The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History (55 page)

Read The Red Army Faction, a Documentary History Online

Authors: J Smith

Everything interested us, every approach that people on the outside found for organizing their resistance. We wanted to know: What are your disagreements with us? What do you mobilize around? How do you educate yourselves? What steps do you take and what experiences do you have as a result? It was difficult to say anything about this from inside prisonâwhich the people who wrote us often wanted us to do. For example, I had already been inside for ten years, which meant that the reality outside was completely foreign to me. That inclines a person to overestimate things and to be overly optimistic. However, this feeling of no longer being completely cut off meant a lot to me at the time. It creates a new strength and makes you more alive.

15

Möller attempted to take things further, and plans were made for some of these new correspondents to visit her. However, she found that, “Visits under these conditions don't lead to lasting relationships. At the time, I just couldn't write letters.” Suddenly she would find herself sitting in front of someone she had never seen before, and who was totally uncomfortable, not least because of the rigmarole visitors to political prisoners were put through. Only to meet separated by a glass partition with an LKA agent there all the time, taking notes about everything

said. As Möller experienced it, by the time people got over their discomfort, there would only be a few minutes left.

16

Furthermore, visitors from the anti-imperialist movement were often barred after two or three visits, on the grounds that they were not helping the “resocialization” process;

17

in some cases, activists were simply barred from visiting any political prisoners.

18

Nevertheless, it was an invaluable experience for her: “Not much remains as a result of itâbut at the time, it was a very important initiative for us.”

19

For two years, anti-imps had been busy discussing and implementing the May Paper. The RAF had not only acknowledged the importance of the semi-legal movement, it had charged it with building the still-abstract “front,” reaching out to the radical left. Following this lead, many now redoubled their efforts to work with the

Autonomen.

As they worked in uneasy tension with the anti-imps, the

Autonomen

were simultaneously finding themselves shunned within the peace movement which was bracing itself for the mobilization against the new NATO missiles being deployed that fall. Yet another Coordinating Committee had been established in April 1983, and while the more conservative actors failed to squelch plans for decentralized civil disobedience actions, they had no trouble pushing through the line that these should remain nonviolent, and that an “open relationship” with the state should be pursued.

20

The process of isolating and marginalizing radicals intensified, the demand for “nonviolence” in the face of nuclear war being intrinsic to this process. As detailed elsewhere:

Between 1980 and 1982, the radical anti-war movement was marginalized by many organizations and initiatives, including the DKP,

21

the Greens, the Jusos, and most pacifist and church groups. This allowed the peace movement to replace the antiwar movement. Church groups and social democrats became dominant and cemented their role by establishing a central coordination committee in Bonn. Some of these activists took their “leadership

role” and the demand to “keep the peace” so seriously that they collaborated with the police when it came to undermine the politics and tactics of the Autonomen.

22

This process crossed an important threshold on June 25, 1983, the day U.S. Vice President Bush Sr. visited Krefeld, in North Rhine-Westphalia, to commemorate the three-hundredth anniversary of the arrival of the town's first emigrants to the United States. Over twenty-five thousand people formed a human “wall of life” under the auspices of the official peace movement, while roughly a thousand

Autonomen

and anti-imps gathered separately in the town center.

23

Isolated in this way, the radicals were attacked by the SEK (similar to a North American SWAT unit); despite defending themselves with molotov cocktails and two by fours,

24

at least sixty of their number were badly injured and one hundred and thirty-four were arrested.

25

While a few hundred did manage to regroup to lob rocks and paint bombs at Bush's motorcade later that afternoon,

26

the day was considered a defeat. (As for the vice president, he gloated that “All this reminds me of Chicago in 1968. It makes me feel at home.”)

27

The reaction from the Coordinating Committee was to repudiate the

Autonomen

and anti-imps. In their words,

The peace movement declares clearly and bluntly, that its actions are carried through with solely non-violent means. Whoever uses violence, places himself outside the peace movement and is detrimental to its objectives⦠The police are not the opposition of the peace movement.

28

While certain groups objected that the CC did not have “the right to define who or what the peace movement is in this country,”

29

the radical left simply did not have the strength to push the movement against nuclear weapons to make a revolutionary break. At the same

time, Friedrich Zimmermann, the new minister of the interior, began turning the screw, drafting legislation to allow police to arrest anyone caught in the vicinity of “violent” protesters. Zimmermann's goal was twofold: to criminalize the broader opposition to the NATO missiles, and to push the conservative groups to move against the radicals. It was an effective strategy.

30

(Unsurprisingly, to ensure the trick worked, the

Verfassungsschutz

was more than happy to provide some of the “violent demonstrators” in question, and indeed, it was subsequently revealed that Peter Tröber, a “particularly violent” rioter who had traveled to Krefeld from West Berlin, was in fact a

Verfassungsschutz

agent taking orders from Lummer at the Berlin Ministry of the Interior.)

31

As Helmut Kohl's Conservative-Liberal coalition moved ahead with plans to welcome NATO's new medium-range missiles that fall, the

Autonomen

debated how or even whether to intervene. Some groups opted to continue working within the broader peace movement, upping the ante and pushing the envelope in the hopes of radicalizing others. But for many, the results were disappointing:

The peace movement with its strong nonviolent ideology continued to exclude all anti-imperialist and social-revolutionary forces. Their protestsâeager to prove their nonviolent commitmentâbecame predictable and empty symbolic gestures of submission to the state. The collaboration with the police also continued. Many peace activists not only wanted to control the Autonomen but were also willing to denounce them.

32

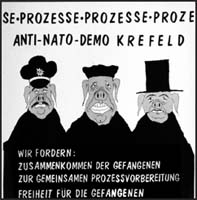

Autonomen and anti-imps demonstrating against Bush Sr. in Krefeld.

If the

Autonomen

had entered the peace movement with the goal of radicalizing it, the anti-imps had done so with the more modest hope of connecting with and winning over specific radical elementsânot least among them, the

Autonomen.

As such, the disappointment many people felt as they were ostracized by the movement leadership provided a new clarity, and while some were demoralized and demobilized, others found themselves drawn in a more militant direction. As usual, state repression was central to this process, as observed in this anti-imp statement from February 1983:

The situation is now clear: given the change of government and the possibility of the unopposed stationing of medium-range missiles, 1983 will be a “decisive year.”

It could be a year marked by the most powerful mobilization against the NATO strategy.

The state is fully prepared for that eventuality, and a reactionary offensive against the entire spectrum of the resistance has been going on for some time; the largest FRG-wide wave of trials since â45, with Helga [Roos'] trial at Stammheim being the cutting edge, as it is meant to serve as an example for the entire anti-imperialist political movement. In Spiegel

2/8

3 you can read about the technical level of BKA and Verfassungsschutz operationsâcertainly (and by definition) not just against the guerilla. The BAW increased its agitation against the resistance during the manhunt accompanying NATO maneuvers and with the three arrests. At his annual press conference, Rebmann announced that there would be more arrests of people from the anti-imperialist resistance. And now we have the terror against the prisoners. Helga is to be destroyed, because she wants to speak with Adelheid [Schulz].

33

This tried and true approach, building on opposition to state repression, was evident immediately following the anti-Bush demonstration, as unknown anti-imps firebombed the Wuppertal Justice Academy, sending “Love and Strength to Our Imprisoned Comrades from June 25 in Krefeld and All Other Imprisoned Militants”:

We decided to attack as quickly as possible in order to prevent the arrests and beatings carried out by SEK units from forcing us onto the defensive, and to avoid spending weeks debating what we could do about it, by instead striking back directly and not

letting up. For us, it is important to learn to constantly struggle against the fear that each of us feels and to embrace the reality that this individual fear can only be prevented from developing and can only be overcome through collective confrontation.

Even if every one of our people who is locked up represents a loss for us on the outside, they cannot prevent us from uniting through the walls and bars in common struggle with our imprisoned comrades, each of whom strengthens the struggle within the prisons. We see the struggle for the organization of the revolutionary prisoners, i.e., for the association of the prisoners from the RAF and the resistance in self-determined groups, as a significant part of the struggle against the NATO war policyâin this case, the attempt to use prisons to destroy the resistance and to frighten people collapses in the face of the prospect of collective struggle in the prisons. Those of us on the outside are responsible for bringing pressure to bear in support of association.

The Justice Academy is part of the prison system, as it trains the jailers to control and dominate prisoners. We see our attack against this counterinsurgency institution as part of organizing the revolutionary front that has developed out of the unity of the guerilla, the prisoners, and the militants.

34

“Krefeld Anti-NATO Demo Trial; We demand: Association for the prisoners to prepare a common defense; Freedom for the prisoners”

In this way, at the same time as they were being marginalized by the peace movement, militants could remain grounded through the legacy the guerilla and its supporters had built up over the years. As one speaker pointed out at a demonstration at the Krefeld courthouse in November 1983, “The Krefeld prisoners are not alone. They can draw on the experience from the years of prison struggles.”

35

As the anti-imps reached out to the

Autonomen,

the RAF was working to implement the ideas found in the May Paper, deepening its own relationships with supporters. In the midst of the constant arrests, both aboveground and underground, the group prepared for this vision of an intermediate level of resistance, a kind of anti-imp parallel to what the RZs had accomplished: the front.

On March 26, 1984, RAF members robbed a bank in the Bavarian town of Würzburg, netting 171,000

DM.

A few months later, on June 22, police in the town of Deizisau in Baden-Württemberg came upon a woman conducting surveillance of the home of Klaus Knopse, the judge who had been presiding over the trial of Mohnhaupt and Klar, which had started earlier that year. When she was asked for her ID, she pulled a gun and started shooting, but without hitting any of the police officers. Manuela Happe took off running, only to be arrested in a cornfield shortly thereafter.

36