The Race to Save the Lord God Bird (22 page)

Read The Race to Save the Lord God Bird Online

Authors: Phillip Hoose

Chapter Thirteen.

Carpintero Real:

Between Science and Magic

Carpintero Real:

Between Science and Magic

Dr. James Van Remsen of Louisiana State University patiently explained the shift in taxonomic thinking about the Cuban and U.S. populations of the Ivory-bill.

Orlando H. Garrido and Arturo Kirkconnell's superb

Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba

(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000) reveals much about Cuba's natural history, as did a lecture I attended on May 29, 2002, at Harvard University by Giraldo Alayón.

Field Guide to the Birds of Cuba

(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2000) reveals much about Cuba's natural history, as did a lecture I attended on May 29, 2002, at Harvard University by Giraldo Alayón.

I visited Cuba three times between 2002 and 2004. Two interviews with Giraldo Alayón at his home in San Antonio de los Baños offered wonderful insights about the expeditions in Cuba and his personal involvement with the Ivory-billed Woodpecker there. One of the conversations also produced this chapter's opening quote, on p. 135. I was also able to interview Giraldo's wife, Aimé Posada, during the second of these two conversations. These talks were followed by several telephone conversations, a visit by Alayón to the United States, and dozens of e-mail exchanges. Quotes attributed to Alayón and Posada throughout chapter 13 came from these conversations and this correspondence. Alayón's recollections were supplemented by interviews with Cuban biologists Carlos Peña, Arturo Kirkconnell, Orlando Garrido, and Xiomara Gálvez Aguilera.

The account on page 141 of Alberto Estrada's glimpse of a big bird that he believed to be an Ivory-bill comes from the article “Of Woodpeckers and Frogs,” by Alberto R. Estrada. It appears on pp. 75â87 of

Islands and the Sea: Essays on Herpetological Exploration in the West Indies,

ed. Robert W. Henderson and Robert Powell,

Contributions to Herpetology

20 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles).

Islands and the Sea: Essays on Herpetological Exploration in the West Indies,

ed. Robert W. Henderson and Robert Powell,

Contributions to Herpetology

20 (Ithaca, N.Y.: Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles).

By telephone from his home in Kenya, Lester Short shared his memories of tracking the Cuban Ivory-bill. His observation that the Ivory-bills he saw in Cuba seemed “very wary” (p. 143) came from a telephone interview. Dr. Short also wrote two articles in

Natural History

magazine whose titles reflect the mood of the searches. The first is called “Last Chance for the Ivory-bill” (vol. 94, 1985). A year later, Short and his wife, Jennifer Horne, co-authored “The Ivory-bill Still Lives” (vol. 95, 1986).

Natural History

magazine whose titles reflect the mood of the searches. The first is called “Last Chance for the Ivory-bill” (vol. 94, 1985). A year later, Short and his wife, Jennifer Horne, co-authored “The Ivory-bill Still Lives” (vol. 95, 1986).

Any discussion of the Cuban Revolution is controversial, but I admire Christopher P. Baker's even-handed discussion in

Moon Handbooks: Cuba

(Emeryville, Calif.: Avalon Travel Publishing, 1999).

Moon Handbooks: Cuba

(Emeryville, Calif.: Avalon Travel Publishing, 1999).

The story in the sidebar on p. 139 about Orlando Garrido's stopping an international tennis match to collect an insect is legendary in Cuba. I heard it from several sources and was finally able to hear Garrido tell it himself in a telephone interview in Havana in March of 2003.

Information in the sidebar “Learning About Birds in Cuba” on p. 141 comes from my discussions with Cuban biologists and from an article, “Getting Things Done in Cuba,” by Steve Hendrix in

International Wildlife

magazine (January/February 2000). In this article I found the discussion of Orestes Martinez and his “Three Endemics” club presented in the same sidebar.

International Wildlife

magazine (January/February 2000). In this article I found the discussion of Orestes Martinez and his “Three Endemics” club presented in the same sidebar.

George R. Lamb reports his successful 1957 expedition in quest of the Cuban Ivory-bills in

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Cuba

(New York: Pan-American Section, International Committee for Bird Preservation, Research Report 1, 1957). John Dennis reports his 1948 quest in “A Last Remnant of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Cuba,”

The Auk,

vol. 65, no. 4 (October 1948).

The Ivory-billed Woodpecker in Cuba

(New York: Pan-American Section, International Committee for Bird Preservation, Research Report 1, 1957). John Dennis reports his 1948 quest in “A Last Remnant of Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Cuba,”

The Auk,

vol. 65, no. 4 (October 1948).

Chapter Fourteen. Return of the Ghost Bird?

Jane Goodall's quote at the chapter opening (p. 147) comes from her essay “My Three Reasons for Hope”; the full essay appears on the Web site of the Jane Goodall Institute (

www.janegoodall.org/jane/essay.html

).

www.janegoodall.org/jane/essay.html

).

The story of Jim Tanner's return to the Singer Tract (pp. 149â50) came from interviews and correspondence provided by Nancy Tanner. Most helpful was a newspaper article of March 25, 1986, entitled “Tanner Returns to the Tensas,” by staff writer Amy Ouchley of the

Madison Journal,

Tallulah, Louisiana. Tanner's list of Ivory-bill sightings is found in his file at Cornell (see sources for chapter 9).

Madison Journal,

Tallulah, Louisiana. Tanner's list of Ivory-bill sightings is found in his file at Cornell (see sources for chapter 9).

David Kulivan's purported sighting of the Ivory-bill, reported on pp. 150â51, and the subsequent dragnet for the birds in the Pearl River Wildlife Management Area have been described in hundreds of articles, magazine stories, and even books. Two of the best are Jonathan Rosen's “The Ghost Bird,” which appeared in the May 14, 2001,

New Yorker

magazine, and in Scott Weidensaul's book

The Ghost with Trembling Wings

(New York: North Point Press, 2002).

New Yorker

magazine, and in Scott Weidensaul's book

The Ghost with Trembling Wings

(New York: North Point Press, 2002).

Dr. James Van Remsen, the man who organized the six-person search for the Ivory-bill, allowed me to interview him several times during the height of the media frenzy, including once in his office in Baton Rouge (see quotes, p. 151, “He passed with flying colors,” and p. 155, “What about the

mites â¦

?”). Cornell University Lab of Ornithology maintained updated information throughout the search on its superb Web site,

www.birds.cornell.edu

. The search team's conclusions were reported in “The 30-day Zeiss search for the ivory-billed woodpecker ends,” Carl Zeiss Sports Optics news release, February 20, 2002.

mites â¦

?”). Cornell University Lab of Ornithology maintained updated information throughout the search on its superb Web site,

www.birds.cornell.edu

. The search team's conclusions were reported in “The 30-day Zeiss search for the ivory-billed woodpecker ends,” Carl Zeiss Sports Optics news release, February 20, 2002.

Epilogue. Hope, Hard Work, and a Crow Named Betty

Everyone should read or reread Rachel Carson's

Silent Spring

(New York: Ballantine Books, 1962). It's beautifully written and as timely now as it ever was.

Silent Spring

(New York: Ballantine Books, 1962). It's beautifully written and as timely now as it ever was.

A great source of information about the Piping Plover and the Peregrine Falcon is the Web site of NatureServe, the organization that keeps track of species in trouble better than any I know. The Web site is easy to use. Just dial it up at

www.natureserve.org

and name your species. It offers good, detailed accounts of how a given species slipped into danger, where it continues to live, a history of efforts to help it, and what's being done for it now.

www.natureserve.org

and name your species. It offers good, detailed accounts of how a given species slipped into danger, where it continues to live, a history of efforts to help it, and what's being done for it now.

A fine book about animals that became extinct is Tim Flannery and Peter Schouten,

A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals

(New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001).

A Gap in Nature: Discovering the World's Extinct Animals

(New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001).

Betty the Crow's breakthrough was a media sensation. The story “Crow Makes Wire Hook to Get Food,” dated August 8, 2002, can be found on the National Geographic Web site. It even has, at this writing, moving pictures of Betty. The address is

www.Nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/08/0808_020808_crow.html

. For a magazine article, read “Shaping of Hooks in New Caledonian Crows,” in

Science,

vol. 297, no. 5583, p. 981.

www.Nationalgeographic.com/news/2002/08/0808_020808_crow.html

. For a magazine article, read “Shaping of Hooks in New Caledonian Crows,” in

Science,

vol. 297, no. 5583, p. 981.

If ever a book were like an ecosystem, this is it. I depended on the help of an interconnected web of scientists, conservationists, librarians, editors, guides, curators, translators, readers, and ordinary folks who often lived through extraordinary events.

For helping me comb through a mountain of material at Cornell University, I thank Susan Szasz Palmer and Elaine Engst of the Rare and Manuscript Collections Division. Likewise, Greg Budney and Marie Eckert at Cornell's Laboratory of Ornithology, Library of Natural Sounds, gave me much help and advice, and David G. Allen generously shared insights about his father, Arthur A. Allen.

For help in Madison Parish, Louisiana, I thank the Nature Conservancy's Keith Ouchley and Ronnie Ulmerâwho gave up two days of his valuable time to guide me. Thanks also to Geneva Williams, Jerome Ford, Ava Kahn, and Tolbert Williams and the Madison Parish courthouse staff. Mary Tebo shared her valuable insights on the clearing of the southern forests. Tony Howe taught me about railroads.

For material and insights about German prisoners of war in Louisiana, I thank John Cherbini, Mary Sims, and Matthew Schott.

For sharing childhood memories of their lives in and around the Singer Tract, I thank Robert Fought, Gene and Lynelle Laird, and especially Billy Louis Fought, who helped me constantly and repeatedly.

I thank my Nature Conservancy colleagues Tony Grundhauser, Dean Harrison, John Humke, Becky Abel, Mike Andrews, and Will Stolzenberg, and especially Pat Patterson.

I visited Cuba to research this book. There I covered much ground, conducted many interviews, and made lifelong friends. I'm deeply grateful to Arturo Kirkconnell, Carlos Peña, Xiomara Gálvez Aguilera, Nils Navarro, Michael Sánchez, Ernesto Reyes, and Eduardo Fidalgo Franco. I thank Elizabeth Garc

a Guerra for helping me find the stamp of the Cuban Ivory-bill. I thank Dr. Lester Short for sharing memories of his visits to Cuba and insights about woodpeckers. I must also express my appreciation to Maine Congressman Tom Allen and his indomitable staffer Mark Oulette for helping me obtain a license to travel to Cuba. I thank Giraldo Alayón, Aimé Posada, and Mariela Machado González for friendship, insight, and inspiration.

a Guerra for helping me find the stamp of the Cuban Ivory-bill. I thank Dr. Lester Short for sharing memories of his visits to Cuba and insights about woodpeckers. I must also express my appreciation to Maine Congressman Tom Allen and his indomitable staffer Mark Oulette for helping me obtain a license to travel to Cuba. I thank Giraldo Alayón, Aimé Posada, and Mariela Machado González for friendship, insight, and inspiration.

a Guerra for helping me find the stamp of the Cuban Ivory-bill. I thank Dr. Lester Short for sharing memories of his visits to Cuba and insights about woodpeckers. I must also express my appreciation to Maine Congressman Tom Allen and his indomitable staffer Mark Oulette for helping me obtain a license to travel to Cuba. I thank Giraldo Alayón, Aimé Posada, and Mariela Machado González for friendship, insight, and inspiration.

a Guerra for helping me find the stamp of the Cuban Ivory-bill. I thank Dr. Lester Short for sharing memories of his visits to Cuba and insights about woodpeckers. I must also express my appreciation to Maine Congressman Tom Allen and his indomitable staffer Mark Oulette for helping me obtain a license to travel to Cuba. I thank Giraldo Alayón, Aimé Posada, and Mariela Machado González for friendship, insight, and inspiration.I thank Longfellow Books, the world's greatest independent bookstore, especially Chris Bowe and Kirsten Cappy, for constant encouragement and uncritical love. The same goes for the Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance. For library research help, I thank Paul D'Alessandro of the Portland, Maine, Public Library, and Cassandra Fitzherbert and her fine staff at the University of Southern Maine's Interlibrary Loan Department.

I'm very grateful to Gavin Bauer and Tessa Hartley, both middle school students, who read this manuscript from front to back and gave me precise, constructive criticism. Thanks to Shoshana Hoose for reading and commenting on early drafts.

I can't thank my

amigo y compañero

Charles Duncan enough for going with me to Cuba, for translating, for taking photos, for helping me in so many ways. Likewise I thank the original Bromista, Ben Gregg, whose friendship means the world to me.

amigo y compañero

Charles Duncan enough for going with me to Cuba, for translating, for taking photos, for helping me in so many ways. Likewise I thank the original Bromista, Ben Gregg, whose friendship means the world to me.

Many scientists, including Dr. Davis Finch and Dr. David Wilcove, helped me evaluate facts and ideas and led me to materials concerning everything from grubs to extinction. Dr. Larry Master, Chief Zoologist for NatureServe, read much of the scientific material critically and saved me from embarrassing errors. Dr. James Van Remsen, Curator of Birds at the LSU Museum of Natural Science, actually encouraged me to bombard him with a year's worth of questions. I thank him so much. Dr. Daniel Simberloff of the University of Tennessee's Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology read, admonished, encouraged, guided and mentored me through a great deal of this project, even when the Lady Vols experienced shaky times. I admire and thank him more than I can ever tell him. I thank Dr. Robert E. Jenkins for inspiring this book by expressing faith in me long ago and putting me to work in service of biodiversity. He is a genius and a kind man.

I am deeply indebted to my brilliant, caring editor Melanie Kroupa for taking on this project with me and guiding me through it. I could not have a better teammate. Thanks also to her assistant Sharon McBride, to the keen-eyed copy editors, Elaine Chubb and Susan Goldfarb, and to Barbara Grzeslo for her elegant design.

I could not have written this book without the support of my family. As it was written,

Hannah Hoose flew off to college and Ruby Hoose entered middle school. I thank them both so much for being such splendid daughters and wonderful people.

Hannah Hoose flew off to college and Ruby Hoose entered middle school. I thank them both so much for being such splendid daughters and wonderful people.

Above all, I thank Nancy Tanner. I had no idea what to expect when I contacted James Tanner's widow. Would she talk to me? What would she think about this project? She became a partner, corresponding with me through countless e-mails, letting me visit her, combing through files and sending photos, articles, and letters, coming up with ideas, nudging me away from wrong paths, even giving me advice on proper technique for the crawl stroke. Now I realize this book would not have been remotely possible without her. And I ended up with a fine friend into the bargain.

Finally, I thank

Campephilus principalis,

who lives, as Giraldo Alayón put it, between magic and science. I am lucky to have shared the earth for at least part of my life with such a magnificent creature as the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

Campephilus principalis,

who lives, as Giraldo Alayón put it, between magic and science. I am lucky to have shared the earth for at least part of my life with such a magnificent creature as the Ivory-billed Woodpecker.

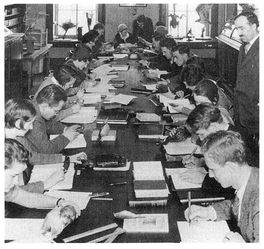

To learn about birds, ornithologists often find themselves in precarious situations. Here Jim Tanner tries to keep his balance as he inspects a Bald Eagle nest on Merritt Island, Florida, in 1935

Other books

Tennessee Takedown by Lena Diaz

Alamo Traces by Thomas Ricks Lindley

Unchained: A Biker Erotic Romance by Summers, A. L.

Pelquin's Comet by Ian Whates

The Highwayman's Footsteps by Nicola Morgan

The Cleaner (Born Bratva Book 4) by Suzanne Steele

The Understatement of the Year by Sarina Bowen

Just for Fun : The Story of an Accidental Revolutionary by Linus Benedict Torvalds

Center Stage (Bright Lights Billionaire #2) by Ali Parker

Giant George by Dave Nasser and Lynne Barrett-Lee