The Rescue of Belle and Sundance

Read The Rescue of Belle and Sundance Online

Authors: Birgit Stutz

Table of Contents

For my grandmother, Hedwig Greutmann,

who passed on to me her love for animals.

who passed on to me her love for animals.

And for Belle and Sundance.

“I hope you will fall into good hands; but a horse never knows who may buy him, or who may drive him; it is all a chance for us . . .”

—

Black Beauty

by Anna Sewell, 1877,

a wise mare’s advice to her foal

Black Beauty

by Anna Sewell, 1877,

a wise mare’s advice to her foal

“The greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.”

—Mahatma Gandhi, 1869–1948

Chapter 1

MOUNT RENSHAW

H

igh on the cold, stark mountain, the two horses waited patiently, as horses do.

igh on the cold, stark mountain, the two horses waited patiently, as horses do.

That fall, the sprawling meadows above the treeline had been resplendent with colour from wildflowers—the red of Indian paintbrush, the yellow of monkey flowers, the deep purple of tall gentians. Rushing creeks would have offered the horses bracing drafts of pure water, and the grass in the alpine meadows, though short, would have been rich and plentiful.

But when the temperatures began to plummet with winter’s approach, the grass was soon buried in white, buried beyond the

horses’ pawing, which turned frantic and then ceased altogether. The two horses, a young mare called Belle and a bigger, older gelding called Sundance, each a different shade of brown, stood amid six feet of powdery white snow. The conifers nearby all sagged under the great weight of accumulated snow and ice. Vainly seeking warmth from the other’s bony carcass, the two gaunt creatures arranged themselves nose to tail, though little remained of their tails—a sure sign they were starving. Each horse had gnawed away at the other’s tail, desperately looking for a source of protein.

horses’ pawing, which turned frantic and then ceased altogether. The two horses, a young mare called Belle and a bigger, older gelding called Sundance, each a different shade of brown, stood amid six feet of powdery white snow. The conifers nearby all sagged under the great weight of accumulated snow and ice. Vainly seeking warmth from the other’s bony carcass, the two gaunt creatures arranged themselves nose to tail, though little remained of their tails—a sure sign they were starving. Each horse had gnawed away at the other’s tail, desperately looking for a source of protein.

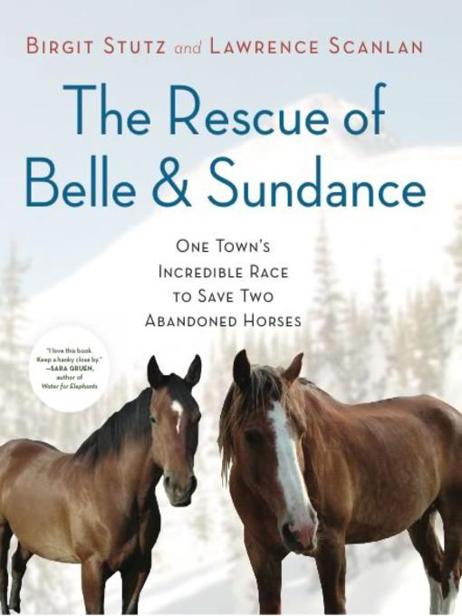

The alpine below Mount Renshaw, where Belle and Sundance were spotted by local snowmobilers.

The view from this mountaintop is one of unparalleled beauty, and it may be that horses, like humans, appreciate such grandeur. But not when the eyes stare blankly, the belly is long empty, the ribs and hip bones are plain to see.

A great many blizzards had already whipped through this section of the Rocky Mountains, and a cruel blanket of snow and ice lay on the horses’ backs. They were shivering and waiting for the inevitable.

The story of Belle and Sundance features a cast of many characters—some of whom played crucial roles in what happened next. For various reasons, I became one of the voices of the story that unfolded just before Christmas of 2008.

I was born in Zurich, Switzerland, in 1971. I spent the first two years of my life in Thalwil, a town near Zurich, but grew up in a village called Richterswil, on Lake Zurich. I have always loved animals and, at age thirteen, began taking riding lessons. I bought my first horse, Machlon, a somewhat crazed Russian–Arabian who had been abused and whom I still have, when I was in my early twenties. After high school, I studied English literature, English linguistics, journalism and North American history, but I always

harboured what I called “a cowboy dream”—to own a ranch and live in the mountains of Western Canada.

harboured what I called “a cowboy dream”—to own a ranch and live in the mountains of Western Canada.

I am now living that dream with my husband, Marc Lavigne. At our eighty-acre Falling Star Ranch near McBride in the Robson Valley of British Columbia, I train and breed horses—mostly part-bred Arabians—and teach riders.

What put me up on Mount Renshaw was simple. I cannot stand to see animals suffering, and it seems I am not alone.

McBride is a small town in the wide, flat valley near Mount Renshaw in northeastern B.C. Just a century ago, most men in the valley made their living as trappers and loggers, and their families lived in log cabins. Sawmills sprouted up to meet the demands of the new railroad that came through in 1912. Timber was needed not only for the Grand Trunk Pacific’s rail ties but also for sidewalks, fences, houses and stores in the villages that would dot the rail line. Tête Jaune Cache. Valemount. Dunster. Dome Creek. Crescent Spur. Croydon. Lamming Mills. And the biggest, McBride, named after a British Columbia premier of the early twentieth century and today home to seven hundred souls. All of these towns’ names are rooted in the rich pioneer history of the Robson Valley. Tête

Jaune, meaning Yellow Head, remembers the long blond hair of a local Métis guide who crossed the Rocky Mountains in 1819 in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Mount Renshaw is named for a trapper who worked out of McBride in the early 1900s.

Jaune, meaning Yellow Head, remembers the long blond hair of a local Métis guide who crossed the Rocky Mountains in 1819 in the service of the Hudson’s Bay Company. Mount Renshaw is named for a trapper who worked out of McBride in the early 1900s.

The valley sits on the edge of an interior cedar–hemlock rainforest, the world’s only inland temperate rainforest—one that thrives thanks to the west winds that bring ample rain in summer and snow in winter to fuel forest growth. Some of the trees around McBride are more than a thousand years old. The forest, with the help of sturdy horses, has long offered a living here—though never an easy one. Loggers felled the giant Douglas firs and cedars and hemlocks in winter, horses hauled the logs to the mills, millworkers cut them into lumber, and the trains took it all away. For a century, that’s what made the valley tick.

But the mills’ day had come and, just recently, all but gone. Decisions made in capitals and corporate boardrooms far to the east, limp demand for building material in the wake of a real estate crash to the south, bank failures there and pinched pockets everywhere have all rocked the valley. Jobs in the forests around McBride have become scarce. Tourism, for better or for worse, has taken over. Hikers and horseback riders, hunters and fishers, kayakers and whitewater rafters, mountain bikers and birdwatchers find a haven here in summer. In winter, heli-skiers, cross-country skiers and

recreational snowmobilers find the area irresistible. The air is pure, the waters pristine, the sense of space and freedom keenly felt.

recreational snowmobilers find the area irresistible. The air is pure, the waters pristine, the sense of space and freedom keenly felt.

“We live in beauty,” a friend of mine once told me, and there are takers in every season, winter most of all.

Other books

Dates on My Fingers: An Iraqi Novel (Modern Arabic Literature) by Muhsin al-Ramli

Madness by Kate Richards

Murder in Lascaux by Betsy Draine

Emma’s Secret by Barbara Taylor Bradford

Fire with Fire (Demonblood Series #2) by Penelope King

Showdown in Mudbug by Jana DeLeon

To Surrender to a Rogue by Cara Elliott

Now I Know by Aidan Chambers

PlaybyPlay by Nadia Aidan