The Rape of Europa (27 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

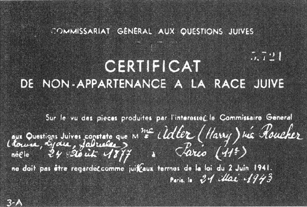

Later, all storage and moving companies, including American Express, were required to send in lists of customers, as their Dutch colleagues had already been forced to do. Victims who protested could, by proving they were Aryan and obtaining a

“Certificat de non-appartenance à la race juive,”

often reclaim their belongings. The files of the endless and desperate correspondence involved in these efforts survives. A certain Mme Seligman, the Aryan widow of a Jew, was exempted, but only after she had proved that her husband had been taken hostage and shot by the Gestapo.

54

Another man had to produce the birth data of his great-grandparents before the ERR gave up. The lists of what was taken survive too, infinitely more touching than lists of Rembrandts in their revelation of just how the smallest lives were affected: “5 ladies’ nightgowns, 2 children’s coats, 1 platter, 2 liqueur glasses, 1 man’s coat….”

By August 8, 1944, when they really had to stop, the Allies being by then just outside Le Mans, the ERR had raided 71,619 dwellings, and shipped off more than 1,079,373 cubic meters of goods in 29,436 railroad cars. By this time victims of bombings in Germany proper—of which a suspiciously high percentage were classified as “Police, SS Division, and private orders”—had also been made eligible to share the take. Some of

the thinking on the use of confiscated items was quite creative: special crates containing everything that was necessary for a “full kitchen for four bombing victims” were put together, including the sink. Alas, the final M-Aktion report complains, despite the sharpest controls, much of their hard work was sabotaged by French, Belgian, and Dutch railroad workers. Still, overall the project was, for the Nazis, a huge success.

55

Certificate of Aryanism

Parallel to this low-level looting was the more industrial attack on the statues and church bells of France and the Low Countries which were to be melted down for the factories of the Reich. In France the removal order was issued by Pétain. The process was billed in one magazine as a solution to the “constant problem of statuomania … more than ninety-two statues chosen from the most ugly and ridiculous have been taken down.” The writer suggests that they should be replaced by statues from the Louvre, “which after all were conceived for the open.”

56

Needless to say, the choice of which statues were to be sacrificed, which was left to the French at first, was hotly discussed in hopes of delaying the fatal moment. In the end, in addition to the more obvious politicians and generals, Voltaire and even La Fontaine were dragged off along with crocodiles, centaurs, Tritons, and Victor Hugo, whose empty pedestal was declared by one wit to look better than the statue had. Only a few, among them Joan of Arc and Louis XIV, were spared.

57

Although they had never seen the Kümmel Report, the French museum authorities had few illusions that their occupiers would limit themselves to

the Jewish collections. Their first instinct was to consolidate as much as they could under the wing of the Musées Nationaux. The Provincial Museums were, therefore, brought under their administration in April 1941. As little as possible was revealed, even within the Beaux-Arts offices, about the exact locations of things, in hopes that the enemy would simply overlook certain items. There were plenty of indications, however, that the Germans would eventually do as they pleased. First to go were some 2,000 objects, including 150 large cannon, granted of “German” origin, from the Military Museum at the Invalides, which were called war booty. More went from the Air Museum to the Luftwaffe. The libraries and many of the collections of Alsace-Lorraine, now a German Gau, had been removed from their storage places in the interior and taken back for the edification of the conquerors. Only the treasures and stained glass of the Cathedral of Strasbourg remained in the Dordogne, and these would finally be taken by force from the exiled Bishop in 1944.

The French also feared that the Italians might now reclaim works taken in the Napoleonic Wars, such as Veronese’s

Wedding at Cana.

This was considered enough of a possibility that the Louvre archivist, Lucie Mazauric, had been sent back to Chambord only days after the fall of France to retrieve the documents proving the French right of ownership that had been granted by various treaties signed during the Revolution and the Empire and by the exchange of certain works with Italy and Austria in 1815. For Mlle Mazauric it was a frightening and humiliating journey through the new German checkpoints. Once at Chambord, she did not dare put the bulky documents in her car, and instead spent forty-eight sleepless hours copying the information, after which she scattered the originals among less interesting files. This labor of love was never put to the test.

58

Soon after the fall of France, Jaujard had persuaded the sympathetic Metternich to allow the works evacuated to Loc-Dieu to be placed in other repositories with better conditions. Above all they needed space. At Loc-Dieu the hastily delivered cases were so crowded that they could not be opened, and every attempt at an inventory had resulted in a different total. In good weather the guardians resorted to spreading the pictures out on the lawns of the abbey, giving a never-before-seen vision of their Lorrains and Poussins. By September 1940 it was decided to move the three thousand paintings to the Ingres Museum at Montauban, a good location, dry and roomy. But having their masterpieces together in one place where fire could destroy them all was nerve-wracking. Intermittent crises such as leaks and a threatened roof cave-in kept everyone alert, as did a visit by Metternich. Pétain came too, and made museum history by exclaiming, when shown Murillo’s

Assumption of the Virgin

, in which the Blessed

Mother is surrounded by a host of little angels, “What a lot of children for a Virgin!”

59

Looking at the art was not, however, his real reason for being there. Pétain had decided in December 1940 to reward his neighbor General Franco for his continued neutrality by giving him some of the Spanish masterpieces in the French collections. One of these was the Murillo; also on the list were the ancient statue called the

Dama de Elche

and several Visigothic crowns found near Toledo by a French archaeologist who had sold them to the Cluny Museum.

The administrators of the Musées were helpless to prevent this entirely, but cleverly devised a strategy which would set an important precedent for the future: they would persuade Spain to accept the works in exchange for items of similar value from the Spanish collections. Jacques Jaujard, René Huyghe, and several others set off to negotiate with Madrid. To his credit, Franco immediately agreed to this proposal by the men who had, after all, helped save the entire Prado collection only a few years before. After months of agonizing, the Spanish museums sent a Greco portrait of Covarrubias, a Velázquez, and a number of drawings to France. Pétain was not entirely happy that his “gift” had become a trade. A Greco

Adoration

, which the Spanish were about to throw in, was removed from the list by a peremptory telegram from Vichy.

60

The resolution of this deal came just in time to counter an attempt by von Ribbentrop to appropriate Boucher’s

Diana Bathing

, one of the Louvre’s greatest masterpieces. The Foreign Minister had hinted at his desire to possess the picture in the fall of 1940, and left negotiations in the hands of Ambassador Abetz, who by now had been pushed out of the confiscation business by the ERR. But Abetz had enough influence at Vichy to order the picture brought to Paris from Montauban. From there it was whisked off to Berlin. In exchange, Abetz offered the French an Impressionist painting from the confiscated stores he had held back from the ERR. This was not considered an adequate trade. To be fair, the Louvre argued, a picture of the same period and quality, such as Watteau’s incomparable

Gersaint’s Shopsign

from the Charlottenburg Palace in Berlin, should replace the Boucher.

The idea was immediately rejected by the German museum administration, who were not inclined to diminish their collections for von Ribbentrop’s pleasure. The Foreign Minister felt constrained to return the picture, but wrote huffily to Abetz that the German museums might consider the exchange on their own “so that this example of eighteenth-century French painting would not be lost to Germany.” Abetz was instructed to keep track of the whereabouts of the Boucher at all times. He reassured his nervous

boss that a simple phone call would suffice if he really wanted the picture, after which they could decide if “they should give the French anything in exchange.”

61

Hitler had fewer qualms about this sort of thing than von Ribbentrop. In June 1942 his power was at its apogee. German forces were winning in North Africa, had reached the Black Sea, and were approaching Stalingrad, the important industrial city on the Volga. He envisioned nothing less than a meeting of his armies in the Middle East, and total control of the Eastern Mediterranean. Mussolini was so excited that he flew to Tripoli to get ready for the victory parade in Cairo.

It was in this mood that the Führer decided to erase the last vestiges of the Versailles Treaty and begin the recovery of the treasures stolen from the German nation. At the top of the list were the Ghent altarpiece by Jan van Eyck and the Dirk Bouts

Last Supper

from Louvain, elements of both of which had been claimed by Belgium from Germany in 1918. The retrievals were entrusted to Hitler’s early adviser, Dr. Ernst Buchner, head of the Bavarian Museums, and not to any of the established Nazi art-gathering agencies. The whole enterprise was undertaken in strictest secrecy. Correspondence implies that the reason for the removals was protection from air raids, but constant mention of the Versailles Treaty in the letters betrays the truth. For the van Eyck sortie, Dr. Buchner put together his own team in Munich. One week before departure Buchner wrote to ask the Führer if he was to bring back only the panels which had previously belonged to Berlin, or the whole thing. The answer does not survive, but after Buchner had arrived home with the whole altarpiece he wrote excitedly to his colleague Dr. Zimmermann in Berlin to tell him the good news, adding that “on the express orders of the Führerkanzlei” the “panels which were not earlier the property of the Berlin museum” had been brought back too.

The little convoy of one truck and one car crossed into Vichy France just east of Bayonne on July 29. M. Molle, the French curator in charge of the repository at Pau, refused to hand over the altarpiece, having been told that three authorizations, from the Direction des Musées, the director of Beaux-Arts in Belgium, and the Kunstschutz, were necessary for its release. Buchner’s escort called Vichy and the German embassy, but it was surely Buchner’s own call to the Reichschancellery which had the most effect. A few hours later a telegram arrived from Vichy chief of government Pierre Laval himself ordering the transfer. The panels were carefully examined, packed, and loaded on the truck. Buchner gave Molle a receipt and left. The altarpiece was well on its way to storage at Neuschwanstein before any of the French museum authorities or the Kunstschutz could be alerted.

Conveniently enough, Count Metternich, who had so consistently recommended that nothing be removed “until the Peace Conference,” had been sent on permanent leave only a few weeks before.

A similar operation was carried out a month later in Louvain to retrieve the Bouts

Last Supper.

After the war Buchner claimed that he had been “surprised” by these missions and had never found out whose idea they were. Be that as it may, he did not recommend against them, and a memo from the Reichschancellery regarding the Louvain operation notes that “General Director Buchner, in a letter to Dr. Hansen of the Party Chancellery, suggested that the four panels of the Louvain altarpiece, which are in danger of bomb damage there, be, in the process of compensation for the injustices inflicted on Germany by the Versailles Treaty, taken to a safe place in Bavaria.”

62

Reaction to these thefts, if somewhat delayed by the secrecy surrounding the events, was dramatic. The Belgians protested strongly. Jaujard wrote to Beaux-Arts director Louis Hautecoeur that every rule and arrangement to which the Belgians and the Kunstschutz had agreed had been violated, which would give the French museums a bad name. In November a meeting of the Comité des Musées, made up of representatives of all the Musées Nationaux, was called to protest the action further. Despite the dangers of such a gathering, which clearly had political overtones, not a single curator stayed away. A petition was drawn up demanding the return of the altarpieces. The Belgians, somewhat rashly, declared they would send curators to Pau to retrieve other works stored there, implying that the French were not to be trusted, though they did have the grace to thank Jaujard and his staff for their courage.

Other books

Etched in Silver: An Otherworld Novella by Yasmine Galenorn

The Children by Howard Fast

Captivated by the Soldier (BWWM Interracial Romance) by Dez Burke

Kidnapping the Brazilian Tycoon by Carmen Falcone

The Secret Book Club by Ann M. Martin

Blade of Fortriu by Juliet Marillier

Second Chance Christmas (The Colorado Cades) by Michaels, Tanya

Champion by Jon Kiln

A Fighting Man by Sandrine Gasq-Dion

Melissa's Acceptance by Becca van