The Railway Detective Collection: The Railway Detective, the Excursion Train, the Railway Viaduct (The Railway Detective Series) (82 page)

Authors: Edward Marston

An hour later, he and Lady Hetherington were at either end of the long oak table in the dining room, eating their meal and engaging in desultory conversation. Sir Marcus was chastened by the turn of events. In being forced to kill Rogan, he felt that a chapter in his life had just been concluded. He had to accept that his plan to destroy the railway in France had failed. But at least he was safe. He could now resume his accepted routine, going through the social rounds in Essex with his wife and making regular trips to his club in London. Nobody would ever know that he had once been associated with a private detective named Luke Rogan.

When the servant entered the room, and apologised for the interruption, he shattered his master’s sense of security.

‘There’s an Inspector Colbeck to see you, Sir Marcus.’

‘Who?’ The old man almost choked.

‘Inspector Colbeck. He’s a detective from Scotland Yard and he has a Sergeant Leeming with him. They request a few moments of your time. What shall I tell them, Sir Marcus?’

‘Show them into the library,’ said the other, getting to his feet and dabbing at his mouth with a napkin. ‘Nothing to be alarmed about, my dear,’ he added to his wife. ‘It’s probably something to do with those poachers who’ve been bothering us. Do excuse me.’

The servant had already left. Before he followed him, Sir Marcus paused to kiss his wife gently on the cheek and squeeze her shoulder with absent-minded affection. Then he straightened his shoulders and went out. The detectives were waiting for him in the library, a long room that was lined with bookshelves on three walls, the other being covered with paintings of famous battles from the Napoleonic Wars. Many of the volumes there were devoted to military history.

Robert Colbeck introduced himself and his companion. He gave Sir Marcus no opportunity to remark on his facial injuries. His initial question was all the more unsettling for being delivered in a tone of studied politeness.

‘Are you acquainted with a man named Luke Rogan?’

‘No,’ replied Sir Marcus. ‘Never heard of him.’

‘You’ve never employed such an individual?’

‘Of course not.’

‘I notice a copy of

The Times

on the table over there,’ said Colbeck with a nod in that direction. ‘If you’ve read it, you’ll have encountered Rogan’s name there and know why we’ve taken such an interest in him. I’ve a particular reason for wanting to apprehend him, Sir Marcus. Earlier today, he did his best to kill me.’

‘Did you instruct him to do that, Sir Marcus?’ asked

Leeming.

‘Don’t be so preposterous, man!’ shouted the other.

‘It’s a logical assumption.’

‘It’s a brazen insult, Sergeant.’

‘Not if it’s true.’

‘Sergeant Leeming speaks with authority,’ said Colbeck, taking over again. ‘He called at your house in Pimlico this afternoon. According to the servant he met, Luke Rogan visited the house yesterday and spent some time in your company. I think that you are a liar, Sir Marcus.’ He gave an inquiring smile. ‘Do you regard that as an insult as well?’

The old man would not yield an inch. ‘You have no right to browbeat me in my own home,’ he said. ‘I must ask you to leave.’

‘And we must respectfully decline that invitation. We’ve spent far too long on this investigation to pay any heed to your bluster. The facts are these,’ Colbeck went on, brusquely. ‘You attended a lecture given by Gaston Chabal, who was working as an engineer on the railway between Mantes and Caen. Because that railway would one day connect Paris with a port that also houses an arsenal, you spied a danger of invasion. To avert that danger, you tried to bring the railway to a halt. That being the case, Chabal’s murder took on symbolic significance.’ His smile was much colder this time. ‘Do I need to go on, Sir Marcus?’

‘We are well aware of your military record,’ said Leeming. ‘You fought against the French for years. You can only ever see them as an enemy, can’t you?’

‘They

are

an enemy!’ roared Sir Marcus.

‘We’re at peace with them now.’

‘That’s only an illusion, Sergeant. I knew the rogues when

they held sway over a great part of Europe and plotted to add us to their empire. Thanks to us, Napoleon was stopped. It would be criminal to allow another Napoleon to succeed in his place.’

‘That’s why you had Chabal killed, isn’t it?’ said Colbeck. ‘He had the misfortune to be a Frenchman.’

Sir Marcus was scathing. ‘He embodied all the qualities of the breed,’ he said, letting his revulsion show. ‘Chabal was clever, arrogant and irredeemably smug. I’ll tell you something about him that you didn’t know, Inspector.’

‘Oh, I doubt that.’

‘Not content with building a railway to facilitate the invasion of England, he showed the instincts of a French soldier. Do you know what they do after a victory?’ he demanded, arms flailing. ‘They rape and pillage. They defile the womenfolk and steal anything they can lay their hands on. That was what Chabal did. His first victim was an Englishwoman. He not only subjected her to his carnal passions, he had the effrontery to inveigle money from her husband for the project in France. Rape and pillage – no more, no less.’

‘Considerably less, I’d say,’ argued Colbeck. ‘I spoke to the lady in question and she told me a very different story. She became Gaston Chabal’s lover of her own free will. She mourned his death.’

‘I saved her from complete humiliation.’

‘I dispute that, Sir Marcus.’

‘I did, Inspector. I had him followed, you see,’ said the old man, reliving the sequence of events. ‘I had him followed on both sides of the Channel until I knew all about him. None of it was to his credit. When he tried to take advantage of the lady during her husband’s absence, I had him killed on the

way there.’

‘And thrown from the Sankey Viaduct.’

‘That was intentional. It was a reminder of our superiority – a French civil engineer hurled from a masterpiece of English design.’

‘Chabal was dead at the time,’ said Leeming, shrugging his shouders, ‘so it would have been meaningless to him.’

Sir Marcus scowled. ‘It was not meaningless to me.’

‘We need take this interview no further,’ decided Colbeck. ‘I have a warrant for your arrest, Sir Marcus. Before I enforce it, I must ask you if Luke Rogan is here.’ The old man seemed to float off into a reverie. His gaze shifted to the battles depicted on the wall. He was miles away. Colbeck prompted him. ‘I put a question to you.’

‘Come with me, Inspector. You, too, Sergeant Leeming.’

Walking with great dignity, Sir Marcus Hetherington led them upstairs and along the landing. He unlocked the door of his shrine and conducted them in. Colbeck was astonished to see the range of memorabilia on show. The sight of the skull transfixed Leeming. Sir Marcus turned to the portrait of him in uniform.

‘That was painted when I got back from Waterloo,’ he said, proudly. ‘I lost a lot of friends in that battle and I lost two young sons as well. That broke my heart and destroyed my wife. I’ll never forgive the French for what they stole from us that day. They were

animals

.’

‘It was a long time ago,’ said Colbeck.

‘Not when I come in here. It feels like yesterday then.’

‘I asked you about Luke Rogan.’

‘Then I’ll give you an answer,’ said the old man, opening a drawer in the cabinet and taking out the wooden case. He

lifted the lid and took out one of the pistols before offering it to Colbeck. ‘That’s the weapon I used to kill Mr Rogan,’ he explained. ‘You’ll find his body at the bottom of the well.’

Leeming was astounded. ‘You

shot

him?’

‘He’d outlived his usefulness, Sergeant.’

‘It’s beautiful,’ said Colbeck, admiring the pistol and noting its finer points. ‘It was made by a real craftsman, Sir Marcus.’

‘So was this one, Inspector Colbeck.’

Before they realised what he was going to do, he took out the second gun, put it into his mouth and pulled the trigger. In the confined space, the report was deafening. His head seemed to explode. Blood spattered all over the portrait of Sir Marcus Hetherington.

Madeleine Andrews was dismayed. It was two days since the murder investigation had been concluded and she had seen no sign of Robert Colbeck. The newspapers had lauded him with fulsome praise and she had cut out one article about him. Yet he did not appear in person. She wondered if she should call at his house and, if he were not there, leave a message with his servant. In the end, she decided against such a move. She continued to wait and to feel sorely neglected.

It was late afternoon when a cab finally drew up outside the house. She opened the door in time to watch Colbeck paying the driver. When he turned round, she was horrified to see the bruises that still marked his face. There had been no mention of his injuries in the newspaper. Madeleine was so troubled by his appearance that she took scant notice of the object he was carrying. After giving her a kiss, Colbeck followed her into the house.

‘Before you ask,’ he explained, ‘I had a fight with Luke Rogan. Give me a few more days and I’ll look more like the man you know. And before you scold me for not coming sooner,’ he went on, ‘you should know that I went to Liverpool on your behalf.’

‘Liverpool?’

‘The local constabulary helped us in the first stages of our enquiries. It was only fair to give them an account of what transpired thereafter. I can’t say that Inspector Heyford was overjoyed to see me. He still hasn’t recovered from the shock of accepting Constable Praine as his future son-in-law.’

Madeleine was bemused. ‘Who are these people?’

‘I’ll tell you later, Madeleine,’ he promised. ‘The person I really went to see was Ambrose Hooper.’

‘The artist?’

‘The very same.’ He tapped the painting that he was holding. ‘I bought this from him as a present for you.’

‘A present?’ She was thrilled. ‘How marvellous!’

‘Aren’t you going to see what it is?’ Madeleine took the painting from him and began to unwrap it. ‘Because I was engaged in solving the crime, Mr Hooper gave me first refusal.’

Pulling off the last of the thick brown paper, she revealed the stunning watercolour of the Sankey Viaduct. It made her blink in awe.

‘This is amazing, Robert,’ she said, relishing every detail. ‘It makes my version look like a childish scribble.’

‘But

that

was the one that really helped me,’ he said. ‘You drew what was in Sir Marcus Hetherington’s mind. Two countries joined together by a viaduct – victorious France and defeated England.’

‘Is this Gaston Chabal?’ she asked, studying the tiny figure.

‘Yes, Madeleine.’

‘He really does seem to be falling through the air.’

‘Mr Hooper has captured the scene perfectly.’

‘No wonder you were so grateful to him at the start.’

‘He was the perfect witness – in the right place at the right time to record the moment for posterity. That painting is proof of the fact.’

‘It’s a wonderful piece of work. Father will be so interested to see it. He’s driven trains over the viaduct.’

‘I didn’t buy it for your father, I bought it for you. It was by way of thanks for your assistance. Do you really like the painting?’

‘I love it,’ she said, putting it aside so that she could fling her arms around his neck. ‘Thank you, Robert. You’re so kind.’ She kissed him. ‘It’s the nicest thing you’ve ever given me.’

‘Is it?’ he asked with a mischievous twinkle in his eye. ‘Oh, I think I can do a lot better than that, Madeleine.’

‘A grand romp very much in the tradition of Holmes and Watson. Packed with characters Dickens would have been proud of. Wonderful, well written’

Time Out

‘The past is brought to life with brilliant colours, combined with a perfect whodunit. Who needs more?’

The Guardian

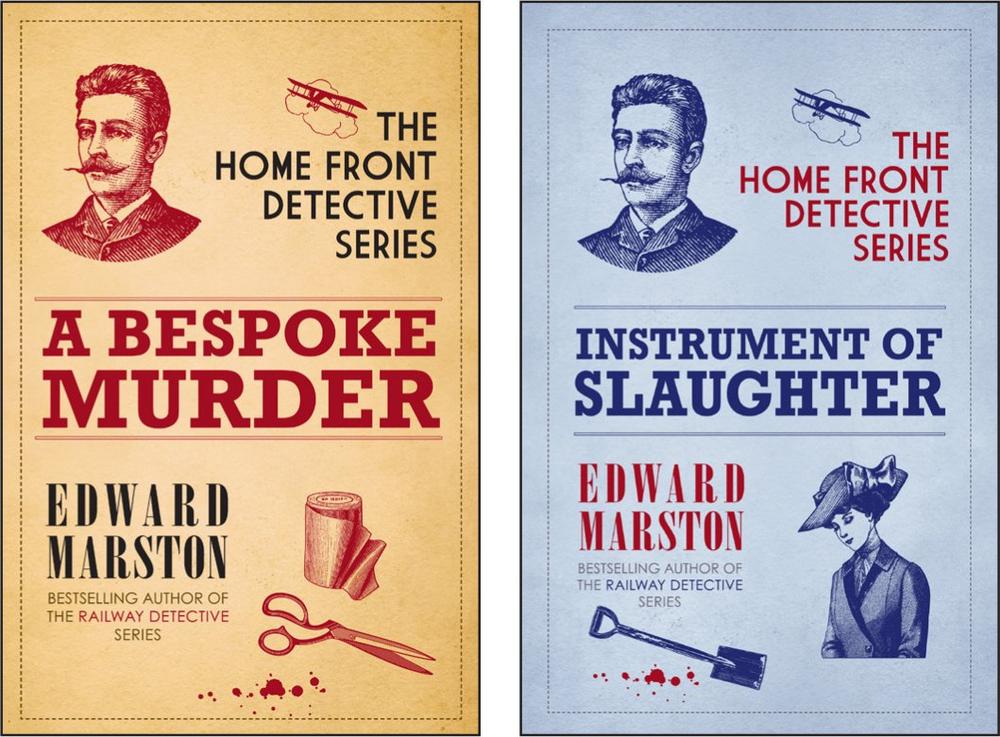

E

DWARD

M

ARSTON

was born and brought up in South Wales. A full-time writer for over forty years, he has worked in radio, film, television and the theatre and is a former chairman of the Crime Writers’ Association. Prolific and highly successful, he is equally at home writing children’s books or literary criticism, plays or biographies. He has now written ten books in the Railway Detective series featuring Inspector Robert Colbeck and Sergeant Victor Leeming.