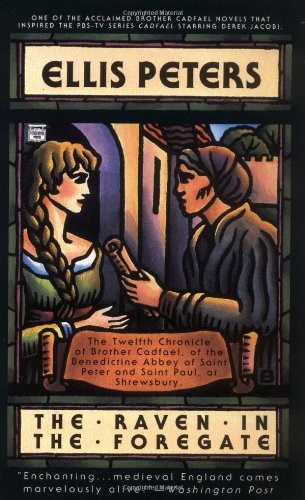

The Raven in the Foregate

Read The Raven in the Foregate Online

Authors: Ellis Peters

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #General

The Raven

in the

Foregate

The

Twelfth Chronicle of Brother Cadfael, of the Benedictine Abbey of Saint Peter

and Saint Paul, at Shrewsbury

Ellis Peters

ABBOT RADULFUS CAME TO CHAPTER, on this first day of

December, with a preoccupied and frowning face, and made short work of the

various trivialities brought up by his obedientiaries. Though a man of few

words himself, he was disposed, as a rule, to allow plenty of scope to those

who were rambling and loquacious about their requests and suggestions, but on

this day, plainly, he had more urgent matters on his mind.

“I must tell you,” he said, when he had swept the last

trifle satisfactorily into its place, “that I shall be leaving you for some

days to the care of Father Prior, to whom, I expect and require, you shall be

as obedient and helpful as you are to me. I am summoned to a council to be held

at Westminster on the seventh day of this month, by the Holy Father’s legate,

Henry of Blois, bishop of Winchester. I shall return as soon as I can, but in

my absence I desire you will make your prayers for a spirit of wisdom and

reconciliation in this meeting of prelates, for the sake of the peace of this

land.”

His voice was dry and calm to the point of

resignation. For the past four years there had been precious little inclination

to reconciliation in England between the warring rivals for the crown, and no

very considerable wisdom shown on either side. But it was the business of the

Church to continue to strive, and if possible to hope, even when the affairs of

the land seemed to have reverted to the very same point where the civil war had

begun, to repeat the whole unprofitable cycle all over again.

“I am well aware there are matters outstanding here,”

said the abbot, “which equally require our attention, but they must wait for my

return. In particular there is the question of a successor to Father Adam,

lately vicar of this parish of Holy Cross, whose loss we are still lamenting.

The advowson rests with this house. Father Adam has been for many years a much

valued associate with us here in the worship of God and the cure of souls, and

his replacement is a matter for both thought and prayer. Until my return,

Father Prior will direct the parish services as he thinks fit, and all of you

will be at his bidding.”

He swept one long, dark glance round the chapter

house, accepted the general silence as understanding and consent, and rose.

“This chapter is concluded.”

“Well, at least if he leaves tomorrow he has good

weather for the ride,” said Hugh Beringar, looking out from the open door of

Brother Cadfael’s workshop in the herb garden over grass still green, and a few

surviving roses, grown tall and spindly by now but still budding bravely.

December of this year of Our Lord 1141 had come in with soft-stepping care,

gentle winds and lightly veiled skies, treading on tiptoe. “Like all those

shifting souls who turned to the Empress when she was in her glory,” said Hugh,

grinning, “and are now put to it to keep well out of sight while they turn

again. There must be a good many holding their breath and making themselves

small just now.”

“Bad luck for his reverence the papal legate,” said

Cadfael, “who cannot make himself small or go unregarded, whatever he does. His

turning has to be done in broad daylight, with every eye on him. And twice in

one year is too much to ask of any man.”

“Ah, but in the name of the Church, Cadfael, in the

name of the Church! It’s not the man who turns, it’s the representative of Pope

and Church, who must preserve the infallibility of both at all costs.”

Twice in one year, indeed, had Henry of Blois summoned

his bishops and abbots to a legatine council, once in Winchester on the seventh

of April to justify his endorsement of the Empress Maud as ruler, when she was

in the ascendant and had her rival King Stephen securely in prison in Bristol,

and now at Westminster on the seventh of December to justify his swing back to

Stephen, now that the King was free again, and the city of London had put a

decisive end to Maud’s bid to establish herself in the capital, and get her

hands at last on the crown.

“If his head is not going round by now, it should be,”

said Cadfael, shaking his own grizzled brown tonsure in mingled admiration and

deprecation. “How many spins does this make? First he swore allegiance to the

lady, when her father died without a male heir, then he accepted his brother

Stephen’s seizure of power in her absence, thirdly, when Stephen’s star is

darkened he makes his peace—a peace of sorts, at any rate!—with the lady, and

justifies it by saying that Stephen has flouted and aggrieved Holy Church… Now

must he turn the same argument about, and accuse the Empress, or has he

something new in his scrip?”

“What is there new to be said?’ asked Hugh, shrugging.

“No, he’ll wring the last drop from his stewardship of Holy Church, and make

the best of it that every soul there will have heard it all before, no longer

ago than last April. And it will convince Stephen no more than it did Maud, but

he’ll let it pass with only a mild snarl or two, since he can no more afford to

reject the backing of Henry of Blois than could Maud in her day. And the bishop

will grit his teeth and stare his clerics in the eyes, and swallow his gall

with a brazen face.”

“It may well be the last time he has to turn

about-face,” said Cadfael, feeding his brazier with a few judiciously placed

turves, to keep it burning with a slow and tempered heat. “She has thrown away

what’s likely to be her only chance.”

A strange woman she had proved, King Henry’s royal

daughter. Married in childhood to the Holy Roman Emperor Henry V, she had so

firmly ingratiated herself with her husband’s people in Germany that when she

was recalled to England, after his death, the populace had risen in

consternation and grief to plead with her to stay. Yet here at home, when fate

threw her enemy into her hands and held the crown suspended over her head, she

had behaved with such vengeful arrogance, and exacted such penalties for past

affronts, that the men of her capital city had risen just as indignantly, not

to appeal to her to remain, but to drive her out and put a violent end to her

hopes of ever becoming their ruler. And it was common knowledge that though she

could turn even upon her own best allies with venom, yet she could also retain

the love and loyalty of the best of the baronage. There was not a man of the

first rank on Stephen’s side to match the quality of her half-brother, Earl

Robert of Gloucester, or her champion and reputed lover, Brian FitzCount, her

easternmost paladin in his fortress at Wallingford. But it would take more than

a couple of heroes to redeem her cause now. She had been forced to surrender

her royal prisoner in exchange for her half-brother, without whom she could not

hope to achieve anything. And here was England back to the beginning, with all

to do again. For if she could not win, neither could she give up.

“From here where I stand now,” said Cadfael,

pondering, “these things seem strangely distant and unreal. If I had not been

forty years in the world and among the armies myself, I doubt if I could

believe in the times we live in but as a disturbed dream.”

“They are not so to Abbot Radulfus,” said Hugh with

unwonted gravity. He turned his back upon the mild, moist prospect of the

garden, sinking gently into its winter sleep, and sat down on the wooden bench

against the timber wall. The small glow of the brazier, damped under the turf,

burned on the bold, slender bones of his cheeks and jaw and brows, conjuring

them out of deep shadows, and sparkling briefly in his black eyes before the

lids and dark lashes quenched the sparks. “That man would make a better adviser

to kings than most that cluster round Stephen now he’s free again. But he would

not tell them what they want to hear, and they’d all stop their ears.”

“What’s the news of King Stephen now? How has he borne

this year of captivity? Is he likely to come out of it fighting, or has it

dimmed his ardour? What is he likely to do next?”

“That I may be better able to answer after Christmas,”

said Hugh. “They say he’s in good health. But she put him in chains, and that

even he is not likely to forgive too readily. He’s come out leaner and hungrier

than he went in, and a gnaw in the belly may well serve to concentrate the

mind. He was ever a man to begin a campaign or siege all fire the first day,

weary of it if he got no gain by the third, and go off after another prey by

the fifth. Maybe now he’s learned to keep an unwavering eye fixed on one target

until he fetches it down. Sometimes I wonder why we follow him, and never look

round, then I see him roaring into personal battle as he did at Lincoln, and I

know the reason well enough. Even when he has the woman as good as in his

hands, as when she first landed at Arundel, and gives her an escort to her

brother’s fortress instead of having the good sense to seize her, I curse him

for a fool, but I love him while I’m cursing him. What monumental folly of

mistaken chivalry he’ll commit next, only God knows. But I’ll welcome the

chance to see him again, and try to guess at his mind. For I’m bidden forth,

Cadfael, like the abbot. King Stephen means to keep Christmas at Canterbury

this year, and put on his crown again, for all to see which of two heads is the

anointed monarch here. And he’s called all his sheriffs to attend him and

render account of their shires. Me among the rest, seeing we have here no properly

appointed sheriff to render account.”

He looked up with a dark, sidelong smile into

Cadfael’s attentive and thoughtful face. “A very sound move. He needs to know

what measure of loyalty he has to rely on, after a year in prison, or close on

a year. But there’s no denying it may bring me a fall.”

For Cadfael it was a new and jolting thought. Hugh had

stepped into the office of sheriff perforce, when his superior, Gilbert

Prestcote, had died of his battle wounds and the act of a desperate man, at a

time when the King was already a prisoner in Bristol castle, with no power to

appoint or to demote any officer in any shire. And Hugh had served him and

maintained his peace here without authority, and deserved well of him. But now

that he was free to make and break again, would Stephen confirm so young and so

minor a nobleman in office, or use the appointment to flatter and bind to

himself some baron of the march?

“Folly!” said Cadfael firmly. “The man is a fool only

towards himself. He made you deputy to his man out of nowhere, when he saw your

mettle. What does Aline say of it?”

Hugh could not hear his wife’s name spoken without a

wild, warm softening of his sharp, subtle face, nor could Cadfael speak it

without relaxing every solemnity into a smile. He had witnessed their courtship

and their marriage, and was godfather to their son, two years old this coming

Christmastide. Aline’s girlish, flaxen gentleness had grown into a golden,

matronly calm to which they both turned in every need.

“Aline says that she has no great confidence in the

gratitude of princes, but that Stephen has the right to choose his own

officers, wisely or foolishly.”

“And you?” said Cadfael.

“Why, if he gives me his countenance and writ I’ll go

on keeping all his borders for him, and if not, then I’ll go back to Maesbury

and keep the north, at least, against Chester, if the earl tries again to

enlarge his palatinate. And Stephen’s man must take charge of west, east and

south. And you, old friend, must pay a visit or two over Christmas, while I’m

away, and keep Aline company.”