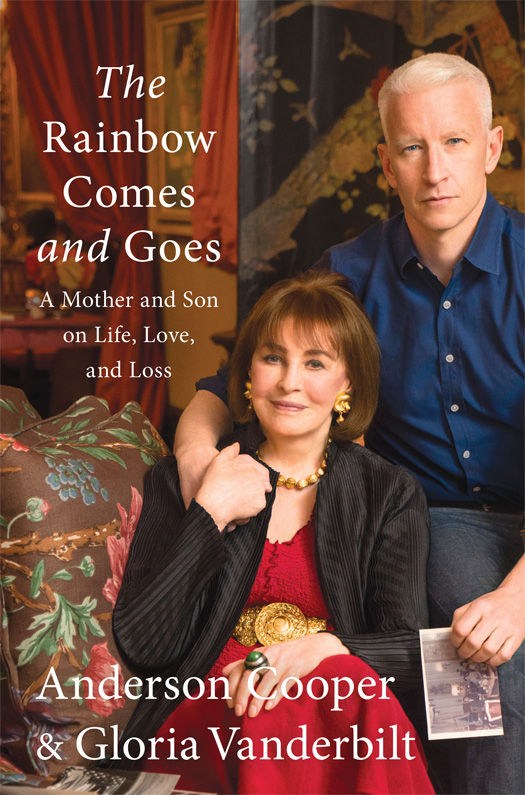

The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son On Life, Love, and Loss

Read The Rainbow Comes and Goes: A Mother and Son On Life, Love, and Loss Online

Authors: Anderson Cooper,Gloria Vanderbilt

Photo by George Hoyningen-Huene, courtesy of R. J. Horst/Staley Wise Gallery.

Contents

M

y mother comes from a vanished world, a place and a time that no longer exist. I have always thought of her as a visitor stranded here; an emissary from a distant star that burned out long ago.

Her name is Gloria Vanderbilt. When I was younger I used to try to hide that fact, not because I was ashamed of her—far from it—but because I wanted people to get to know me before they learned that I was her son.

Vanderbilt is a big name to carry, and I’ve always been glad I didn’t have to. I like being a Cooper. It’s less cumbersome, less likely to produce an awkward pause in the conversation when I’m introduced. Let’s face it, the name Vanderbilt has history, baggage. Even if you don’t know the details of my mom’s extraordinary story, her name comes with a whole set of expectations and assumptions about what she must be like. The reality of her life, however, is not what you’d imagine.

My mom has been famous for longer than just about anyone else alive today. Her birth made headlines, and for better or worse, she’s been in the public eye ever since. Her successes and failures have played out on a very brightly lit stage, and she has lived many different lives; she has been an actress, an artist, a designer, and a writer; she’s made fortunes, lost them, and made them back again. She has survived abuse, the loss of her parents, the death of a spouse, the suicide of a son, and countless other traumas and betrayals that might have defeated someone without her relentless determination.

Though she is a survivor, she has none of the toughness that word usually carries with it. She is the strongest person I know, but tough, she is not. She has never allowed herself to develop a protective layer of thick skin. She’s chosen to remain vulnerable, open to new experiences and possibilities, and because of that, she is the most youthful person I know.

My mom is now ninety-two, but she has never looked her age and she has rarely felt it, either. People often say about someone that age, “She’s as sharp as ever,” but my mom is actually

sharper

than ever. She sees her past in perspective.

The little things that once seemed important to her no longer are. She has clarity about her life that I am only beginning to have about mine.

At the beginning of 2015, several weeks before her ninety-first birthday, my mother developed a respiratory infection she couldn’t get rid of, and she became seriously ill for the first time in her life. She didn’t tell me how bad she felt, but as I was boarding a plane to cover a story overseas, I called her to let her know I was leaving, waiting until the last minute as usual because I never want her to worry. When she picked up the phone, immediately I knew something was wrong. Her breath was short, and she could barely speak.

I wish I could tell you I canceled my trip and rushed to her side, but I didn’t. I’m not sure if the idea she could be very ill even occurred to me; or perhaps it did, acting on it would have been just too inconvenient and I didn’t want to think about it. I was heading off on an assignment, and my team was already in the air. It was too late to back out.

Shortly after I left, she was rushed to the hospital, though I didn’t find this out until I had returned, and by then she was already back home.

For months afterward she was plagued with asthma and a continued respiratory infection. At times she was unsteady on her feet. The loss of agility was difficult for her, and there were many days when she didn’t get out of bed. Several of her

close friends had recently died, and she was feeling her age for the first time.

“I’d like to have several more years left,” she told me. “There are still things I’d like to create, and I’m very curious to see how it all turns out. What’s going to happen next?”

As her ninety-first birthday neared, I began to think about our relationship: the way it was when I was a child and how it was now. I started to wonder if we were as close as we could be.

The deaths of my father and brother had left us alone with each other, and we navigated the losses as best we could, each in our own way. My father died in 1978, when I was ten; and my brother, Carter, killed himself in 1988, when I was twenty-one, so my mom is the last person left from my immediate family, the last person alive who was close to me when I was a child.

We have never had what would be described as a conventional relationship. My mom wasn’t the kind of parent you would go to for practical advice about school or work. What she does know about are hard-earned truths, the kind of things you discover only by living an epic life filled with love and loss, tragedies and triumphs, big dreams and deep heartaches.

When I was growing up, though, my mom rarely talked about her life. Her past was always something of a mystery. Her parents and grandparents died before I was

born, and I knew little about the tumultuous events of her childhood, or of the years before she met my father, the events that shaped the person she had become. Even as an adult, I found there was still much I didn’t know about her—experiences she’d had, lessons she’d learned that she hadn’t passed on. In many cases, it was because I hadn’t asked. There was also much she didn’t know about me. When we’re young we all waste so much time being reserved or embarrassed with our parents, resenting them or wishing they and we were entirely different people.

This changes when we become adults, but we don’t often explore new ways of talking and conversing, and we put off discussing complex issues or raising difficult questions. We think we’ll do it one day, in the future, but life gets in the way, and then it’s too late.

I didn’t want there to be anything left unsaid between my mother and me, so on her ninety-first birthday I decided to start a new kind of conversation with her, a conversation about her life. Not the mundane details, but the things that really matter, her experiences that I didn’t know about or fully understand.

We started the conversation through e-mail and continued it for most of the following year. My mom had only started to use e-mail recently. At first her notes were one or

two lines long, but as she became more comfortable typing, she began sending me very detailed ones. As you will see in the pages ahead, her memories are remarkably intimate and deeply personal, revealing things to me she never said face-to-face.

The first e-mail she sent me was on the morning of her birthday.

91 years ago on this day, I was born.

I recall a note from my Aunt Gertrude, received on a birthday long ago.

“Just think, today you are 17 whole years old!” she wrote.

Well, today—I am 91 whole years old—a hell of a lot wiser, but somewhere still 17.

What is the answer?

What is the secret?

Is there one?

That e-mail and its three questions started the conversation that ended up changing our relationship, bringing us closer than either of us had ever thought possible.

It’s the kind of conversation I think many parents and their grown children would like to have, and it has made this past year the most valuable of my life. By breaking down the walls of silence that existed between us, I have

come to understand my mom and myself in ways I never imagined.

I know now that it’s never too late to change the relationship you have with someone important in your life: a parent, a child, a lover, a friend. All it takes is a willingness to be honest and to shed your old skin, to let go of the long-standing assumptions and slights you still cling to.

I hope what follows will encourage you to think about your own relationships and perhaps help you start a new kind of conversation with someone you love.

After all, if not now, when?