The Rape of Europa (63 page)

Read The Rape of Europa Online

Authors: Lynn H. Nicholas

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #Art, #General

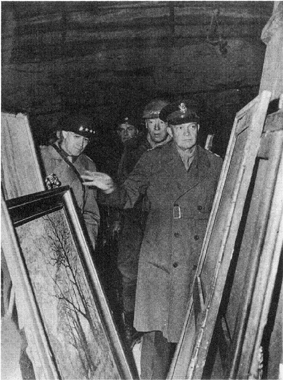

Generals Bradley, Patton, and Eisenhower examine paintings found alongside the tons of bullion hidden at Merkers.

Stout by now had found Dr. Rave, who told him of the forty-five Kaiser Friedrich Museum cases at Ransbach, which they could not inspect as the mine elevator was out of order. At Merkers itself, in addition to the crated items, there were approximately four hundred paintings from the Nationalgalerie without any protection at all. After calculating what materials he would need for normal packing, Stout noted that there was “no chance of getting them.” On Friday the thirteenth he returned to Ransbach and found that seven of the Kaiser Friedrich cases had been rifled and left in disorder: “Domenico Veneziano profile

Portrait of a Young Woman

lying out on box with about a dozen other works. Case #10 very important—Dürer, Holbein, Dom. Venez. and others.” But no paintings seemed to be missing. Stored along with the pictures were more than 1.5 million books and the costumes and properties of the Berlin State Theater and Opera. These too

had been ransacked, according to mine guardians, by Russian and Polish forced laborers. Rave thought that the Russian DPs, who, he noticed, always crossed themselves when they saw pictures of the Madonna, had not dared touch the mostly religious works in the Kaiser Friedrich cases, and had limited themselves to taking the more useful costumes.

On the same Friday afternoon Stout was informed by Bernstein that the art convoy would leave on Monday morning, “a rash procedure, and ascribed to military necessity,” i.e., the huge Russian offensive which the visiting generals expected at any moment. Nearly a million Soviet soldiers were preparing to take Berlin and meet the strung-out British and American armies just about where the mines full of treasure lay. Behind the American front the conquered part of Germany, its armies still fighting, was in chaos, with no government, peopled by wandering millions of DPs, surrendering soldiers, and hungry citizens. Bernstein therefore felt the need to get the treasure to a secure place immediately.

The gold operation was well under way by the next day. There were no transportation problems now. Jeeps with trailers had been lowered into the mine to bring the ingots to the elevators. Each load was carefully escorted and listed as it went into thirty-two ten-ton trucks sent from Frankfurt. The crews worked throughout the night. At midnight on Saturday the fourteenth Bernstein told the Monuments officers to prepare three truckloads of art which were to be mixed in with the gold to make the loads lighter. Stout, between 2:00 and 4:30 a.m., got the proper quantity of cased objects to the mine shaft, complete with inventory lists. The gold convoy departed at 8:45 Sunday morning, escorted by two machine-gun platoons, ten mobile antiaircraft units, continual air cover, and a large number of infantrymen.

After the departure of the gold a crew of twenty-five exhausted soldiers began the delicate task of moving the four hundred unpacked pictures up from the mine chambers. To prevent the formation of salt crystals. Rave carefully washed each one as it came into the open air. At noon fifty men were added to the complement, but Stout noted that there were now “difficulties keeping men on job and with streams of salt water in main shaft.” Once the pictures were in the upper mine building, they had to be wrapped in something for their journey. In his inspections of neighboring mines Stout had come across more than a thousand long sheepskin coats which had never made it to the freezing Wehrmacht troops on the Eastern Front. They would do their duty in this move and many subsequent ones. On Monday, with the help of a crew of prisoners of war, the trucks were loaded, a task that took more than twelve hours. The art convoy left Merkers on April 17, 1945, again with a spectacular escort.

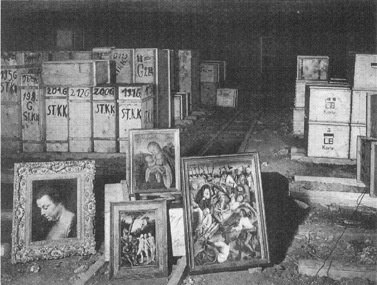

Looted pictures discovered intact in the Heilbronn mine (Photo by Helga Glassner)

The unloading, performed “by 105 prisoners of war in poor health” at the Reichsbank in Frankfurt, Stout described laconically as “complicated.” The facilities there were not good. Three hundred ninety-three uncrated paintings, 2,091 print boxes, 1,214 crates, and 140 bundles of textiles were jammed into nine dampish rooms. For the moment responsibility for the cream of the Kaiser Friedrich, Queen Nefertiti, and much more was in the hands of the Financial Section of SHAEF. This made some of the brass nervous, and Stout was ordered to return as soon as possible to make a complete inventory. The anxiety was justified. On every subsequent visit Stout, who was trying to keep the objects from each museum together, found that the cases and paintings had been carelessly moved about. Eventually he managed to get everything up to the ground floor, but upon reinspection found them “stored in promiscuous fashion.” And day by day the Reichsbank, the only official military depository, became more crowded as Colonel Bernstein’s teams continued to scour bank vaults and hiding places for gold and currency which they brought in by the ton.

10

These deliveries would soon stop, but the flow of works of art had just begun.

Thanks to the continuing efforts of LaFarge and his staff at SHAEF headquarters, still inconveniently located in France, the weary Stout was at least getting a little more help. Rorimer had arrived from Paris, as had Lamont Moore, a former National Gallery employee, who on April 4 reported “important repositories in combat lines near Magdeburg.” This was the Schönebeck-Grasleben complex, which, with gold on his mind, the local commander had immediately put under the same heavy guard as Merkers. The gold was not what he expected: Moore and Keck found, not bullion, but thousands of Polish church treasures. Farther west Rorimer, now with Seventh Army, had reported the discovery of a cache in the twin Kochendorf mines at Heilbronn just north of Stuttgart, while almost simultaneous pleas for help had come from Hancock, from a place called Bernterode in Thuringia.

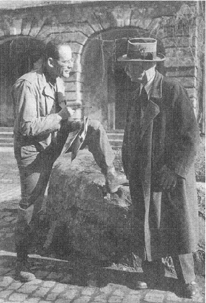

Lincoln Kirstein questions a custodian at Hungen.

Heilbronn, the storage place for the museums and libraries of Alsace and Heidelberg, was flooded, its body-strewn buildings smoldering with sporadic flare-ups of flame, and jammed with Polish and Russian DPs and terrified civilians. For lack of engineering or any other support, Rorimer was forced, for the time being, to leave the mine to military guards and German mine personnel, whose political leanings were as yet unclear.

11

Posey and Kirstein had meanwhile discovered eight large buildings full of Jewish books, anti-Semitic clippings, and religious objects from all over Europe, in the town of Hungen, where they had been stockpiled for the future use of Rosenberg’s racial studies institute, which was to have been built at Chiemsee in Bavaria.

12

Flying from one headquarters to another, with intermittent visits to

SHAEF, Stout begged for what he needed: at least 250 men to guard the repositories already discovered, access to trucks, and, above all, someplace to take the incredible quantities of art they had found, which they now knew would be hugely increased once the ERR and Linz stores were captured. These recommendations went out in reports and requests which Stout wrote night after night after his grueling day’s work was done. He did not get to Bernterode until May 1.

This mine was the last place in the world one might expect to find works of art, for it was a huge munitions dump filled by the German High Command with four hundred thousand tons of ammunition and many more tons of military supplies. In its twenty-three kilometers of corridors and chambers more than seven hundred French, Italian, and Russian slave laborers had been employed. But in mid-March all the civilians had been sent away and, it was reported by the DPs, German military units had brought numerous transports to the mine, which had been completely sealed on April 2. An American ordinance unit with bomb disposal experts had discovered it on April 27. Five hundred meters down the main corridor they had noticed a freshly built brick wall. Breaking through proved quite difficult: the brick was five feet thick, and behind it was a locked door.

Never in their wildest dreams could the Americans have envisioned what they now saw: in the partitioned room were four enormous caskets, one decorated with a wreath and ribbons bearing Nazi symbols and the name Adolf Hitler in large letters. Hung over the caskets and carefully placed about the chamber were numbers of German regimental banners. Boxes, paintings, and tapestries were stacked in one area. Wary of booby traps, the frightened men, sure they had found the Führer’s tomb, posted a guard and called their superiors at First Army. Further inspection revealed “a richly jeweled sceptre and orb, two crowns, and two swords with finely wrought gold and silver scabbards.” To Hancock, who arrived the next day, the theatrical arrangement clearly seemed to be a shrine, suggesting “the setting for a pagan ritual.” And indeed the coffins, hastily marked with handwritten cards taped to the tops, contained the remains, not of Hitler, but of three of Germany’s most revered rulers: Field Marshal von Hindenburg, Frederick the Great, and Frederick William I, a fact confirmed by the bomb experts, who, taking no chances, had checked inside and seen the shrivelled but well-embalmed remains of the once plump “Soldier-King.” The fourth coffin belonged to von Hindenburg’s wife. Next to them was a little metal box containing twenty-four photographs of contemporary Field Marshals, topped by one of Hitler. Above were 225 banners dating from the earliest Prussian wars to World War I. In three boxes were the Prussian crown regalia, which in addition to the things already

listed included a magnificent plumed

Totenhelm.

A little note assured any finder that there were no jewels in the crowns as these had been removed “for honorable sale.”

In the excitement Hancock had not at first paid much attention to the pictures. There were 271 in all, strangely at odds with the military splendor about them. Among the first he examined were, to his amazement, Watteau’s magnificent

Embarkation for Cythera

from the Charlottenburg Palace, Boucher’s

Venus and Adonis

, Chardin’s

La Cuisinière

, and several Lancrets. More in keeping with the ambience was a series of Cranachs. A large number were court portraits from the Palace of Sans Souci at Potsdam. Close examination of the whole room, to which there was only one entrance which had been locked from the inside, produced a final mystery: how had those who had brought all this in come out?

Removing the huge coffins would not be easy. To help out, First Army sent Lieutenant Steve Kovalyak, whose ability to circumvent Army regulations and obtain equipment became so invaluable to the MFAA men that they enlisted him permanently in their number. Packing started on May 3, but was delayed by constant power failures. Nerves were frayed by knowledge that thousands of tons of explosives lay in the mine levels just below. Again the lack of materials forced ingenuity upon them: this time gasproof clothing from the Army stores cushioned the Watteaus and Lancrets. The caskets were brought to the surface on V-E Day; while they worked, the men listened to news of this event on the radio. The last and heaviest coffin, which held Frederick the Great, took more than an hour to load in the elevator; as it rose slowly above ground, the strains of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” followed by “God Save the King,” rang out into the evening.

Other books

Starfish Prime (Blackfox Chronicles Book 2) by T.S. O'Neil

Everywhere That Tommy Goes by Howard K. Pollack

Aegean Intrigue by Patricia Kiyono

Obsidian Son (The Temple Chronicles Book 1) by Shayne Silvers

Lover's Gold by Kat Martin

Dark Currents by Buroker, Lindsay

Hot Decadent Rising (Breath of Darkness) by Stauffer, Candice

A Part of Me by Anouska Knight

Scarred Beauty by Sam Crescent

A Memory of Violets by Hazel Gaynor