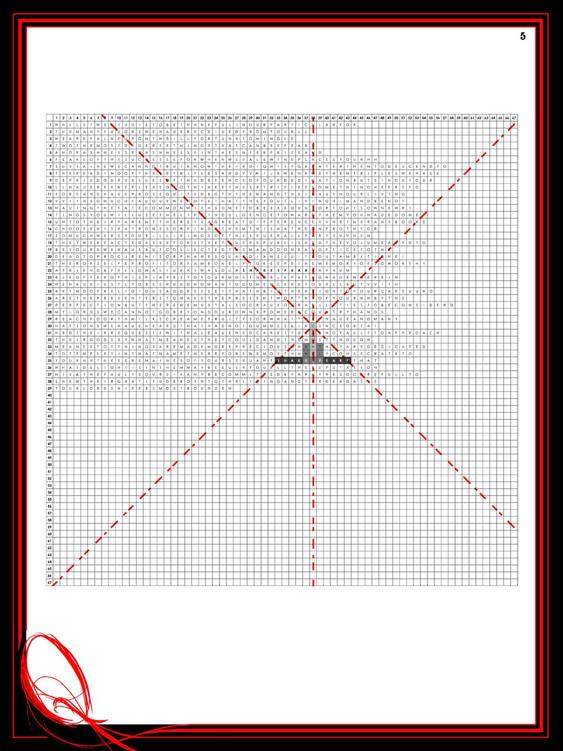

Freddie took the sheet of graph paper and turned it into such a square.

“Now let’s bring the other numbers of the Sixty Seventh Inquisition into play by constructing a tighter figure consisting of 40 lines and 59 column spaces.”

He used his ruler to create an inner rectangle on the graph paper. Made up of 39 lines, the longest of which had 58 letters, the

Folio

Dedication fitted snugly within these perimeters.

“So far so good,” she said. “These number counts act like a zoom lens. 67 is the wide-angle view and 59 and 40 alter the focal length. They suck you into the cipher square.”

Freddie nodded in agreement. “We’ve looked at line and column – now for the diagonals.”

Using a ruler and marker pen he drew lines across the cipher square. Starting from the bottom of the page, the 67th diagonal up right passed through the first letter in the name ‘Shakespeare’ while the 59th diagonal up left went through the last E. Moreover, these diagonals intersected one another in column 38 above the central S in Shakespeare’s name.

“Wow,” he gasped, “we’ve created a Shakespeare triangle!”

“Do you see what’s at the apex?” Sam could scarcely believe it.

The diagonals intersected in column 38 at the letter C. This gave them both of the number counts of the Sixty Eighth Inquisition – 100 and 38.

“We have Bacon’s personal seal, the letter C, at the apex of a Shakespeare triangle.

So where’s the word ‘temples.’ The most obvious place is inside the triangle.”

They peered at the graph paper. “I can see it,” he shouted. “There’s an anagram of ‘temples’ arranged in a U-shaped figure, like a shrine. It’s based on the central three letters of Shakespeare’s name. Above the E in column 37 you get EM and above the P in column 39 is LT. That gives us EEMSPLT or ‘temples.’

“What other words can be made out of those letters?” she wondered. “Can you think of any?”

“Well, for a start, there’s ‘stemple’ which is a kind of wooden crossbeam in a shelf but that word wasn’t around when the

Folio

was printed.”

“Here’s a better one – ‘pelmets.’”

“Did people have pelmets in the seventeenth century?” Freddie queried. He took the

Oxford English Dictionary

from its resting place behind the bread bin. “‘Pelmet, a valance, used to conceal curtain rods above a window or door.’ Earliest recorded usage – 1821! So we can forget about that!”

A cloud of dust flew into the air as he closed the dictionary.

“You are hurting me, Freddie.” He had seen something and was squeezing her hand so hard the blood had stopped flowing.

“Sorry, but this is bloody amazing. Look at the letters inside the ‘temples’ figure in the central column of the Shakespeare triangle – CAONB. Unscramble them and you’ve got Bacon!”

They had been told Shakespeare’s remains would be found in ‘temples’ and the cryptogram identified Bacon as the surviving member of the partnership when the Folio was published.

“Scholars will argue that Shakespeare’s remains are his literary works,” Sam warned.

Freddie reopened the Oxford English Dictionary. “According to the dictionary editors, the word ‘remains’ was first applied to a literary legacy in 1652 while the alternative definition of ‘a remaining part of something’ is of a much earlier origin.”

To steady her nerves, she lit another cigarette. “You do realise our academic colleagues will reject this out of hand. They’ll say an anagrammatic cipher is worthless.”

“I know they will. They’ll dismiss anagrams as word games.”

“Historically at least, they are wrong. Anagrams were taken so seriously in the early seventeenth century that forty books of Latin examples were published. I found that in Antonia Fraser’s book

The Weaker Vessel

.”

In teaching Gender Politics, Sam had learned a lot about anagrams in early modern Europe. Louis XIII of France had had his own court anagrammatist while, in England, Elizabeth’s courtiers vied with one another to make ‘some delectable transpose of her Majesty’s name,’ just as a later generation of sycophants saw in James Stuart ‘a just master.’ Anagrams also served a more serious purpose. Galileo and Newton used anagrammatic sentences to establish copyright while one of the

First Folio

dedicatees, the Earl of Montgomery, actually acknowledged his bastard son by christening him ‘Reebkomp,’ an anagram of Pembroke, the earldom he would never inherit.

“Of course anagrams sometimes happen by chance,” he added, choking on her cigarette smoke. “What are the odds against a ‘Bacon-in-temples’ cryptogram appearing by accident?”

Sam took the empty wine bottles and dropped them in the waste bin. “Maybe one in a million but statistics aren’t important. Geometry lies at the heart of this, the divine architecture of Solomon’s temple, the science passed to Pythagoras and adopted by the Masonic brotherhood.”