The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (15 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

Left to right: Reinhard Pitsch, Othmar Keplinger, and Thomas Gratt.

Gratt and Keplinger's bad luck at the border would be repeated on December 20, as Gabriele Kröcher-Tiedemann attempted to cross into Switzerland, accompanied by Christian Möller. They were both captured and found to be in possession of weapons, phony IDs, and money from the Palmers actionâbut not before Kröcher-Tiedemann had seriously wounded two border guards.

40

(Three weeks later, a grenade went off in the Bern office of the prosecutor responsible for this case. The action was claimed by a Benno Ohnesorg Commando, which promised further attacks if the two were extradited from Switzerland to the FRG.)

41

This left Inge Viett as one of the most senior 2JM combatants on the street. Over the next years, she would play an important part in determining the course of the West German guerilla; not only the 2JM, but the RAF as well.

Born in 1944, Viett had been one of the millions of European children orphaned in the chaos of the war and its aftermath. Taken in by

a family in Schleswig-Holstein, from a young age it was clear that her function was to provide manual labor, her status little different from that of a farm animal. Sleeping on a bed of hay (shared with her foster-sister) in the same annex where pigs were butchered, her childhood as recounted in her autobiography reads like an unhappy Dickens novel, replete with deprivation and abuse.

42

Leaving this “home” in her late teens, she traveled widely, and would later credit time she spent in North Africa for her political awakening.

43

Upon returning to the FRG, Viett joined the APO, where she met other radical women, including Verena Becker, with whom she would go on nighttime excursions smashing the windows of sex shops and bridal stores.

44

Both women would be recruited into the 2JM. Becker was arrested in 1972, at the age of nineteen, and charged in connection with the bombing of the British Yacht Club in West Berlin,

45

for which she received a six-year sentence, only to be subsequently freed in the 1975 Lorenz exchange, at which point she switched over to the RAF. As we have seen, she would next be arrested in 1977, along with Günter Sonnenberg, in the town of Singen.

Meanwhile, Viett remained with the 2JM, but by 1976 she too had become a strong proponent of rapprochement with the RAF.

This new direction was pushed forward by the sad reality that even the vibrant West Berlin scene was not able to shelter the guerilla from repression, and by the fact that several members of the 2JM were essentially living with RAF combatants in the PFLP (EO)'s Middle East camps.

46

The political and logistical pressures that resulted from the RAF's German Autumn simply accelerated this process, and behind the scenes the 2JM would effectively split into two factions, the one “social revolutionary” (or “populist” to its detractors), the other “anti-imperialist.”

The anti-imperialist position that would attract so many radicals of the APO generation was always most closely identified with the RAF of the 1970s. Knut Folkerts would explain the group's position as follows:

Our assessment was that anyone who based an analysis on the conditions in the metropole, developing a worldview from that perspective, could not arrive at a valid appraisal of the situation. One must start from global conditions, or one can only arrive at the chauvinistic perspective of the relatively privileged.

1

Criticisms that the RAF ignored “domestic” contradictions due to this “global” focus are overly simplistic, and ignore the effort the RAF devoted to integrating both realities into a comprehensive critique. In this regard, it is worth highlighting these comments by Brigitte Mohnhaupt about anti-imperialism, internationalism, and social revolution:

Given that they address the same thing, these concepts cannot be placed in contradiction to one anotherâotherwise they become a caricature of themselves: internationalism reduced to appeals for solidarity with revolution somewhere else, so the question of whether people want revolution for themselves doesn't raise its ugly head; anti-imperialism as research into imperialism, where the abstractions fail to address the practical question of how to resist it; social revolution as a synonym for social questions that must be addressed to meet people's needs, which can only end in reformism so long as the key question is ignored, namely what power relations need to be destroyed for people around the world to have their needs met. This approach only blocks any learning process or practice that could lead to a united attack.

2

_____________

1

Knut Folkerts interviewed by Vogel, “Im Politik-Fetisch wird sich nichts Emanzipatives bewegen lassen.”

It must be kept in mind that despite the terms used to describe these two political camps, everyone involved would have welcomed a social revolution, just as they all were opposed to imperialism. In the context of the West German far left, in no small part due to the influence of the

RAF, “anti-imperialism” represented an identification with the Third World national liberation struggles and translated into a deep pessimism about the short-term prospects for mass revolutionary movements in the metropole. In its extreme form, such anti-imperialism could lead to the view that the guerilla in the metropole should merge with or act under the leadership of Third World revolutionaries abroad. (While the RAF never held such a position, as we shall see, certain combatants from the Revolutionary Cells explored this strategy with tragic results.)

To be a social revolutionary, on the other hand, meant to prioritize seeking a base and a field of political action within one's own societyâthis was the view that some critics would accuse the RAF of having repudiated with its 1972 document

Black September.

Social revolutionary politics had defined the 2JM for years, but in the aftermath of the 1975 Lorenz kidnapping it had come to be rejected by increasing numbers of 2JM fighters outside of prison.

47

Within the 2JM, this split would finally be consummated during the group's 1978 trial, in which Ralf Reinders, Fritz Teufel, Ronald Fritzsch, Gerald Klöpper, Andreas Vogel, and Till Meyer faced charges related to the Drenkmann killing and Lorenz kidnapping. Presiding was Judge Friedrich Geus, well-known to the sixties generation for having acquitted killer cop Karl-Heinz Kurras of the June 2, 1967, shooting death of Benno Ohnesorgâthe very murder from which the 2JM had taken its name. While the accused maintained their innocence, they were equally outspoken in their support for armed struggle and revolutionary politics in the FRG, no matter how differently they may have come to conceive of these.

This was the context in which the anti-imperialist faction made its move, carrying out what one newspaper described as “the first serious action by proponents of âarmed struggle' since Stammheim and Mogadishu.”

48

As reported by UPI:

Two women terrorists posing as lawyers invaded an “escape-proof” jail Saturday, freed one of Germany's most wanted men and casually strolled out with him under the noses of patrolling police.

One police guard taken hostage in the meticulously planned raid at the Moabit prison was shot in the leg. The terrorists all escaped unharmedâ¦

[T]he two women used lawyers' identity cards to get into the prison and timed their raid to coincide with visits by Meyer's and Vogel's real lawyers.

Once inside, the women pulled out pistols and shouted to Meyer and Vogel to leave the unlocked cells where they were conferring with their lawyers. Meyer ran free but a guard grabbed a pistol from one of the two women and locked himself in the cell with Vogel. He sounded an alarm that alerted guards in the prison but not the police patrols outside.

The two women then took another guard hostage and forced other guards to open a security door that led to an unguarded front door.

“To show they meant business they shot their captive in the leg,” [Minister of Justice Jürgen] Baumann said.

The plot was so carefully planned and prison controls so lax that the two young women then simply strolled out of the prison's main entrance onto a busy thoroughfare under the eyes of police patrols, got into a Volkswagen bus with waiting accomplices and drove off.

The bus later was found abandoned not far from the prison. The prison had been billed as “escape proof” after undergoing a $2 million renovation.

49

The entire operation, from the time the women arrived at the prison to the time they left, took only six minutes. Almost immediately, police swarmed over the scene, soon locating the minivan, abandoned, a half-mile awayâbut the guerillas were all long gone. Certainly unknown to the raiders, the action was all the more galling for the state, as Baumann, who had replaced Oxfort as West Berlin's justice minister, had scheduled a visit that morning with his colleague from Baden-Württemberg, to show off “one of the most secure prisons in Europe.”

50

Just as his predecessor had been forced to resign following the guerilla women's breakout in 1976, Baumann too would feel compelled to step down after the 1978 jailbreak.

51

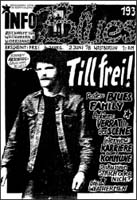

A West Berlin movement publication celebrates the Till Meyer jailbreak.

The Meyer liberation action established the predominance of the anti-imperialist faction. Not only was it carried out over fears of being perceived as the work of a “free-the-guerilla guerilla” (like the RAF), the unavoidable profile of such an action was sure to bring more heat down on the West Berlin scene, making it even more difficult for those who hoped to pursue a social revolutionary strategy. What's more, the group that carried out the action styled itself the “Nabil Harb Commando,” honoring one of the PFLP (EO) fighters who had died in Mogadishu

52

âthis despite the fact that the “populist” 2JM and its traditional supporters had been highly critical of skyjackings, which they rejected as inhumane.

53

As Gabriele Rollnik would later explain:

There were other political prisoners in Moabit, but we decided upon Till Meyer and Andreas Vogel, because they both agreed with our politics. The other men had criticized us, saying we had broken with the old 2JM. Communication with them was very difficult or had ceased altogether. They thought what we were doing was completely incorrect. They didn't understand why we weren't carrying out social revolutionary actions in Berlin any more. For us, the struggle had reached a new stage and had to be carried out taking into account the international context. Till Meyer and Andreas Vogel agreed with this decision, so they were the object of our liberation action.

54

According to Klaus Viehmann, the Meyer liberation was in fact the proverbial straw that broke the camel's back, splitting the organization and prompting Viehmann himself to leave. He was arrested just one week later, driving a car that the Nabil Harb Commando had left him. As he has explained, this was the result of a double slip-up: his erstwhile comrades hadn't told him the car was stolen, and he hadn't thought to ask. He would eventually be convicted of participation in the Meyer

liberation, the Palmers kidnapping, and a series of bank robberies, and would spend a total of fifteen years in prison, much of it in isolation.

55

As for Meyer and the women from the Nabil Harb Commando, they split up, seeking shelter in various East Bloc countries, with the intention of regrouping in the Middle East. A misjudgment, as the guerilla's relationship to the world of “real existing socialism” remained ambiguous in this period, just weeks after the RAF's Zagreb arrests. As such, one month after the breakout, on June 21, Meyer was recaptured, along with Rollnik, Gudrun Stürmer, and Angelika Goder, at the Golden Beach holiday resort in Bulgaria.