The Reenchantment of the World (28 page)

Read The Reenchantment of the World Online

Authors: Morris Berman

of Modern Science," "it is the ultimate picture which an age forms of

the nature of its world that is its most fundamental possession. It is

the final controlling factor in all thinking whatever." In "Philosophy

in a New Key," Susanne Langer elaborates this theme by stating that

the crucial changes in philosophy are not changes in the answers to

traditional questions, but changes in the questions that are asked. "It

is the mode of handling problems, rather than what they are about, that

assigns them to an age." A new key in philosophy does not solve the old

questions; it

rejects

them. The generative ideas of the seventeenth

century, she says, notably the subject/object dichotomy of Descartes,

have served their term, and their paradoxes now clog our thinking. "If

we would have new knowledge," she concludes, "we must get us a whole

world of new questions."40

a new solution to the mind/body problem, or a new way of viewing the

subject/object relationship. We need to deny that such distinctions exist,

and once done, to formulate a new set of scientific questions based on a

new modality. When I studied physics in college, for example, a unit was

devoted to heat, then to light, then to electricity and magnetism, and

so on. The project involved in each unit, the "generative idea," was, in

effect, to ascertain the nature of light, heat, electromagnetism, etc. We

see in this curriculum the strong grip of the Cartesian paradigm. Fifty

years after the formulation of quantum mechanics, these subjects are

still taught as though there can be a knowledge of them independent

of a human observer. Again, I am not taking a Berkeleyian position:

whether these things exist independently of our observation of them

is not something I regard as a fruitful line of inquiry. What

is

at

issue is the notion that observation makes no difference for what we

learn about the thing being investigated. It is by now abundantly clear

that we are part of any experiment, that the act of investigation alters

the knowledge obtained, and that given this situation, any attempt to

know all of nature through a unit-by-unit analysis of its "components"

is very much a delusion. A question such as "What is light?" can have

only one answer in a post-Cartesian world: "That question has no meaning."

should

we ask? The reader is aware that I am not a scientist and am probably

the wrong person to try to answer these questions. But having started

this discussion, I am obliged to make some attempt to finish it,

hoping to provide some valuable suggestions that others might develop

further. Since I have already dealt extensively with the study of light,

let me continue to organize the discussion around this problem. My choice,

of course, is not arbitrary, for Newton's study of the nature of light

became the atomistic paradigm, the model of how all phenomena should be

examined. I am thus attempting to grasp, by working with an archetypal

example, what a sensual or holistic science might become; what it would

mean to acknowledge participation by deliberately including the knower

in the known.41

to show that a beam of white light was composed of seven monochromatic

rays, and that each color could be identified by a number, signifying

the degree of refrangibility. Today, the significant number is taken to

be wavelength or frequency, but the Newtonian definition of color as a

number is fully preserved. Red, for example, is the sensation caused by

such-and-such a wavelength of light in the eye of a standard observer.

the work of Edwin Land, the inventor of the Polaroid camera. Land was

able to demonstrate that colors were not simply a matter of wavelength,

but that their perception was largely dependent on the objects or images

that they represented; in short, on their context and its (human)

interpretation. A white vase bathed in blue light is seen as white

because the mind (Mind) accepts whatever the general illumination is, as

white. The same phenomenon can be seen in the case of yellow automobile

lights or candle flames, which are commonly perceived as white. Land

discovered that even two closely placed wavelengths of light, for

instance two different shades of red, can generate the full range of

color in the eye of the observer.

theory of light and color, Land was led to an explanation that echoed

the critique of Newton made by Goethe in his much-ridiculed book

"Farbenlehre" (On the Theory of Colors, 1810). "The answer," wrote Land,

"is that their work [i.e., the work of Newton and his followers] had very

little to do with color as we normally see it." (Goethe's phrase was:

"Derived phenomena should not be given first place.") In other words,

superimposed rays of monochromatic light are artificially isolated in

the laboratory, and although no one is denying their importance in (for

example) laser technology, they simply do not occur in nature. In his

own experiments, Land discovered that the characteristic arrangement of

colors was indeed a spectrum, but one that ranged from warm to cool --

something artists have known for centuries. "The important visual scale,"

he concluded, "is not the Newtonian spectrum. For all its beauty the

[Newtonian] spectrum is sunply the accidental consequence of arranging

stimuli in order of wavelength."

system of Newton's Europe deemed it sensible to identify colors with

numbers or to arrange them in order of wavelength. The perception of

colors in atomistic, quantifiable terms was made possible by Western

industrial culture and ultimately delivered back to this culture

technological devices, such as the sodium vapor lamp or the spectroscope,

that "verified" this perception in a beautifully circular way. More

significant here is the fact that Land's experiments demonstrate that the

Newtonian spectrum is

one way

of looking at light and color, but that

there is nothing holy about it. Furthermore, Land's conclusions reveal the

repression implicit in Newtonian science, even in this one special case,

for the talk of warm versus cool colors plunges us directly into affect,

and into human subjective interpretation. Degrees of refrangibility

are supposedly "out there," eternal, not requiring a human observer to

establish their validity. Hot and cold, however, are "in here" as well as

"out there"; they require a human

participant

, in particular, one with

a body and its accompanying emotions. Nor are degrees of refrangibility

very stimulating emotionally. The quantification of color represents

a dramatic narrowing of emotional response. The linguist Benjamin Lee

Whorf was fond of pointing out that eskimos have thirteen different words

for white, and certain African tribes up to ninety words for green. In

contrast, European languages collapse an entire range of emotion and

observation into three or four words: for example, green, blue-green,

aqua, turquoise. We begin to understand what Lao-tzu meant when he said,

"the five colors will blind a man's sight."

thing is that affect and analysis not be differentiated. If the experiment

does not include emotional/visceral responses, it is not scientific, and

therefore not meaningful. This approach does

not

rule out the Newtonian

color theory. The "validity" of the classical theory of color, however,

lies not in something inherent in nature, but in our appreciation and

enjoyment of it; and one can certainly enjoy lasers, spectroscopes,

and games with prisms. But if this theory is going to exhaust the

investigation of the subject, then it is unscientific by virtue of

omission. Land's work may thus be seen as the beginning of a paradigm for

the holistic investigation of light and color. In the same vein, research

on the psychology of color has demonstrated that a red rectangle does feel

warmer and larger than a blue one of equal size. Certain combinations of

colors make us feel sad, euphoric, dizzy, or claustrophobic. A number

of prisons in the United-States have recently installed a "pink room,"

incarceration in which for a mere fifteen minutes reduces the victim,

ŕ la "Clockwork Orange," to complete passivity.42 Phrases such as

"I feel blue" or "that makes me see red" are not just metaphors, and

an entire discipline, called "chromo-therapy" by its practitioners,

has grown up around the intuitive recognition that certain colors have

healing properties. We also now know that a field of colors, called an

"aura," surrounds every living thing, and that children perceive it up

to a certain age. It is likely that auras are still commonly perceived

in nonindustrial cultures, and probable that the yellow halos painted

around the heads of various saints in medieval art were something actually

seen, not (according to a modern formulation) a metaphor for holiness

"tacked on" for religious effect.

articulated paradigm, but I believe that the holistic exploration of such

inexhaustible subjects as color, heat, or electricity, will give us -- as

Susaune Langer urged -- a whole new world of questions. The key scientific

question must cease to be "What is light?," "What is electricity?," and

become instead, "What is the

human experience

of light?" "What is the

human experience

of electricity?" The point is not simplistically to

discard current knowledge of these subjects. Maxwell's equations and the

Newtonian spectrum are clearly part of the human experience. The point

is instead to recognize the error that arises when the human experience

is defined as that which occurs from the neck up -- the "Idol of the

Head," we might call it. It is the incompleteness of Cartesian science

which has made its interpretation of nature so inaccurate. "What is

the human experience of nature?" must become the rallying cry of a new

subject/object-ivity.43

not without its exciting aspects. At the very point that the mechanical

philosophy has played all its cards, and at which the Cartesian paradigm,

in its attempt to know everything, has ironically exhausted the very

mode of knowing which it represents, the door to a whole new world

and way of life is slowly swinging ajar. What is dissolving is not

the ego itself, but the ego-rigidity of the modern era, the "masculine

civilization" identified by Ariès, or what the poet Robert Bly calls

"father consciousness." We are witnessing the modification of this entity

by a reemergent "mother consciousness," the mimetic/erotic view of nature

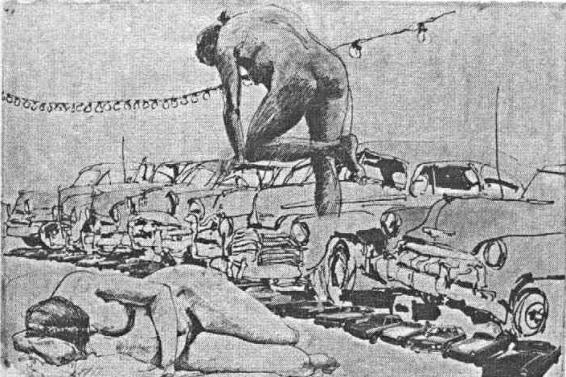

(see Plate 18). "I write of mother consciousness," states Bly in his

breathtaking essay, "I Came Out of the Mother Naked,"

other possibility for a man. A man's father consciousness cannot

be eradicated. If he tries that, he will lose everything. All he

can hope to do is to join his father consciousness and his mother

consciousness so as to experience what is beyond the father veil.

consciousness is good. But we know it is father consciousness saying

that; it insists on putting labels on things. They are both good. The

Greeks and the Jews were right to pull away from the Mother and drive

on into father consciousness; and their forward movement gave both

cultures a marvelous luminosity. But now the turn has come. . . . 44

Plate 18. Donald Brodeur, "Eros Regained" (1975). By permission of the artist.

the Greeks and the Jews as producing cultures of "marvelous luminosity,"

for in doing so he poses a caveat for all thorough-going Reichians. It

may well be that the culture of Europe from the Renaissance to the

present has been based on sensual repression; and Reich may well have

been right in believing (unlike Freud) that culture per se did not

have

to depend on repression; but whatever the energy that fueled it,

the brilliance of modern European culture is surely beyond doubt. The

whole of the Middle Ages did not produce a sculptor like Michelangelo,

a painter like Rembrandt, a writer like Shakespeare, or a scientist like

Galileo; and in terms of sheer volume of creativity, the comparison is

even more dramatic. Bly's crucial point, however, is that the "marvelous

luminosity" has reached its limits. It has become a hostile glare,

a scorching ball of fire that, as Dali tried to suggest, even melts

clocks in an arid desert landscape. Its most creative outposts are now

self-criticisms, analyses of the culture that double it back on itself;

quantum mechanics, surrealist art, the works of James Joyce, T.S. Eliot,

and Claude Lévi-Strauss. There is a chance, as Bly suggests, that a more

luminous culture "lies beyond the father veil," one that may warm and

nurture rather than burn and dessicate. Indeed, as an act of faith, I am

convinced of it. But for now, it is clear that the sharp subject/object

dualism of modern science, and the technological culture that religiously

adheres to it, are grounded in a developmental gone awry. Cartesian

dualism, and the science erected on its false premises, are by and large

the cognitive expression of a profound biopsychic disturbance. Carried to

their logical conclusion, they have finally come to represent the most

unecological and self-destructive culture and personality type that the

world has ever seen. The idea of mastery over, nature, and of economic

rationality, are but partial impulses in the human being which in modern

times have become organizers of the whole of human life.45 Regaining

our health, and developing a more accurate epistemology, is not a matter

of trying to destroy ego-consciousness, but rather, as Bly suggests, a

process that must involve a merger of mother and father consciousness,

or more precisely, of mimetic and cognitive knowing. It is for this

reason that I regard contemporary attempts to create a holistic science

as the great project, and the great drama, of the late twentieth century.

Other books

The Conspiracy Against the Human Race by Thomas Ligotti

Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradbury

Edge of Time (Langston Brothers Series) by Blue, Melissa Lynne

Scorch by Kaitlyn Davis

After the Fire: A True Story of Love and Survival by Robin Gaby Fisher

Succulent by Marie

Night's Favour by Parry, Richard

Goblin Precinct (Dragon Precinct) by DeCandido, Keith R. A.

Jasper Fforde_Thursday Next_05 by First Among Sequels

Winter's Kiss by Felicity Heaton