The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (21 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

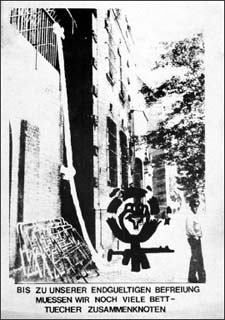

Poster from the late 1970s: “Until we are finally free, we will have to tie many sheets together.”

_____________

1

. Christian Joppke,

Mobilizing Against Nuclear Energy: A Comparison of Germany and the United States

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 39. This chapter relies heavily on Joppke's account, which is one of the better studies of the ebbs and flows of the antinuclear movement in the 1970s and â80s.

2

. Dorothy Nelkin and Michael Pollak,

The Atom Besieged: Antinuclear Movements in France and Germany

(Boston: MIT Press, 1982), 22.

3

. Joppke, 93.

4

. Ibid., 94.

5

. Ibid., 93.

6

. Ibid., 94.

7

. Ibid., 117.

8

. Along with the women's movement, the

Spontis,

K-groups, and Citizens Initiatives comprised the main strains of the West German left in the 1970s. For more on this, see Moncourt and Smith Vol. 1, 433-436, 441-452.

9

. Joppke, 104.

10

. Ibid., 97-98.

11

. John Vinocur, Associated Press “Little Towns Get Big Results,”

The Greeley Daily Tribune,

March 6, 1975.

12

. United Press International, “Demonstrators Again Take Over A-Plant Site,”

The Independent

(Long Beach, CA), February 25, 1975.

13

. Ruud Koopmans, “The Dynamics of Protest Waves: West Germany, 1965 to 1989,”

American Sociological Review

58, no. 5 (October 1993): 653.

14

. Joppke, 101.

15

. Ibid.

16

. Ibid., 102.

17

. Andrei S. Markovits and Philip S. Gorski,

The German Left: Red, Green and Beyond

(New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 103-104.

18

. Joppke, 103.

19

. Geronimo,

Fire and Flames: A History of the German Autonomist Movement

(Oakland: PM Press, 2012), 86.

20

. Despite its name,

Autonomie

predated the German

Autonomen

by several years. Founded in 1975, it would provide “a historical bridge from the 1968 student revolt to the autonomous scene of the 1980s.” Geronimo, 63-66.

21

. Joppke, 106. Readers may have noticed that nary a year passed in the Federal Republic at this time without some demonstration or riot being described by someone, somewhere, as “the worst political violence ever” in the country. This is not just testimony to the steady escalation of social conflict that followed the 1960s, but also to the temptation (widespread among writers) to always frame matters in terms of extremes.

22

. Ibid., 105. The state would try for several years to apply the

Berufsverbot

âa law that banned suspected radicals from working in the public sectorâto remove Scheer from his university position. Finally in 1980, by which time the KPD had already been dissolved, he was “merely” fined. (Brian Martin, “Nuclear Suppression,”

Science and Public Policy

13, no. 6, December 1986: 312-320.)

23

.

WISE,

“First Anti-Nuke Activists Seek Political Asylum,” no. 5 (May-June 1979): 7.

24

. Sonja Suder and Christian Gauder, interviewed by Andreas Fanizadeh, “Du schaust immer, ob jemand hinter dir ist,”

taz,

March 20, 2010; Klaus Viehmann, “Stadtguerilla und Klassenkampfârevised,” in: jour fixe initiative berlin (ed.),

Klassen und Kämpfe

(Münster: Unrast, 2006), 71-92.

25

. Revolutionäre Zellen,

Subversiver Kampf in der Anti- AKW- Bewegung

(anonymous: np, 1980).

26

. Robert Reid, Associated Press “Anti-Nuclear Demonstration in West Germany Peaceful,”

The Joplin Globe

(Joplin, Missouri), September 26, 1977.

27

. Peter Francis, “Tu-wat (Do Something),”

Open Road

no. 13, Spring 1982.

28

. Reid, “Anti-Nuclear Demonstration in West Germany Peaceful.”

29

. Joppke, 108.

30

. Open Road, “German War Machine Targets Anti-Nukers,” no. 11, Summer 1980: 18.

31

. Geronimo, 71-72.

32

. Sabine Von Dirke,

All Power to the Imagination! The West German Counterculture from the Student Movement to the Greens

(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1997), 111-112.

33

. Wikipedia, “Tunix Kongress.”

34

. Geronimo, 73.

35

. Ibid., 74.

36

. Von Dirke, 120.

37

. Ibid.

38

. Michael Sontheimer, interviewed by Rainer Berthold Schossig, “25 Jahre taz,”

Deutschlandradio

[online], April 12, 2004.

39

. Keith Duane Alexander, “From Red to Green in the Island City: The Alternative Liste West Berlin and the Evolution of the West German Left, 1945-1990,” dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, 2003: 147.

40

. Ibid., 145.

41

. Having distanced himself from the guerilla, while on trial with the others from the 2JM Klöpper was actually elected on the AL ticketâwhich did not stop him from receiving a sentence of over 11 years in prison. “Eine seltsame Würze. Darf ein mutmaÃlicher Terrorist ins Parlament?”

Die Zeit,

May 25, 1981.

42

. Alexander, 150. Schily would return to AL, briefly, in 1981 (ibid., 190).

43

. Isabelle De Pommereau, “How Germany's Greens rose from radical fringe to ruling power,”

Christian Science Monitor,

March 28, 2011.

44

. Alexander, 181.

45

. For more on the women's liberation movement in this period, see Moncourt and Smith Vol. 1, 444-448.

46

. Untitled document about the West German women's movement, in the editors' possession, 1980s.

47

. Wikipedia [website], “International Tribunal on Crimes against Women.”

48

. This was roughly equivalent to the “Take Back the Night” phenomenon in North America, which was itself another result of the Brussels conference.

49

. Georgy Katsiaficas,

The Subversion of Politics: European Autonomous Social Movements and the Decolonization of Everyday Life

(Oakland: AK Press, 2006), 75-79.

50

. Rote Zora, “Unsere Anfänge als autonome Frauengruppe.”

51

. Katsiaficas, 77.

52

. Ibid., 78-79.

53

. Rote Zora, “Unsere Anfänge als autonome Frauengruppe.”

54

. Alexandra Michel,

Frauen, die kämpfen, sind Frauen, die leben

(Zurich: self-published, 1988), 78.

55

. According to some observers, here too the experiences of â77 were central. Wolfgang Kraushaar, for instance, has argued that “it appears to be anything but a coincidence that simultaneous with the unquestionable disaster of 1977, the radical left began a process of transformation that resulted in increased parliamentary power for the Green Party.” (Wolfgang Kraushaar,

Die RAF und der linke Terrorismus

[Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2006], 26).

Kick at the Darkness

F

IGHTERS IN THE FIELD MAY

withdraw; things are more complicated for captured combatants. In Western Europe's high-security isolation cells, the RAF prisoners continued to be targeted for destruction.

After a short time in the hospital following the attempt on her life, Irmgard Möller was back in Stammheim. Even before the harrowing events of 1977, she had been diagnosed with serious emotional, intellectual, and nervous disorders, described by court-appointed doctors as the classic symptoms of sensory deprivation.

1

Rather than heed recommendations that she be released from isolation, the prison authorities now had the door to her cell replaced with bars, and stationed a guard outside so that she could be kept under constant observation. She was forced to undress completely several times a day. Newspapers she received were censored, with anything even remotely related to the German Autumn cut out. Any visits she received took place through a glass partition.

2

In a fight for her life, Möller went on hunger strike, demanding association with Verena Becker.

Similarly, on February 1, 1978, Knut Folkerts, Gert Schneider, and Christof Wackernagel, who were in prison in Holland, went on hunger strike demanding an end to isolation and the visitor ban, free access to reading materials, and safe passage to a country of their choosing. The three received support from the Dutch lawyer Pieter Bakker Schut, who had been an important figure in the IVK and other prisoner support efforts since 1974,

3

as well as from the

Rood Verzetsfront

âthe RVF, or Red Resistance Frontâa Dutch Marxist-Leninist group that despite remaining aboveground shared much of the RAF's politics. (The RVF's ranks had recently been replenished by a new generation of activists, many of whom had been radicalized by the events of 1977 and the continental search for Schleyer's kidnappers.)

4

Meanwhile, an autonomous group in Belgium occupied the Dutch embassy in that country to break through the media's silence and support the prisoners' demands. While this first prisoners' strike, and the support it received, succeeded in winning some modest improvements, when a second strike was begun in October 1978, the Dutch state secretary of justice moved to quickly have the three extradited to the FRG.

5

In mid-March 1978, the RAF prisoners began their sixth collective hunger strike, demanding that they receive treatment in accord with the Geneva Convention, association, an end to the psychological warfare against the guerilla, and the release of information regarding the Stammheim deaths. As communication was extremely difficult, not everybody began on the same date, the first starting on March 10, followed by others as the word spread.

Dozens of prisoners in the FRG would participate in the strike, including some from the aboveground left and Andreas Vogel and Till Meyer of the 2JM's anti-imperialist wing.

6

Still, there was an effective media blackout and their action failed to achieve any substantial support. They called it off on April 20, though over the next months there would be a number of individual strikes, as the prisoners continued to attempt to resistâor at least draw attention toâthe conditions of their incarceration.

7

Meanwhile, some prisoners' situations actually deteriorated, with the cases of Gabriele Rollnik,

8

Werner Hoppe, and Karl-Heinz Dellwo causing particular alarm.

With the exception of one month in Stammheim alongside other RAF prisoners,

9

Hoppe had spent the entire seven years since his arrest in isolation. By June 1978, he could not eat without vomiting, suffered from intestinal bleeding, had pain in his right shoulder, and could barely walk; he was finally transferred to Hamburg's Altona General Hospital in September. There, Professor Wilfried Rasch, director of the Institute for Forensic Psychiatry in Berlin, concluded that a return to prison, even under normal conditions, would endanger Hoppe's life, as would detention in a prison hospital. Even if released, full recovery was deemed unlikely.

10

As for Dellwo, he would later describe his situation at Cologne-Ossendorf as follows:

Between October 1977 and December 1978 I was also one of the prisoners who were mistreated in all sorts of ways as a revenge for the attacks of the guerilla: for months a guard was sitting in front of my cell, looking through the peep-hole every three minutes and writing down what I was doing. Occasionally they would bang at the door or shout insults or scornful remarks at me. For one year the light stayed on also throughout the night and if I made any attempt at darkening it the guards bursted (sic) in and usually carried me off to the “bunker” again. One little sign from the yard towards any other window was enough for the hour outside to be broken off by force.

Whatever could be removed from my cell they took away. My cell was ransacked every day, everything turned upside down, papers mixed up, messed up with food or just trampled down. There were days on which I was forced to undress completely and change all my clothes 10 times, each time I left my cell or returned to it.

11