The Rape of Europa (18 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

Paul Rosenberg

Georges Wildenstein put 329 objects into the Banque de France in Paris

and had some 82 taken in by the Louvre, but plenty were left in his showrooms at 57, rue la Boétie, and in his house outside Paris when he and his family fled to Aix-en-Provence. The Rothschild items sheltered by the Louvre represented only a fraction of the family’s enormous holdings, which remained scattered all over France. Miriam de Rothschild, known for her vagueness, lost forever much of her collection which she buried in an unmarked sand dune near Dieppe.

24

More cautious, the Bernheim-Jeune family sent 28 paintings, 7 of them by Cézanne, to friends at the Château de Rastignac in the Dordogne, to be carefully hidden in trunks, closets, and cabinets. Other pictures went with the family to Nice, but the apartment in Paris remained full of sculpture, drawings, and paintings of great quality.

25

And the jeweler Henri Vever put his Rembrandt etchings in his Paris bank, but took his beloved and incomparable collection of Islamic miniatures and books with him to his château in Normandy.

Georges Wildenstein, London, 1938 (Photo by Cecil Beaton)

If the quantities involved in all these arrangements seem impressive, they pale by comparison to the shipment successfully moved through France and Spain to Lisbon during May and June by the dealer Martin Fabiani. After the death of the legendary Ambroise Vollard in July 1939, his brother Lucien had sold much of his share of the collection to Fabiani, who had worked with Vollard for years. The pictures, which had been delivered only weeks before the invasion,

26

were a staggering group: 429 paintings, drawings, and watercolors by Renoir; 68 Cézannes, 57 Rouaults, 13 Gauguins, and so forth, to a grand total of 635. British export papers having been granted, they left Lisbon on September 25, 1940, on the SS

Excalibur

, the same ship which had just transported the Duke and Duchess of Windsor to semi-exile in Bermuda.

Fabiani believed that works of this nature would be considerably more salable in the United States or perhaps Britain than to the new rulers of

France; to this end he had entered into a profit-sharing agreement with Etienne Bignou, New York, and Reid and Lefèvre, London.

27

But alas, by the time the

Excalibur

neared Bermuda, continental France was regarded by the British not as an ally, but as an enemy economy whose foreign exchange could be used to sustain Nazi aggression, now aimed squarely at England. All British consuls, working with the Ministry of Economic Warfare, had been alerted to the export of “enemy” assets, and all shipments were carefully checked when they arrived at British-controlled ports. In Bermuda, “on account of their enemy origin, and of doubts about the sympathies of Fabiani,” the pictures were removed, placed in prise, and later stored in Canada in the charge of the Registrar of the Exchequer Court. There they would remain until the end of the war.

28

Even those most versed in the little subterfuges of international trade would find that their careful plans were not only of no avail but had suddenly become quite illegal. A few weeks after the Fabiani affair, David David-Weill, head of the famed Lazard Frères international bank, sent twenty-six cases of paintings and antiquities off to Lisbon, where they too eventually embarked on the busy SS

Excalibur.

Their destination was New York, where they were to be sold by the Wildenstein branch incorporated there. There was nothing new about this arrangement. In 1931 M. David-Weill had transferred part of his collection to a British holding company called Anglo-Continental Art, Inc., which in turn was owned by a Canadian corporation also entirely owned by David-Weill. Parts of the collection had also been consigned to Wildenstein, London, for sale. Wildenstein, searching for a wider market, sent six shipments of these works to its New York branch in 1937 and 1938. There were some 291 items, valued at more than $2 million. The works on the

Excalibur

would join those in New York as property of Anglo-Continental.

But the cases, once in Lisbon, were at first refused an export certification by the British. Cables flew back and forth between Lazard branches in London and New York, referring to David-Weill only as “our common friend” in case of German intercepts, and imploring London to “use their best efforts to clear the shipment.” The London office revealed that the British had heard that the works were to be exhibited and sold in New York in order to raise funds for the French “Secours National,” which had suddenly become an enemy organization. This was denied, and appeals were made to the British embassy in Washington, which helpfully pointed out that the principal motivation was to keep the collection from the Germans. The shipment was finally allowed to leave Lisbon in October 1941, and arrived safely in New York, where it was supposed to be held in a blocked account.

The reluctance of the British to allow the David-Weill collection to be

sold had resulted from the fact that all the proceeds of sales of the objects previously sent to New York from London had not been sent back to foreign-currency-starved Britain, nominal base of Anglo-Continental Art. The Bank of England, in its efforts to keep dollars flowing to England, now threatened to force immediate liquidation of the entire collection at one time, which would have the effect of lowering prices. This was made clear to Wildenstein in several anxious letters from Anglo-Continental in London imploring them to remit the disputed amounts immediately. Things were made worse by the entry of the Canadians on the scene, who also claimed the credits.

All these machinations inevitably came to the notice of United States Treasury authorities monitoring the flow of foreign funds into and out of the country. Under American law, all remittances to nations under German control had to be reported and licensed, and the David-Weill shipment had unquestionably originated in France. T-men soon descended on the elegant premises of Wildenstein, New York, where the partners were found to have violated these American regulations by having sent off the very proceeds for which London clamored.

Matters were not improved by Wildenstein’s transparently false claim that they were not sure who exactly owned the collection, admitting only that “there is a possibility of a French interest being involved.” The T-men thought it was all an “attempt to confuse the English, Canadian, and United States authorities as to the true ownership of the collection, and in the meantime enjoy absolute freedom in the manner in which the collection was to be managed.” The entire assets of Anglo-Continental were immediately frozen by the American authorities, proper licenses were obtained by Wildenstein, and proceeds from all further sales ordered to be held in a blocked account in a New York bank. This was fine with Anglo-Continental’s lawyer, who all along had wanted to keep everything in the safety of the USA. For many in the art trade, who preferred to operate just as the T-men described, this unwanted scrutiny was, particularly in the circumstances, a serious blow.

29

The fall of France caused upheavals beyond that country’s borders. The British collections which had been evacuated to Wales, as far as one could get from aircraft coming from Germany proper, now lay directly in the path of German raiders flying from their new bases in France to attack the industrial cities of the Midlands. Although Bangor and its surroundings were not targets, even the remote possibility that a random bomb might wipe out the National Gallery’s holdings was worrisome. At first it was decided to distribute the works over a larger area. Some two hundred pictures

of “supreme importance” were divided among a house in Bontnewydd, Lord Lisburne’s estate near Aberystwyth, and Caernarvon Castle. In the first two the landlords were treated to unheard-of electric heating, far better than the ancient hot-water system at Caernarvon, where the humidity was controlled by dipping old blankets and felt in a nearby stream and hanging them among the paintings. Such logistical problems made these arrangements far from ideal, and in July, as the fear of a German invasion mounted and the air war intensified, the Gallery trustees decided to look for underground accommodations. Technical experts Martin Davies and Ian Rawlins set off across the wild landscapes of Wales, exploring “quarries, deep defiles capable of being roofed with reinforced concrete, railway tunnels, disused caves and so forth.” It was not, at first, an encouraging tour. Most of the sites were immediately rejected. “Access to … quarries we had seen, although perfect for the transport of slates … filled Mr. Rawlins and myself with despair when we thought of the National Gallery pictures,” wrote Davies. But in mid-September they finally discovered Manod Quarry, near Festinogg, which did have a rough road of sorts—four miles long with a gradient of 1 in 6—and a cooperative owner, who agreed not only to give them the space they needed but to double

the size of the entrance, which would allow the cases of pictures to be unloaded inside.

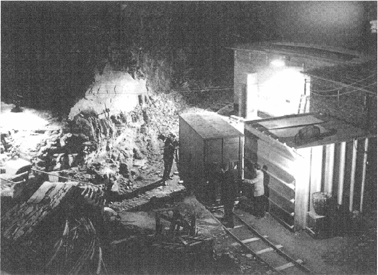

London’s National Gallery pictures go underground in the wilds of Wales.

Fixing up the interior was no small job. Five thousand tons of slate rock had to be blasted from the floors in order to level them, and six whole buildings in which humidity and light could be controlled had to be constructed over an area of half a square mile inside the cavern. The first pictures could not be moved in until August 1941. What had been so carefully spread out now had to be brought together. Six or seven hundred pictures a week crawled up to the quarry in howling winds on a road so narrow that two trucks could not pass. Once there, cases weighing thousands of pounds had to be inched down, without cranes, onto little motorized trolleys which moved them into the buildings. Inside, there was enough wall space to hang most of the collection, “not in a pleasing way, but well enough to inspect how they behaved underground”—which, due to the excellent temperature control and absence of the public, “who are enough to disturb the most careful air conditioning,” was better than at home.

30

Other refuges were prepared in the West Country for the British Museum and the Victoria and Albert. And the bombs did come. The National Gallery was hit nine times. An oil bomb went straight through the dome of the main reading room of the British Museum; others destroyed the roof of the new Parthenon Gallery recently given by Lord Duveen. The Tate, whose collections had also been regrouped from their original refuges to Sudley Castle in Gloucestershire, was hit over and over again, until all of its galleries were unusable. Director Rothenstein, looking down from what was left of the roof, saw

Other books

Fall of Knight by Peter David

The Borgia Ring by Michael White

The Realms of Ethair by Cecilia Beatriz

A World Apart (The Hands of Time: Book 3) by Irina Shapiro

Acquired Motives (Dr. Sylvia Strange Book 2) by Sarah Lovett

Bedlam by Morton, B.A.

Brief Loves That Live Forever by Andreï Makine

The Wolf's Mate Book 5: Bo & Reika by Butler, R.E.

0449474001339292671 4 fighting faer by Unknown