The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West (11 page)

Read The Red and the White: A Family Saga of the American West Online

Authors: Andrew R. Graybill

Tags: #History, #Native American, #United States, #19th Century

A

S

N

ATHAN

C

LARKE

slipped away, momentous events were occurring some one thousand miles to the south, in Texas. The preceding October a bitter conflict had erupted there between the Mexican government and the Anglos it had invited to settle in the northern portion of their republic over the past decade and a half. At first, federal officials in Mexico City hoped that these newcomers would provide a buffer between raiding Indians on the southern Plains and residents of the Mexican interior. Yet the Anglos soon chafed under Mexican rule, especially after President Antonio López de Santa Anna attempted to exert greater control over outlying regions of the country, including the province of Coahuila y Tejas. When Mexican troops tried to seize the cannon at the small southern Texas hamlet of Gonzales on 2 October 1835, the Anglo residents drove them off, sparking the Texas Revolution.

29

Word of the conflict spread quickly to the United States and exerted an almost centripetal pull on adventuresome young men who headed off to join the fray. Many hailed from Tennessee, none more famous than Davy Crockett. The forty-nine-year-old politician and frontiersman was already celebrated as a legend in his own time, much like Buffalo Bill Cody later in the nineteenth century; both were products of relentless self-promotion and the fabrication of tall tales, but they also had legitimate ability in the outdoors. Following a defeat in his bid for reelection to the House of Representatives in 1834, Crockett allegedly told his constituents that they could “go to hell” while he went to Texas.

30

His celebrity reached untold heights when he and the approximately 180 defenders of the Alamo, a small fortified mission in the sleepy town of San Antonio, were killed by Mexican troops on 6 March 1836, following a two-week siege.

Also from the Volunteer State was Crockett’s good friend Sam Houston, former governor of Tennessee and one of Andrew Jackson’s favorite protégés. Houston had fled Nashville in 1829 following the embarrassing breakup of his short first marriage, hounded by accusations of reprobate personal conduct. After recuperating from his divorce among Cherokee friends in what is now Oklahoma, Houston made his way to Texas in 1832 and soon became involved in the Anglo struggle against Mexico. At a convention organized to declare the independence of Texas held on 2 March 1836, four days before the fall of the Alamo, Houston was named commander in chief of the Texas army. Seven weeks later “the Raven,” as the Cherokees called him, brought an unlikely but decisive end to the war by leading his ragtag troops in a rout of Santa Anna’s forces at the Battle of San Jacinto in eastern Texas.

31

As it is for most men who came to Texas during the chaotic period of the revolution and its aftermath, it is difficult to fix with certainty when and how Malcolm Clarke arrived. One thing is sure: he did not see any of the fighting, for at the time that Sam Houston’s men swarmed the battlefield at San Jacinto with their cries of “Remember the Alamo!” Clarke was finishing his second year at the USMA.

32

The first indication of his presence in Texas is a payment claim for service in the revolutionary army for a period from August to December 1837, suggesting an arrival sometime in the summer of that year.

33

This seems plausible considering that, after his expulsion, Clarke probably visited his widowed mother in Cincinnati (a good bet, given the Queen City’s location on an obvious river route from West Point to Texas), before making his way down the Mississippi to New Orleans and then across the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston.

34

Though he was twenty years old and widely traveled, nothing had prepared Malcolm Clarke for what he saw upon his arrival in the new Lone Star Republic. With the end of hostilities, most of the volunteers—heavily armed, shiftless young men—roamed the towns and countryside, and with little to do they turned to gambling, drinking, and much worse. Given this unpromising demographic, President Sam Houston and his military leaders were doubtless pleased to fill the ranks of their professional army with more-seasoned soldiers like Clarke, which perhaps explains how Clarke, despite his late appearance on the scene and total lack of combat experience, was made a captain. Though additional details of his service are unknown (for instance, which company he commanded), he was likely deployed in eastern Texas, protecting the settlements there as well as the state capital at Houston from Indians and desperadoes.

While in Texas, as if out of a scene from a novel, Clarke seems to have encountered his old West Point nemesis, Lindsay Hagler, whose tenure at the USMA had been even shorter than his own (no surprise, perhaps, given Hagler’s eighty-nine demerits during the 1834–35 school year; Clarke had less than a third that number).

35

Enlisting as a captain in the Texas army in June 1836, Hagler served through the end of the following year and spent at least some of his time recruiting for the cause in the United States. According to an account offered by Clarke’s sister Charlotte, one day the two men found themselves on the same stretch of lonely road, riding in opposite directions. Clarke, who carried two pistols, had fired earlier at a prairie hen, but could not remember which gun he had discharged. Not wanting Hagler to see him fumbling with his weapon, a sure sign of cowardice, Clarke simply placed his hand on one of the revolvers and stared coolly at his enemy. The two passed each other without a word, though Clarke tensed in anticipation of a shot to the back (he expected nothing less from the craven southerner). Hagler remained in Texas and later served three terms in the state’s house of representatives, but died in 1846 during a street brawl in the small town of Goliad.

36

Clarke, however, did not linger in Texas. After mustering out of the army in December 1837, he signed on for a short stint as a private in the Houston Volunteer Guards, a unit composed mostly of outlaws under the command of Reuben Ross, a veteran of the Texas Revolution. Although his military service made him eligible for a land grant in the new republic, by the end of 1838 Clarke had returned to the United States, having determined to fulfill his father’s wish that he obtain a commission in the U.S. Army.

37

With the help of a Missouri congressman named John Miller (who may have taken an interest in Malcolm’s case because, like Nathan Clarke, Miller was a veteran of the War of 1812), Malcolm received an invitation to interview with the army’s board of examiners. Before such a meeting could take place, however, Secretary of War Joel Poinsett wrote Miller an apologetic note on 31 December 1838 to explain that it was all a mistake: Clarke’s expulsion from West Point rendered him ineligible for further service.

38

As the New Year began, Malcolm Clarke surveyed the wreckage of his life: no job, no property, not even a family of his own. Like Sam Houston and Davy Crockett before him, he looked to the West for a new start, but this time he set his sights far beyond Texas.

To the Upper Missouri

In 1843 the painter and naturalist John James Audubon traveled up the Missouri River with his eldest son, Victor, for research that led ultimately to his final published work,

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America.

Having just issued the octavo edition of his celebrated

Birds of America

the year before, the fifty-eight-year-old Audubon was at the height of his fame, renowned throughout Europe and the United States for the precision and beauty of his work. With dark eyes, flowing gray hair, and a matted beard, Audubon looked every bit the quintessential U.S. frontiersman. He thus fit in nicely at Fort Union when he and his party arrived in June. Alexander Culbertson gave them a warm welcome there. Over the next two months, the artist hunted, sketched, and even executed portraits of Culbertson and his wife, Natawista, all of which he meticulously described in his journal.

Fort Union and its environs fascinated Audubon; one day in mid-July proved particularly memorable. Following an afternoon meal, the painter watched from the fort as the Culbertsons and several others—including Owen McKenzie, son of the post’s legendary former bourgeois, and Lewis Squires, Audubon’s New York neighbor and personal secretary—put on Indian dress and rode out onto the prairie. The riders thrilled the audience with a show of equestrian skill, which ended abruptly when a “fine Wolf” trotted into view. All at once, the mounted party gave chase to the animal, each member hoping to claim it as a trophy. Though a crack shot with a gun, McKenzie let fly with an arrow instead and missed, but Culbertson overtook the terrified creature and dropped it with a blast from his musket. The group then ran their horses at full gallop all the way back to the gates of the fort, despite the blazing summer heat. While Audubon was pleased that Squires had held his own with the others, he confessed to his journal that the paint Natawista had applied to his assistant’s face gave him the appearance of “a being from the infernal regions.”

39

This was the world Malcolm Clarke discovered when he came upriver in 1841, and it is easy to see how it captivated him so much that he stayed on the Upper Missouri for the next three decades. One associate observed, “This wild and reckless life was suited to his nature. It afforded ample scope for the exercise of all his resources.”

40

Moreover, as the friendly but zealous competition between Culbertson and McKenzie suggests, the region was one where men (and even the occasional woman, like Natawista) could prove themselves against each other in sport and sometimes more lethal contests. Most of all, the Upper Missouri gave Malcolm Clarke an opportunity to reinvent himself, to cast off the fetters of eastern society and its stifling social expectations, just as Lewis Squires had done, metaphorically at least, when he went native for an afternoon.

Clarke arrived in the region under circumstances different from Audubon’s in virtually every respect. Whereas the eminent painter came seeking inspiration for a grand project, Clarke traveled to the far West as a last resort. Unable to find work in Cincinnati “congenial to his taste,” he applied one final time in the spring of 1841 for a position in the army. The answer from the Department of War was unequivocal: “Having had one opportunity of entering the Service of the Country, and forfeited it by your own indiscretion, it could not be considered other than an act of impropriety to other meritorious applicants were your claims now preferred to theirs.”

41

In the wake of this disappointment, he turned to one of his father’s old military friends, John Craighead Culbertson, who recommended Malcolm to his nephew Alexander for a position in the AFC. Later that year, probably in the summer and surely no later than the fall when the rivers froze over, Clarke made his first appearance on the Upper Missouri.

42

By contrast with his less refined colleagues in the fur trade, who were mostly uneducated and also renowned for their liquor-fueled unruliness, Clarke had enjoyed a relatively sophisticated upbringing. Distinguished by his stint at West Point, which he rarely failed to mention, Clarke used his background to earn himself useful social capital among the trappers and traders in the AFC. And yet it was his association with Alexander Culbertson that proved definitive. In this respect, the timing of Clarke’s arrival was perfect, for just the year before, in 1840, Pierre Chouteau had promoted Culbertson by offering him charge of Forts Union and McKenzie, making the benevolent Pennsylvanian one of the company’s most powerful representatives in fur country. Whether he perceived Clarke’s abilities right away or merely acceded to the entreaties of his beloved uncle, Culbertson received the newcomer as an apprentice and installed him as a clerk at Fort McKenzie.

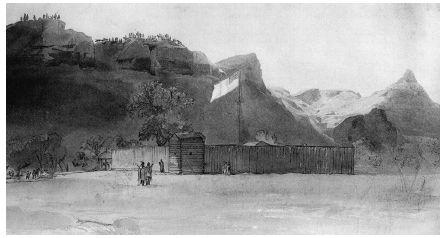

Karl Bodmer,

Sketch of Fort McKenzie

, ca. 1833. Malcolm Clarke worked at Fort McKenzie for much of his first decade on the Upper Missouri, and it was there that he was most likely married to Coth-co-co-na in 1844. Courtesy of the Overholser Historical Research Center, Fort Benton, Montana.

At the time of Clarke’s arrival, Fort McKenzie was almost ten years old and still one of the AFC’s most productive outposts. Yet it was not quite so grand an edifice as Fort Union. Prince Maximilian of Wied, the German who had visited the fort in 1833, derided McKenzie’s construction as “crude and very flimsy.” That perhaps reflects the time constraints under which it was assembled and especially the understanding that the Piegans might tire of its presence at any time and put it to the torch, a fact that militated against architectural embellishments. Nevertheless, the fort’s setting was spectacular: near the confluence of the Marias and Missouri Rivers, opposite an imposing wall of dark bluffs soaring two hundred feet high.

43