The Rich Are with You Always (51 page)

Read The Rich Are with You Always Online

Authors: Malcolm Macdonald

Over all that blighted land lay the cloying stench of decaying potatoes. The earth looked as if a wet fire had passed over it. Everywhere, they saw families digging desperately among the wilted plants, seeking a few tubers they might salvage. Several times John stopped the coach and got out to see the blight for himself; it was as if he could not believe the vastness of it and had to remind himself, time and again, of its horror. In all that sombre day they did not see one potato plant left green, nor one potato tuber that would not crush to an evil black slime at the slightest pressure.

The faces of those who alighted from the "celebration" train from Dublin next day told the rest of the story. They too had come through mile after mile of black field upon black field. The day was so wintry that the green upon the trees and hedgerows seemed incongruous. Fierce and heavy downpours of cold rain swept down from the Wicklow mountains, drenching the land. Lightning flickered over the wasted fields. And toward evening a dense, chill mist sprang up, seemingly out of the ground, and enveloped them all. The Carlow branch had a very muted opening.

Over the days that followed their return to Dublin, the reports from all parts of the country made it clear that the potato failure had been total. Not a parish had been spared.

The anguish of the people was now universal. For months the relief works had kept a bare sufficiency of flesh on their bones; but the hopes that survived with it had all been pinned on the coming bounteous harvest of potatoes. Overnight the crop and those hopes had turned to the colour of despair. Everything that could be pawned had already gone. Every debt they could incur, they had already incurred. Every last scrap of food they could find they had long since devoured. They faced the winter with nothing. From the far west, where the deepest poverty lay, the most piteous tales were arriving. Naval boats put ashore where every shellfish had been pried from the rocks and every last strand of seaweed been eaten; there they found whole villages of skeletons, some still with flesh upon them, a few still actually breathing.

When John realized the magnitude of the disaster, he was tempted to the same despair as had seized the rest of the country. What could one do? The government, encouraged by the prospect of a good harvest, had closed down all relief, had ordered no new supplies of grain to fill commissariat depots that were now empty, and had voted no new money for public works. The European harvest in general was, as Rodie had said back in June, deplorable; prices were already high and the English labourer was feeling the pinch. If the government now went into the market for grain for a starving Ireland, the price would hit the moon and there would be bread riots at home. It was too late. Hundreds of thousands were going to die and all the money in the exchequer could not save them. What could one do?

"We can take away no profit from these Irish contracts, love," he said to Nora.

He expected her opposition but she agreed at once. "The question is," she said, "what do we do with it? Where do we apply it? It will be tens of thousands of pounds. We must not waste it merely to make ourselves feel good."

She herself was surprised at her agreement. It made her wish they had not come to Ireland. When you saw the misery of so many people and sensed the terrible fear that gripped them, it was hard to think properly and make calm decisions. She hated mixing money and emotion; no good ever came of it. Unreasonably—knowing it to be unreasonable—she turned her annoyance upon John.

"I have no idea what to do yet," he said, unaware of her mood, glad only that she agreed—or appeared to agree. "We must think hard and consult with many people. Certainly it would be folly for us to try anything on our own. The desperation that swamps every government effort would annihilate us entirely."

"And meanwhile," she said, "we have forty-three other contracts, great and small, to tend. And fifty to sixty thousand mouths dependent on those efforts."

Their intended return to England was delayed twenty-four hours by the arrival of an urgent message from Lord George Bentinck, saying he was coming to Dublin and particularly asking John to stay and meet with him and advise him on the drafting of a bill requiring the government to support Irish railways.

Bentinck was a strange figure in English politics. The third son of the Duke of Portland, he was now forty-four, having sat in Parliament as member for Lyme Regis for the last twenty years. His love of racing—which he had purged of much corruption—and of field sports had led him to decline several ministries, yet he had had greater influence on Parliament than most who held high office. His liberal opinions on Catholic emancipation and the Reform Bill had led him out of the liberal camp into the Tory, where he had been one of Peel's staunchest supporters. Yet when Peel went over to free trade, Lord George Bentinck had led the protectionist wing of the Tories against him on that crucial defeat over the Irish Coercion Bill. There were many who said he would one day be a great prime minister. Young Disraeli worshipped him.

He and John met in Dublin Castle. Nora had come along too, intending to write some letters. But Bentinck had brought with him the proof slips of John's evidence to the select committee on railway labour; he said he had come upon them by chance at the government printers and, in reading them, had become aware of the true calibre of John Stevenson. "You are just the sort of person, sir, to advise me on this legislation I am preparing. I would deem your help a kindness and an honour."

Nora had borrowed the slips to look at while they conferred in another room. She read:

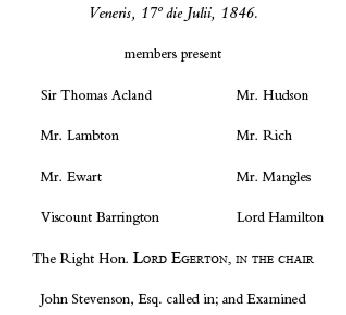

3174. Chairman.

] You are a railway contractor at present residing in Yorkshire?—I am.

] You are a railway contractor at present residing in Yorkshire?—I am.

3175.

And how long have you held that business?—I have been in the business of building railways for twelve years, eight of them as contractor. I began as a navvy and worked up to it.

And how long have you held that business?—I have been in the business of building railways for twelve years, eight of them as contractor. I began as a navvy and worked up to it.

3176. Sir Thomas Acland.

] Do many do that?—Not many stay. I have known one man who had contracts for 50,000

l

in 1841 who was

] Do many do that?—Not many stay. I have known one man who had contracts for 50,000

l

in 1841 who was

reduced again to a ganger in 1843.

3177.

How have you avoided that fate?—By carefulness. Careful estimating before the work, careful accounting on it, and careful use of the subsequent profit. And careful use of men.

How have you avoided that fate?—By carefulness. Careful estimating before the work, careful accounting on it, and careful use of the subsequent profit. And careful use of men.

3178. Chairman.

] How many men do you now employ?—A little more than 19,000. Most are directly contracted to me, about 17,000; but some are subcontracted.

] How many men do you now employ?—A little more than 19,000. Most are directly contracted to me, about 17,000; but some are subcontracted.

3179.

So you are as big as Mr. Peto?—Taller by nine inches, I believe. (Laughter) (Order) I apologize, sir. We are much of a muchness in size, as firms.

So you are as big as Mr. Peto?—Taller by nine inches, I believe. (Laughter) (Order) I apologize, sir. We are much of a muchness in size, as firms.

3180.

You have heard his evidence. He has described a method for dividing a contract among deputies, agents, overseers, timekeepers, and gangers that sounds for all the world like colonels, captains, subalterns, and sergeants in other clothing. Does your practise accord with his?—In effect it does. It accords on almost every detail in practise; though Mr. Peto and I are sharply divided in precept. In practise we both understand that a master with so many thousand men would soon go bankrupt if he failed to exercise that sort of military authority over them. In Mr. Peto's view that is absolutely right. His is an autocratic character. I do not mean that critically. He is a most benevolent autocrat and greatly respected by his men. But I look forward to a time when men accept the discipline of the working as a carpenter accepts the discipline of the grain of wood—of their own free will and understanding. So I do nothing to hinder the growth of self-reliance and self-discipline, even at the cost of actual discipline when my trust proves premature. I may say I am greatly hindered by the presence of the poorer and more ruffianly sort of contractor on adjacent workings. They encourage every sort of bad habit and low behaviour as well as low standards of work.

You have heard his evidence. He has described a method for dividing a contract among deputies, agents, overseers, timekeepers, and gangers that sounds for all the world like colonels, captains, subalterns, and sergeants in other clothing. Does your practise accord with his?—In effect it does. It accords on almost every detail in practise; though Mr. Peto and I are sharply divided in precept. In practise we both understand that a master with so many thousand men would soon go bankrupt if he failed to exercise that sort of military authority over them. In Mr. Peto's view that is absolutely right. His is an autocratic character. I do not mean that critically. He is a most benevolent autocrat and greatly respected by his men. But I look forward to a time when men accept the discipline of the working as a carpenter accepts the discipline of the grain of wood—of their own free will and understanding. So I do nothing to hinder the growth of self-reliance and self-discipline, even at the cost of actual discipline when my trust proves premature. I may say I am greatly hindered by the presence of the poorer and more ruffianly sort of contractor on adjacent workings. They encourage every sort of bad habit and low behaviour as well as low standards of work.

3181. Mr. Lambton.

] Some witnesses claim the quality of workman has greatly improved lately.—It has, taken since 1835. But it is too slow for me. The tramp-navvy has almost disappeared. I think it wrong to blame the workman though. A contractor who cheats his men, paying at two-month intervals and giving endless subscriptions meanwhile in truck, forcing poor beer and scrawny beef on them in place of coin of the realm, such a master reduces his workmen to despair and makes them terrors to the countryside.

] Some witnesses claim the quality of workman has greatly improved lately.—It has, taken since 1835. But it is too slow for me. The tramp-navvy has almost disappeared. I think it wrong to blame the workman though. A contractor who cheats his men, paying at two-month intervals and giving endless subscriptions meanwhile in truck, forcing poor beer and scrawny beef on them in place of coin of the realm, such a master reduces his workmen to despair and makes them terrors to the countryside.

3182. Mr. Ewart.

] And a burden on the parishes.—Yes. I have had such men come to me, who, when paid regularly, properly victualled, and fittingly housed, have turned into model labourers and even become smallish capitalists on their own account. It has often amazed me that the most dangerous ruffian under one system of employment becomes the chief ornament of the other system.

] And a burden on the parishes.—Yes. I have had such men come to me, who, when paid regularly, properly victualled, and fittingly housed, have turned into model labourers and even become smallish capitalists on their own account. It has often amazed me that the most dangerous ruffian under one system of employment becomes the chief ornament of the other system.

3183. Mr. Lambton.

] Of your system?—Yes.

] Of your system?—Yes.

3184. Chairman.

] Which is also Peto's system.—Not in every detail.

] Which is also Peto's system.—Not in every detail.

3185.

Where then do you differ?—I have tommy shops on all my larger workings. I heard a porkbutcher once claim he had made 5,000

l

profit in one year from navvy trade. That was before I was a contractor. I determined then, if ever it was in my power, I'd have none of it. My tommy man is the guarantee of it. But the labourer's liberty to buy where he will is also the guarantee that my tommy man does not replace one evil by another. There is a great and abiding sense of fairness in every Englishman which comes to the fore if you can only clip his avarice. (Laughter) By controlling the tommy man, I also control—indeed prevent—the sale of intoxicants at a working. It is a point that has not been sufficiently appreciated at this committee, at these inquiries. May I explain? It may happen that several gangs are working in a cutting, say a hundred men. The method is to work with three sets of wagons: one set filling, one set going to be tipped, and one set being tipped and returned. Each man among that hundred has his proper task. Now I have seen it come on to rain at ten o'clock and all the men take shelter. Some contractors let their gangers manage beer supplies at the working, and if the men have worked three hours, they will know they can call on the ganger for at least nine pence—which they may then settle to consume in beer. After six or seven pints, many will not resume work but will sit about under the hedges and sing and fight all day. Six men behaving in that way can so disorder the regular flow of the sets of wagons that the value of work done at the cutting is halved for that day. I have seen that more than once.

Where then do you differ?—I have tommy shops on all my larger workings. I heard a porkbutcher once claim he had made 5,000

l

profit in one year from navvy trade. That was before I was a contractor. I determined then, if ever it was in my power, I'd have none of it. My tommy man is the guarantee of it. But the labourer's liberty to buy where he will is also the guarantee that my tommy man does not replace one evil by another. There is a great and abiding sense of fairness in every Englishman which comes to the fore if you can only clip his avarice. (Laughter) By controlling the tommy man, I also control—indeed prevent—the sale of intoxicants at a working. It is a point that has not been sufficiently appreciated at this committee, at these inquiries. May I explain? It may happen that several gangs are working in a cutting, say a hundred men. The method is to work with three sets of wagons: one set filling, one set going to be tipped, and one set being tipped and returned. Each man among that hundred has his proper task. Now I have seen it come on to rain at ten o'clock and all the men take shelter. Some contractors let their gangers manage beer supplies at the working, and if the men have worked three hours, they will know they can call on the ganger for at least nine pence—which they may then settle to consume in beer. After six or seven pints, many will not resume work but will sit about under the hedges and sing and fight all day. Six men behaving in that way can so disorder the regular flow of the sets of wagons that the value of work done at the cutting is halved for that day. I have seen that more than once.

3186. Mr. Mangles.

] Do you think the safety of the railway labourer is adequately provided for?

] Do you think the safety of the railway labourer is adequately provided for?

Lord Hamilton

(intervening): There was a large difference of opinion there between Mr. Peto and Mr. Brunel.—I think, with respect, my lord, you are misreading Mr. Brunel. His evidence has been wrongly taken to indicate that most railway companies would deprecate the introduction of liabilities on the French system. In France, as you know, the companies are responsible for the support of men injured, for the support of widows and orphans of men killed, and for injury or damage to third parties or property, regardless of any question of actual blame or negligence. But he was concerned to point out that there are circumstances where to put absolute liability on the company would compel the directors to interfere with day-to-day working much to its detriment. And there I agree. There are certain independent labourers, among them being miners, whose self-reliance would be greatly diminished by that degree of interference.

(intervening): There was a large difference of opinion there between Mr. Peto and Mr. Brunel.—I think, with respect, my lord, you are misreading Mr. Brunel. His evidence has been wrongly taken to indicate that most railway companies would deprecate the introduction of liabilities on the French system. In France, as you know, the companies are responsible for the support of men injured, for the support of widows and orphans of men killed, and for injury or damage to third parties or property, regardless of any question of actual blame or negligence. But he was concerned to point out that there are circumstances where to put absolute liability on the company would compel the directors to interfere with day-to-day working much to its detriment. And there I agree. There are certain independent labourers, among them being miners, whose self-reliance would be greatly diminished by that degree of interference.

3187. Mr. Mangles.

] Can you exemplify that? We have no experience of the conditions you refer to.—You may imagine a miner who has contracted with me—that he and a mate or two mates will remove so many yards of face for such and such a fee within so many days. If I, or the company, were to be liable to him or his dependents, we should be ever about his ears, saying, you must use more shoring, you must use better timber, you must not undercut so high a face…and so forth. His independence would go.

] Can you exemplify that? We have no experience of the conditions you refer to.—You may imagine a miner who has contracted with me—that he and a mate or two mates will remove so many yards of face for such and such a fee within so many days. If I, or the company, were to be liable to him or his dependents, we should be ever about his ears, saying, you must use more shoring, you must use better timber, you must not undercut so high a face…and so forth. His independence would go.

Other books

Until Noon by Desiree Holt, Cerise DeLand

La vida instrucciones de uso by Georges Perec

The HOPE of SPRING by WANDA E. BRUNSTETTER

Aphrodite's Hunt by Blackstream, Jennifer

Elven Magic: Book 1,2, 3 by Chay, Daniel

Bound by Pleasure by Lacey Wolfe

Petrodor: A Trial of Blood and Steel, Book 2 by Shepherd, Joel

Micah's Island by Copell, Shari

Kinflicks by Lisa Alther

The Blessing by Nancy Mitford