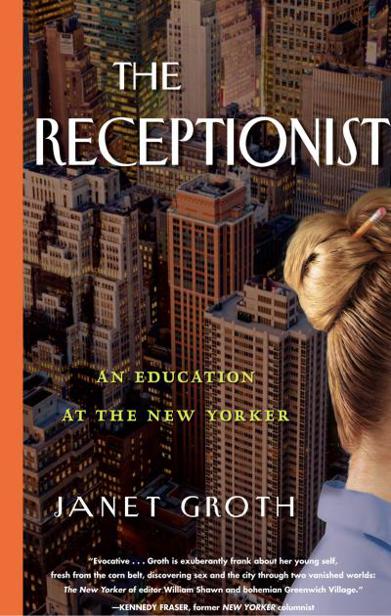

The Receptionist

Authors: Janet Groth

THE RECEPTIONIST

An Education at

T

he New Yorker

JANET GROTH

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL | 2012

Janet Groth in 1962.

PHOTO CREDIT: KEVIN WALLACE

I

NTRODUCTION;

OR,

J

ACK

S

PILLS

THE

B

EANS

I

T ALL HAPPENED BY

the merest chance. Or perhaps the heavens

were

aligned. In August 1957 I finished my BA degree at the University of Minnesota. At the same time I received a phone call telling me of some upcoming excitement in the area—a manned balloon flight into the stratosphere was being filmed for a CBS science show.

Th

inking that it would advance my dream of seeking fame and fortune as a writer, I managed to secure a temporary job as assistant to Arthur Zegart, the show’s writer-director. It went well, and Mr. Zegart invited me to send him a copy of my résumé should I decide to come to New York. He received it three weeks later while fishing in Maine with his friend E. B. White and promptly arranged an interview for me when Mr. White returned to his office at

Th

e New Yorker.

E. B. White was then one of the best-known writers on the magazine, but his shyness, I found out later, was of mythic proportions, and this interview quite unprecedented. He seemed pained to be in the presence of anyone at all, much less a corn-fed girl from Iowa who was looking for a job.

“What sort of work do you envision doing, Miss Groth?” His handsome, fine-featured gray head was lowered, his eyes cast down, his voice little above a whisper. I was overwhelmed with a desire to put the poor man at ease.

“Well, I want eventually to write, of course, but I would be glad to do anything in the publishing field.”

Mr. White took a moment to absorb this information. When he could bring himself to speak again, he asked, “Can you type?”

“Not at a professional level,” I said.

He coughed and looked at the résumé that Arthur Zegart had given him and that had led to my being there in his office. “What about this short story prize you won?

Th

is Anna Augusta Von Helmholtz Phelan prize,” he said. “Was that story typed?”

I told him that yes, of course it had been, but that I deliberately maintained a slow, self-devised system that involved looking at the keyboard.

“I was afraid, you see, that if I became a skilled typist, I would wind up in an office typing pool.”

For the first time Mr. White looked directly at me. “And you don’t want to wind up there?” he asked.

I suspected that he had some sympathy for the course I had taken.

“No, I think anything would be more interesting to me than that,” I said. How rash and how fateful that course turned out to be!

After a few more questions, Mr. White concluded the interview by calling into his office Miss Daise Terry. I later found out she was a formidable figure around the magazine, its manager in charge of secretarial personnel. A petite woman of four feet nine or ten, no more than five feet, even in inch-and-a-half heels, she had a cap of tightly curled white hair and a slash of geranium-pink lipstick in a face dominated by piercing blue eyes. At perhaps sixty or so, she needed no glasses.

Handing her my résumé, White said, “Miss Groth is looking for a job here at the magazine but would rather not be in the typing pool. Will you see if there is anything you can do for her?”

“I will,” she said, asking me to come with her.

I learned that she, too, was from the middle of the country, having left her native Kansas in 1918 to join the International Red Cross, and had wound up in New York after some years serving in Vienna.

She said, “Now, as a midwesterner, you have better sense than the Westchester County and Connecticut girls who come through this office. I always have to take them in hand and give them a stern talking-to about their behavior and conduct. We want ladylike clothing and ladylike behavior at all times.”

She cast her eyes over my black linen dress and black pumps. “I see I needn’t tell you that. I always think the best place to shop for the kind of thing we like to see is at Peck and Peck.”

I said I would keep that in mind.

“At the moment,” she said, “we have an opening at the reception desk down on eighteen—that’s the writers’ floor.

Th

ere is not much traffic there, but the editor or two and the half-dozen writers whose offices are down there need someone to look after their mail and messages. Do you think that would appeal to you?”

I said that sounded fine.

“Good,” she said. “You may report in to me for work on Monday morning at ten.”

We shook hands, and I was officially a member of the editorial staff.

So that is how I got my “in” at

Th

e

New Yorker

—as they always say, it’s not who you are but who you know. And so far, my story was typical, if a good deal luckier than most.

Th

ere was every reason to suppose that if I didn’t leave to marry, in the course of a year or two I would be joining the trail of countless trainees before me, moving either into the checking department or to a job as a Talk of the Town reporter, and perhaps from one of those positions to the most coveted of spots, that of a regular contributor with a drawing account.

Yet with the exception of one six-month stint in the art department, I did not rise from my initial post.

Th

e William Shawn years at

Th

e New Yorker,

1952–87, completely encompass my twenty-one years’ employment there, from 1957 to 1978. I entered the workforce before the feminist era, and as I ponder the way women in general failed to thrive in that world, how often they were used and overlooked, I recognize that I was part of a larger historical narrative. As for my personal struggles, during much of the time in question, I was undergoing a prolonged identity crisis, and the real struggle, for me, was the one that arose from my proximity to all the creative people I served. Was I or was I not “one of them”? And since I didn’t know, it is scarcely surprising that

Th

e New Yorker

didn’t know, either, what in the world to do with me.

I THOUGHT OF THE

forty or so idiosyncratic inhabitants of the eighteenth floor as “my writers” and the six or so cartoonists billeted there as “my artists.” I watered their plants, walked their dogs, boarded their cats, sat their children—and sometimes their houses—when they went away. Of course, I also took their messages. Not required in the skill set, but over the years I

received

messages, too, along with impressions, confidences, and an education in a variety of subjects. I was there, among the men and women who wrote and edited the magazine, for longer than many of them were. I watched their comings and goings, their marriages and divorces, their scandalous affairs, their failures and triumphs and tragedies and suicides and illnesses and deaths.

After leaving the magazine, I used various tactics to mask the lateral trajectory of my stay there. It was Jack Kahn (E. J. Kahn Jr., as he signed his

New Yorker

pieces) who blew my cover, all unintentionally. I’m sure he never guessed that I had been trying to keep a lid on my failure to advance at the magazine, imagining that I could hide it from the world at large as my own guilty secret.

In 1976 I taught a course at Vassar called

Th

e Contemporary Press. Jack was one of the writers from “my floor” who came up to Poughkeepsie as a guest speaker. He mentioned the event in his 1979 memoir

About the New Yorker and Me

and introduced me this way:

In many respects,

Th

e New Yorker

belies its reputation for institutional eccentricity. We have some writers and editors around who could pass for bankers and who, as they walk toward the New York Yacht Club on West Forty-fourth Street, could not unreasonably be expected by passersby to continue on inside. And yet we do have our authentic oddities. Jan Groth is surely one. She is finishing her Ph.D. dissertation in English. She has taught that subject at a high academic level. (She also writes an elegant Italian script.) But in twenty years or so she has never risen at the magazine—possibly of her own volition, though I doubt it—beyond being the eighteenth-floor receptionist, which is where she started off. We who spend many daylight hours there, mind you, are delighted with her permanence. She takes our messages when we are away from our desks, as we often are; she has learned to recognize the voices of our wives and children. As in our absences she comforts our friends, so when the occasion demands does she protect us against our enemies.

I am not sure what Jack meant by his reference to protecting him and the other writers from their enemies, but I can guess. He was endorsing my efforts to shield them from all distractions that would interfere with their work. I have more trouble with Jack’s reference to me as one of

Th

e New Yorker

’s “authentic oddities.” It’s one thing to joke to my fellow Lutherans about being an oddity as a churchgoer in a club full of secular humanists. It is quite another to find myself among

New Yorker

staffers who have been so characterized in

New Yorker

lore.

Th

ere was, for example, the brilliant fact checker Dorothy Dean, who gave off manic vibes so electric they created a people-free zone of a ten-foot radius wherever she went.

Th

ere was the magazine’s Odd Couple (one of several such), this one consisting of shambling, grumpy Frederick “Freddie” Packard, also a fact checker, and his spouse, the publication’s crackerjack grammarian Eleanor Gould. Miss Gould, a walking version of Fowler’s

Modern English Usage,

would rank high in any listing of authentic oddities, and among our numerous hypochondriacs, Freddie outcomplained a roster of champs in that department. His best moment may have come when he famously began his reply to a colleague’s routine inquiry into his health with “Well, I’ve got these two colds . . .” Freddie would have felt vindicated by a recent piece in Science Times declaring it perfectly possible to have two colds—a head cold and a sinus cold—simultaneously.

Others with colorful, weird propensities included the editor Rogers “Popsy” Whitaker—who, despite a perpetual frown, a thrust-forward lower lip, sagging suspenders, and a portly form, was inclined to pitch rose-laden woo at spoken-for damsels on the editorial staff—and the writers Maeve Brennan and St. Clair McKelway. Miss Brennan and Mr. McKelway were once young marrieds down in the Village but in their later years, split from each other, shared histories of colorful breakdowns. Miss Brennan, hoping to add height to her tiny frame, teased her red hair into a five-inch beehive, which, in her bouts of lost perspective, turned into a terrifying tangle as she forgot to give it the occasional brush. Mr. McKelway went in for crayoning the office walls periodically with shocking signs and logos that necessitated early morning scrubbings-down.

Th

e list could go on and on and include the overcoat-clad, claustrophobic editor in chief, Mr. Shawn himself. I have always loved the idea that

Th

e New Yorker

was a place with broad limits of tolerance for unusual looks and behavior, a haven for the “congenitally unemployable,” as Rogers Whitaker and A. J. Liebling are both reported to have said, but I had never thought of myself as belonging among them.

Certainly in the beginning I fit the normal profile, being one of the thousands who come to the city from the provinces and, according to E. B. White, give New York its dynamism and buzz. In

Here Is New York

he divides residents into three types.

Th

e first are the native born, the second the commuters, and the third—the source of the city’s vitality, élan, and magical “deportment”—are those who come to it from the hinterland, the ones for whom the city is their destination, “the goal.” I came as one of the third type.

What happened after I got there is a more complicated story.